Which type of exercise gives you the strongest bones?

It is well known that exercise is good for the heart, lungs and brain. But there is one part of our body that is often overlooked: our bones.

As we get older, our bones become less dense, which can ultimately lead to them becoming weak and more prone to fractures. From the age of around 35 we lose approximately 0.5% of bone mass per year. This accelerates once women reach menopause, and for men, after the age of around 50 years.

Although calcium and vitamin D are well known to be essential for healthy bones, studies have shown that exercise can slow, or even reverse, the decline in bone strength with age.

It is believed that exercise helps to keep our bones strong by putting them under stress and subjecting them to jolts and shocks. Each jolt is thought to send signals to bone cells that trigger them to grow back stronger. Bone also responds directly to the local muscle, which, if well-developed, gives additional bone-building benefits.

But what is the best type of exercise you can do, to strengthen your bones?

The Experiment

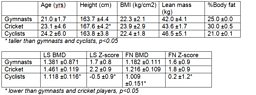

To find out, we teamed up with Dr Karen Hind, an expert in bone health at Leeds Beckett University. We and the Leeds team recruited elite male and female athletes – including Olympic medallists – from three different sports:

- Gymnastics

- Cricket

- Cycling

Studying these elite athletes allowed us to distinctly characterise bone density that may reflect the particular movements involved in different types of exercise.

This gave us an indication of what kind of exercises might benefit bone strength in the wider population and so might help avoid fractures in later life.

Each of our groups was analysed with a low radiation imaging method called a DEXA scan. This was used to measure the bone density in the athletes’ hips and spine, two common and serious problem areas for fractures in older people. The results were compared with the average bone density for people of the participants’ age and gender.

Women

Men

Conclusions

Whilst it was expected that gymnasts might have stronger bones than average, our results for cyclists and cricketers were surprising. Cyclists had less dense bones at the spine and hips than average, and cricketers had the densest bones of the three groups we tested.

These results suggest that the type of activity may be responsible for the differences we observed.

Gymnasts sustain repeated impacts due to jumping and landing, which is known to result in bone strengthening.

Cyclists’ weight is supported by their bikes, so it may be that they do not put sufficient pressure on their bones to strengthen them, particularly in the lumbar spine region. So while cycling is a good way to improve your fitness and cardiovascular health, our tests indicate it is not good for your bones.

Cricketers gave the most surprising result, having the densest bones in our tests. Although there is a popular perception of cricketers standing still most of the time, our results suggest that their brief moments of explosive activity (running, jumping and twisting) are beneficial to bone density. Muscle mass was also very well developed in the cricketers, especially in the male cricketers, and this was also positively associated with bone density.

This study gives a good indication what kinds of exercise we could all do to improve our bone health. Exercises that involve some jumping and twisting, such as dancing or star jumps, are likely to be beneficial.