The big cholesterol-busting experiment

60% of people in the UK have high cholesterol, which can have serious health implications. Recent reports suggest that even slightly raised levels in our 30s and 40s could significantly raise our chance of developing heart disease. In the UK, around 8 million people are on statins, but the potential side-effects mean they aren’t suitable for everyone.

What is cholesterol?

Our bodies need cholesterol to function. For instance, it is used to make oestrogen, testosterone, vitamin D and other essential compounds. However, what do we mean by ‘good’ and ‘bad’ cholesterol? HDL stands for High Density Lipoprotein, and is often referred to as ‘good’ cholesterol. These gather cholesterol from our bloodstream and return it back to the liver for disposal. LDL, or Low Density Lipoprotein, is known as ‘bad’ cholesterol. These carry cholesterol from the liver around the body to the cells that need it. However, too much LDL in our blood means it can builds up in the walls of our coronary arteries, increasing the risk of coronary heart disease.

To tackle this cholesterol conundrum, Dr Scott Harding from Kings College London helped run a study to test three dietary changes. How easy is it to lower your cholesterol naturally? What foods should we aim to include in our diet, and which ones should we avoid?

The main experiment

In order to investigate the potential of individual dietary changes, 42 people were recruited with raised cholesterol levels. They were randomly allocated to one of three groups, and asked to make a single dietary change each. One group were asked to add in 75g of oats per day, another 65g of almonds, and the third group to cut down on cholesterol-rich foods. The focus of this last group was mainly replacing animal fats with vegetable based ones, which inevitably included saturated fats. This was measured over one month, while Michael Mosley undertook a longer diet which encompassed these changes with some additional measures.

Michael’s diet

Cholesterol is an issue that has long been close to Michael’s heart. Although he has taken statins to combat the issue, he was keen to see whether the same effects could be delivered by a natural means. To do so, he took on an a bigger diet challenge. While the main experiment demonstrated the strength of individual interventions; a combined approach offered the possibility of a more substantial impact.

Michael’s diet was based on a version of the Portfolio Diet. Dr David J. A. Jenkins developed this idea in 2002, incorporating four key cholesterol-busting dietary changes found individually to have lowered cholesterol. For eight weeks, Michael volunteered to try this approach. With a hectic travelling schedule, it tested how easy or difficult it would be to stick to in everyday life. As well as oats and almonds, the Portfolio Diet encompasses soy and plant sterols. Michael didn’t stick with all aspects of the diet, but each food had a different mechanism which said to lower LDL:

Oats

Oats contain sticky fibre called beta glucan which traps bile acids and prevents cholesterol being reabsorbed from the gut. Health claims have consistently been made for oats, and the positive effects they have on our blood lipids. Other foods high in sticky fibres include aubergine and okra.

Soy

Soy food and other bean proteins seem to inhibit cholesterol synthesis in the liver. Studies have shown that consuming 15-25g per day can lead to modest reductions in LDL.

Plant Sterols

Plant sterols block cholesterol by competing with it for absorption so cholesterol is lost from the body. It is very difficult to obtain the right amount from natural sources such as green leafy vegetables, nuts and seeds, but enriched margarines and yoghurts will easily give you the optimum amount recommended per day.

Almonds

In recent years, several studies have demonstrated that almonds can have a small effect, around 5%, on decreasing out cholesterol levels. They contain naturally occurring plant sterols, and are said to work by a combination of the other mechanisms of cholesterol lowering foods.

Michael’s results

Michael’s results were significant. After 4 weeks his total cholesterol went down by 25%, and LDL went down by 33%. At the same time his HDL did drop. However after another four weeks his total cholesterol went down by 30%, his LDL by 42%, and HDL went back up so his overall ratio went down over a unit altogether. This is undoubtedly on par with statins.

Modified Portfolio Diet: 2-3g phytosterols, 75g oats and 60g almonds per day.

Total cholesterol (mmol/L)

| Start | 4 weeks | 8 weeks |

|---|---|---|

| 8.0 | 6.0 (-25%) | 5.6 (-30%) |

LDL Cholesterol (mmol/L)

| Start | 4 weeks | 8 weeks |

|---|---|---|

| 5.5 | 3.7 (-33%) | 3.2 (-42%) |

HDL Cholesterol (mmol/L)

| Start | 4 weeks | 8 weeks |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | 1.6 (-25%) | 2.0 (-3%) |

TC:HDL Ratio (AU)

| Start | 4 weeks | 8 weeks |

|---|---|---|

| 3.9 | 3.9 (0%) | 2.8 (-28%) |

Group results

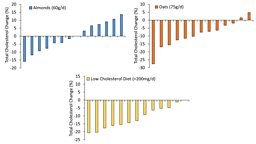

Looking at the mean results per group, oats showed good results on average across the group: a 9% and 10% reduction in LDL and total cholesterol respectively.

What we called the ‘low cholesterol’ diet also produced solid results, with an 11% reduction in total cholesterol, and an even greater reduction in LDL at 13%. The results of this diet are most likely the result of the volunteers’ reduction of animal fats. It’s very difficult to remove cholesterol from the diet without cutting back on animal fats, which have a higher amount of saturated fats. The volunteers were not told to reduce their fat intake, but Dr Scott Harding explained in reducing the animal fats, they likely also increased their polyunsaturated fats, and this probably caused the drops in their cholesterol levels.

The almonds appeared to show no overall effect on cholesterol levels, but the results for each individual volunteer in the study tells a different story. Half the group had their results raised by the diet, and half saw a drop – with one individual seeing a particularly significant drop of almost 20% in their total cholesterol.

Group results: percentage change in blood lipids by treatment

Almonds

| Risk marker | Change |

|---|---|

| Cholesterol | -0.3% |

| LDL | +1.6% |

| HDL | +0.3% |

| TC:HDL ratio | -0.8% |

Oats

| Risk marker | Change |

|---|---|

| Cholesterol | -8.7% |

| LDL | -10.2% |

| HDL | -5.7% |

| TC:HDL ratio | -3.6% |

Low cholesterol diet

| Risk marker | Oats |

|---|---|

| Cholesterol | -11.1% |

| LDL | -13.2% |

| HDL | -6.1% |

| TC:HDL radio | -4.5% |

Dr Scott Harding commented that:

‘There is enough data to support that it does work in general for the average person. But I think these data show that you really need to look at this with a health professional alongside, so you can make sure that this interventions working for you.

‘The concept of responders and non-responders is something that’s been appearing more predominantly in nutritional research in particular when you have people who respond very well and you have these people who respond either not at all or adversely and it’s an interesting angle to look at for research because this is really getting into personalising nutrition’.

If we take everyone into account, there were positive results right across the board, and some individuals had statin equivalent results, just by introducing one dietary change.

Overall, these results make clear that it is important to discover the right approach for you and monitor your own response alongside a GP or health professional.

Get your cholesterol levels measured first, try a single dietary change for 4 or more weeks, and then get them tested again afterwards. If one change works for you, then you could try adding a second and having them measured again – since the different foods work in different ways the results of combining more than one can give you an even bigger drop, as Michael discovered.

Useful links

-

![]()

Protocol for The Big Cholesterol Experiment

Did small dietary changes impact on blood cholesterol concentrations?