Does turmeric really help protect us from cancer?

It’s a spice that’s been used in South Asian cooking for thousands of years, but can turmeric do more than flavour our curry – could it boost our health and even help prevent cancer?

Turmeric is a rather unassuming root that you’d easily overlook – but ground down it’s a yellow-orange spice that’s at the heart of just about every Indian curry. But over the years numerous articles have appeared claiming that this common spice is able to cure anything from heartburn to an upset stomach, and keep at bay serious diseases like diabetes, depression, Alzheimer’s, and even cancer.

There are thousands of studies published on turmeric, and in particular one compound thought responsible for many of the supposed health benefits: curcumin.

Trials on rats have shown that extremely high doses of curcumin managed to inhibit the development of several types of cancer, but only about 2-3% of turmeric powder is curcumin, and when we eat it, not much of that curcumin is even absorbed into our body. In the literature, though, there is a real dearth of studies on ‘normal’ dietary levels of turmeric (there’s not enough money in selling normal turmeric powder to make anyone want to invest the cash to fund the studies).

So, does a regular diet of modest amounts of turmeric give us any health benefits or should we be taking supplements packed with turmeric or curcumin to ward off disease?

We set out to find out, searching for teams all over the UK whose research could help shed light on the issue.

First port of call was Newcastle University who took blood samples from the volunteers and performed an ‘oxidative stress test’ developed by Dr Georg Lietz and his team. Then it was down to Leeds, where not one, but two state of the art labs were involved, one under the supervision of Dr. Mike Bosomworth at the Leeds General Infirmary and the other under the watchful eye of Dr Clive Carter in the Transplant and Cellular Immunology Lab at St James’ Hospital. The analysis in these two labs in Leeds was vital for the next stage of the plan, which was to send samples finally to Professor Martin Widschwendter and the team in at University College London for DNA testing.

The experiment

We teamed up with Newcastle University to run the experiment, and recruited nearly 100 volunteers. We took blood samples at the start of the experiment, and then they were split into three groups:

- The first group took 1 teaspoon of turmeric powder daily,

- The second group took the same amount of turmeric as a supplement

- The third group took a placebo pill.

For 6 weeks they’d follow this routine, and then we took blood samples again.

We did three tests on their blood samples:-

The first was developed by PB Biosciences at Newcastle, and it’s an “oxidative stress test”. It’s an exciting new test that measures how well participants’ blood cells resist inflammation, and gives an indication of how healthy their immune systems are. This would help assess whether turmeric might reduce inflammation enough to have an impact on chronic diseases like diabetes.

The second round of tests was a detailed count of their white blood cells. The results were required for UCL's DNA tests but this analysis also provided us with an indication of the health of their immune systems. Both teaching hospitals in Leeds were involved at this stage, Leeds General Infirmary and St James’ Hospital.

The final test we used was developed at University College London, and it involved looking at the methylation of their DNA. DNA carries the genetic code for all of our cells – but different cells ‘read’ different parts of the code. Methylation of the DNA prevents some parts of the code from being ‘read’ in different cells, so that they all get their own parts of the instruction. However, recent research has shown that methylation of the DNA can ‘go wrong’ and this can cause cells to become cancerous. At UCL, Professor Martin Widschwendter and his team have already shown a promising ability to predict breast and ovarian cancer long before it actually develops through spotting signature DNA methylation changes. We hoped to see changing methylation patterns that might indicate our volunteers’ bodies switching on and off different genes that might be related to diseases, including cancer.

The results

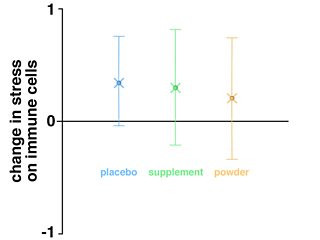

The oxidative stress test in Newcastle showed that there was a small increase in oxidative stress in all three groups equally.

Our immune systems are affected by seasonal changes – sunburn can increase oxidative stress on them, and it could be that over the 6 weeks this sort of change was happening to volunteers in all three groups.

Because the placebo group changed as much as the two turmeric groups we cannot attribute any change to the turmeric.

The white blood cell count also showed that in all three groups, the number of their immune cells had decreased, equally across the groups.

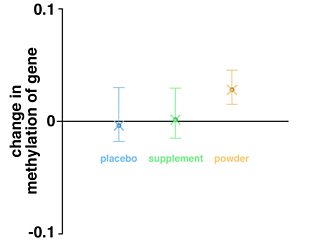

However, the DNA methylation test we did showed VERY exciting results.

There was no difference in the methylation of the DNA of our volunteers who took the placebo pills, or those who took the supplement pills, but there was a very significant change in the methylation patterns in the group who were cooking with turmeric powder.

On one gene in particular, the researchers at UCL saw a dramatic change, and this gene (known as SLC6A15) is associated with risks of depression and anxiety, asthma and eczema, and cancer.

The activity of the SLC6A15 gene was being changed.

It’s too early to tell whether the impact is a positive or negative one – but given that turmeric has been associated with improving these conditions, it is likely that these changes are beneficial.

There is one caveat to these conclusions – the researchers have not yet analysed the volunteers’ blood samples to determine the levels of curcumin (or other turmeric-related compounds) in it.

It could be that those cooking with the turmeric powder also changed their diet in a way that caused this methylation change and that it wasn’t the effect of the turmeric.

Measuring their blood levels of curcumin and comparing that with the levels of those in the supplement group (who did not see the DNA methylation change) would help make the link between turmeric/curcumin and the DNA methylation change.

Why would cooking with turmeric be different from taking it as a supplement?

It is thought that cooking with turmeric has an impact on how much curcumin from it our bodies are able to absorb. Curcumin is lipophilic, which means it binds to fats, and so when we cook with oils the curcumin binds to the oil and is more easily absorbed by our guts. Black pepper – more specifically, a compound of black pepper called piperine – might do the same thing, helping to smuggle even more of the curcumin into our bodies. Hence cooking with turmeric, black pepper and oils together might be a better combination.

What this means

This is an enormously exciting result – for us and the UCL lab – because it might be that we’ve found the mechanism by which turmeric provides us with health benefits – by affecting the behaviour of our very genes. It’s early days, but it’s worthy of further research.

For Professor Widschwendter it’s exciting because he’s interested in using his technique to develop strategies that we might use in order to prevent cancer long before it develops – and this result shows him both that his technique can track small changes over short periods of time, AND that turmeric might be worthy of further study as a substance that can help inhibit cancer development.

It’s very difficult to find ways to reduce the risks of diseases that take a long time to develop – such as cancer (or heart disease), and so tests that accurately give an ‘early warning’ of these diseases, and which are sensitive enough to show a subtle change in risk, are very valuable indeed (see ).

The results also suggest that eating small amounts of turmeric regularly may have a positive impact on your health.

It IS early days, but it may well be that this modest spice could help protect us from a range of chronic diseases.

Which, if you needed it, is a good excuse to have a curry!

Related Links

-

![]()

Bold health claims have been made for the power of turmeric. Is there anything in them, asks Michael Mosley.