Is coconut oil good or bad for your cholesterol?

The latest so-called ‘superfood’ whose sales are rocketing because of its health claims is coconut oil.

We spend around £16 million a year on it in the UK, some 70 times more than just 6 years ago.

Perhaps the most surprising claim is that eating coconut oil can cut your risk of heart disease by reducing your cholesterol levels.

Coconut oil is more than 80% saturated fat, which has long been associated with raising cholesterol levels.

And there are some reports suggesting that coconut oil does this, too, in line with expectations.

However, other reports claim that coconut oil is good for your heart, because it reduces levels of the harmful form of cholesterol, LDL.

How to measure changes in cholesterol

There are 2 different types of cholesterol which have opposite health implications.

LDL cholesterol is so-called ‘bad’ cholesterol, linked with increased risk of heart disease and stroke.

HDL cholesterol is ‘good’ cholesterol, thought to be beneficial because it carries away LDL from the blood stream.

Conventional scientific thinking would suggest coconut oil is bad for health because it is rich in saturated fat, and evidence suggests that saturated fat raises LDL levels.

Therefore, the health claims that coconut oil is good for your heart run counter to the body of scientific evidence. However, it is now marketed on a large scale, and its health effects in a British population are untested.

So is coconut oil good, or bad, for cholesterol? Trust Me I’m a Doctor wanted to find out.

The Experiment

We teamed up with Prof Kay-Tee Khaw and Prof Nita Forouhi from the University of Cambridge, to run a ground-breaking experiment.

We recruited nearly 100 volunteers, all over 50 years of age, to test what effect eating coconut oil would have on their cholesterol, compared to other fats.

We split our volunteers into three groups, who each added one of three fats to their diets every day for four weeks:

Group 1 had 50 grams of coconut oil a day, around two table spoons.

Group 2 had 50 grams of olive oil a day. This is an unsaturated fat already known to lower harmful ‘bad’ cholesterol.

Group 3 ate 50 grams of butter a day. Like coconut oil, butter is high in saturated fat.

Before our volunteers started their regime, their baseline levels of both types of cholesterol in their blood — the ‘bad’ LDL and ‘good’ HDL – were measured. These measurements were repeated at the end of the study.

The Results

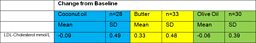

For LDL cholesterol, associated with an increased risk of heart disease:

For butter, study participants had an average increase in LDL cholesterol by 0.3 millimoles per litre, representing a rise of around 10%. The increased risk to heart health reverted back again once the regime was stopped.

For olive oil, there was a very small average reduction which was not statistically significant. This means there was essentially no difference in LDL cholesterol with participants on the olive oil diet.

For coconut oil, LDL cholesterol decreased by 0.09 millimoles per litre. This was also not statistically significant, so overall the results show there was no increase in LDL cholesterol for the coconut oil group.

Table 1: Change in LDL (‘bad’) cholesterol

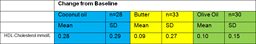

We also measured HDL, so-called ‘good’ cholesterol. Butter and olive oil both raised HDL by about 5%, but coconut oil raised it by around 15%. So our results showed that coconut oil increased HDL (‘good’) cholesterol more than olive oil and butter.

Because HDL helps remove LDL, the more good cholesterol you have compared to bad, the better for your health.

Table 2: Change in HDL (‘good’) cholesterol

Conclusions

In our study, coconut oil did not raise ‘bad’ cholesterol, despite being high in saturated fat. It also seemed to increase ‘good’ cholesterol.

These results were surprising and not in line with expectations about the effects of consuming saturated fat.

One explanation for the results is that coconut oil is rich in lauric acid, which may be processed in the body differently from other saturated fatty acids. Within the class of saturated fats, evidence suggests there are probably ‘good’ and ‘bad’ saturated fats. Identifying beneficial saturated fats is an important next step in understanding the health implications of consuming saturated fat in foods such as coconut oil.

Further studies are needed to find out the longer term effects of coconut oil, but our results suggest it is a comparatively healthy addition to the diet with respect to cholesterol.

This study has been accepted for publication in the medical journal BMJ Open and the full version will be available soon.