Could viruses called bacteriophages be the answer to the antibiotic crisis?

Surgeon Gabriel Weston visited the Eliava Institute in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia to find out more about a decades-old treatment that could prove vital in the battle against drug resistant superbugs.

Our generation has been lucky enough to live through a golden age in medicine – the age of antibiotics, where drugs to kill bacterial infections off quickly are readily available. Now, though, growing numbers of bacteria are becoming resistant to our most powerful drugs, evolving into new strains – often called ‘superbugs’ – that we can no longer kill. Already drug resistance kills over 700,000 people globally every year and if we fail to tackle the problem it could cause an extra 10 million deaths a year by 2050.

New antibiotic drugs are proving difficult to find – but there is a completely different approach to killing bacteria that may prove vital in saving us from infections: using viruses.

‘Phage therapy’ uses naturally occurring viruses called bacteriophages (from the Greek meaning ‘bacteria-eaters’) to fight bacteria. The phages used in this therapy are harmless to people but lethal to bacteria. When a phage encounters its prey, it latches onto the outside and injects its own DNA inside the cell. This reproduces inside the bacterium and then the ‘daughter phages’ burst through the cell walls, before latching onto more bacteria and repeating the cycle until all the bacteria have been killed – and the infection has been dealt with.

Phages were first discovered by two different scientists – the Briton Frederick Twort in 1915 and the French-Canadian Felix d’Herelle in 1917, but it was d’Herelle who really pioneered phage therapy. For a while it was pursued in the west, but when antibiotics were discovered and came into common use in the 1940s phage therapy was abandoned and quickly forgotten.

Behind the iron curtain however, in Stalin’s Soviet Republic, access to antibiotics was limited, so phage therapy continued and a phage therapy centre was founded in Tbilisi, Georgia, by a scientist named George Eliava. Tragically Eliava was killed in 1937 during Stalin’s purges, but not before he had made Tbilisi a leading centre for phage research.

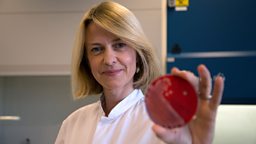

One of the most fascinating areas of the Eliava Institute are the phage laboratories where different phages are identified and developed into treatments for a vast range of infections. Unlike antibiotics, which target a broad range of bacteria, each phage kills only one type or strain, so doctors here begin by taking bacterial samples from patients and finding a phage from the lab that can kill that particular bacteria.

One of the great advantages with this therapy is that it’s much harder for bacteria to develop resistance to phages due to their diversity, their ability to evolve and their sheer abundance. Bacteriophages are actually the most abundant life form on earth – there are far more phages than there are stars in the visible universe. So if bacteria evolve to resist a particular phage, the scientists at the Eliava simply turn to their extensive phage library, or to nature, to find another. They also create what are known as ‘phage cocktails’ – mixtures of different phages that attack bacteria from different angles and make it much more difficult for them to develop resistance.

Currently phage therapy is not approved or regulated in the west and this is the next big challenge. The good news is that the first large scale, western standard clinical trials have now begun, so hopefully in future we see this incredible 100 year old therapy returning to Europe to help us beat the superbugs.