Have we made a schoolboy error?

When we think of World War One we picture weary soldiers ŌĆścoughing like hagsŌĆÖ cursing as they wade through ŌĆśthe sludgeŌĆÖ of the trenches.

We hear the ŌĆśgutteringŌĆÖ and ŌĆśgarglingŌĆÖ of a dying man and almost taste the ŌĆśgreen seaŌĆÖ of lethal mustard gas.

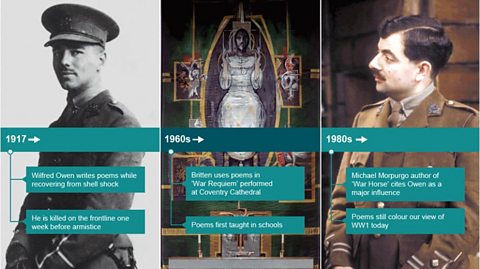

These vivid impressions sprang from the pen of Wilfred Owen, a junior officer in the trenches. He joined up as a patriotic idealist but became disillusioned as a result of first-hand experience of battle. It is easy to assume that the powerful words of this young man from Shropshire captured the true experience of the war. But is that assumption right? Or has our focus on poems like Owen's distorted our view of the war?

The poem we all remember

Owen is considered one of the greatest war poets, thanks in part to his moving poem Dulce et Decorum Est.

The poem describes a gas attack in the trenches and pulsates with a sense of horror and outrage. It has been taught in schools for 50 years.

Images courtesy of Topfoto, Getty Images, Mary Evans Picture Library and The Great War Archive, University of Oxford.

THE POEM WE ALL REMEMBER

Narrated by Ian McMillan

Dulce et Decorum Est, by Wilfred Owen

ŌĆ£Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! ŌĆō An ecstasy of fumbling,Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,And floundŌĆÖring like a man in fire or limeŌĆ”Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning,If in some smothering dreams you too could paceBehind the wagon that we flung him in,And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,His hanging face, like a devilŌĆÖs sick of sin.ŌĆØ

Those words graphically bring to life a terrifying gas attack on a British trench during the First World War.

TheyŌĆÖre from one of the most famous poems of the war, ŌĆ£Dulce et Decorum EstŌĆØ by Wilfred Owen.

After his terrible experience in the trenches he suffered from what they used to call ŌĆśshell-shock.ŌĆÖ And he wrote that in a psychiatric hospital in 1917. And itŌĆÖs brutal and bloody and graphic and it captures the feelings of men caught in the hell of war. Since I first read Dulce et Decorum Est at school, IŌĆÖve found OwenŌĆÖs work inspiring. Because he wears his heart on his sleeve and he spares us no detail. And he makes us confront warŌĆÖs darkest demons.

ŌĆ£If you could hear, at every jolt, the bloodCome gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cudOf vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, -My friend, you would not tell with such high zestTo children ardent for some desperate glory,The old Lie: Dulce et decorum estPro patria mori.ŌĆØ

The poem ends with OwenŌĆÖs sarcastic condemnation of jingoism: ŌĆ£Dulce et Decorum est pro patria mori,ŌĆØ which translates as ŌĆśIt is sweet and honourable to die for one's countryŌĆÖ.

Owen returned to the frontline in 1918, and just a week before the end of the war; whether he thought it was sweet and honourable or not, he died for his country.

At the time, he was just another soldier poet writing about the war. So why, after all these years, do we see Wilfred OwenŌĆÖs poetry as a defining image of World War One?

Wilfred Owen's rise to the top

A select group of well-educated soldier officers, including Wilfred Owen, came to view the war as one of pity and horror. This was a minority view but expressed through powerful and well-written poetry. In the 1960s a literary elite decided this was the most authentic view of the conflict because it chimed with their own anti-war feelings. This resulted in the publication of two key war poetry anthologies edited by Brian Gardner and Ian Parsons. These heavily featured Owen and other poets whose work seemed to suggest World War One had been futile.

One voice among thousands

While Owen wrote powerful poetry, he was just one of 2,225 men and women from Britain and Ireland who had poems published during World War One.

Owen wrote his anti-jingoistic poem as part of his therapy to overcome shellshock but his was just one, very personal, reaction to war. Other verses submitted to trench magazines reveal how soldiers also used humour and anti-German feeling to cope with the conflict. Much poetry written on the front line, such as by the poet Padre Woodbine Willie, was about everyday concerns like where the next rum ration was coming from.

Men in war larked about to ease the tension, like these two soldiers play-fighting in 1917. Images courtesy of Getty Images.

Women's experience of war

A quarter of poems published during World War One were by women compared to a fifth written by soldiers.

Their poetry reveals how women participated during the war - working and debating, suffering and sacrificing. As Evelyn Underhill wrote in her poem ŌĆśNon-combatantsŌĆÖ: ŌĆ£Never of us be said/We had no war to wage.ŌĆØ

Women on the homefront battled against the fear and terror they felt for the safety of their fathers, husbands and sons far away. ŌĆ£Theirs be the hard, but ours the lonely bed,ŌĆØ Evelyn Underhill wrote. Millions of women knew they could face a future without their loved ones.

Women were portrayed by some soldier-poets as innocent and idealistic ŌĆō but literature from the time suggests this was an unfair stereotype. The highly-regarded poet Charlotte Mew was all too aware of the shattering impact of war. In her poem 'June, 1915' she describes "a great broken world with eyes gone dim/ From too much looking on the face of grief, the face of dread.ŌĆØ

WomenŌĆÖs poetry and songs also reflected the new roles they took on during the war. By 1918 close to a million women worked in ammunition factories. The job was dangerous and working with TNT turned their skin yellow and caused their hair to fall out.

Despite this, female munition workers were proud to be ŌĆśdoing their bit.ŌĆÖ In the song We're The Girls From Arsenal they sang: ŌĆ£Some people style us ŌĆścanariesŌĆÖ/But weŌĆÖre working for the lads across the sea/ If it were not for the munition lassies/Where would the Empire be?ŌĆØ These lyrics show strong self-belief that they were making a difference - which indeed they were. They also reveal again the important connection felt between women at home and men on the front.

Hear the poem 'Non-combatants' by Evelyn Underhill, a munition workers' song and 'June, 1915' by Charlotte Mew. Images courtesy of Getty Images, Mary Evans Picture Library and Lebrecht photo library.

Should we change what we teach?

We've seen that relying on a small canon of poems gives us a very narrow view of both war poetry and the feelings and thoughts of people who lived through the conflict.

Historians have realised this and long since moved away from a 1960s mindset. However, many of us are still stuck with this skewed view of the war because we still learn about it through a handful of poets in English class. Is it time for this to change?

Secondary school English teacher, Sonya Gavaghan

I like teaching OwenŌĆÖs poems because the language and ideas are accessible to young people but students would benefit from tackling a wider selection of poetry. However we only have eight weeks in which to cover six poems as well as a Shakespeare play and so we must work toward exam essays. Teachers also tend to choose texts that are taught by other schools as it means there will already be a good variety of external resources available.

War poetry expert, Dr Santanu Das, King's College

I think we should definitely keep teaching Owen as he is a wonderful poet and is a vital part of the cultural memory of World War One. His poems are extraordinarily rich. However we should also widen the canvas and read alongside him war poems by other poets - male and female, combatant and civilian, and from beyond the UK and Europe ŌĆō who wrote powerfully about the conflict. War poetry is often read as history by proxy and this needs to change: we need to pay more attention to questions of poetic form.

Chair of examiners at OCR, Andrew Bradford

Our approach is always evolving and we do make changes to the literature we offer with each new syllabus. War poetry is nearly always included within the requirement for 'literary heritage' in English Language and English Literature. Our job is to offer interesting poems, which use vivid language and show how poetry works. ItŌĆÖs not the role of English to give a wider and balanced picture of the war, although OCR have set poems that offer different responses to the war.

Learn more about this topic:

WW1: Did the machine-gun save lives? document

Despite the thousands of deaths attributed to the use of the machine-gun in WW1, did its awesome threat actually save lives?

WW1: Does the peace that ended the war haunt us today? document

How has the modern world been shaped by decisions taken in the aftermath of WW1 - from conflict in the Middle East to the politics of the European Union?

WW1: Can the Treaty of Versailles help us tackle climate change? document

91╚╚▒¼ correspondent David Shukman asks whether the legacy of Versailles is still a useful approach to one of our most complex challenges: climate change.