From Gatling to game-changer

The machine-gun was a game-changing weapon of mass destruction. But did this awesome threat actually save lives?

When, in 1861, Dr Richard Gatling patented the Gatling gun – one of the first reliable hand-cranked machine-guns – his humanitarian vision was based on a desire to end wars. He believed that his invention would instantly convey to the military a reason not to go to war in the first place, or at least reduce the number of men who would be placed in harm’s way.

It's hard to fathom today that when war hit Europe in 1914 our military leaders were still unsure of the machine-gun's effectiveness and indeed its morality. They preferred to rely on tactics that were more accustomed to Napoleonic warfare. But it didn't take long for that notion to change, as the air of the Western Front became thick with an impenetrable swarm of lethal bullets, borne from Maxim's vision of the ultimate killing machine.

The Maxim revolution

Hiram Stevens Maxim described himself as a 'chronic inventor'.

He’d already invented everything from mousetraps to a steam-powered flying machine while in America, before turning his attention to weapons. In January 1884 he set about refining his machine-gun design in a basement flat in east London.

Man v Machine

One of Maxim's early prototypes could fire 666 rounds in a minute – around 11 bullets every second. In the battlefield conditions of WW1 this meant an average of 500 rounds a minute with a range of over 3,000 yards or 2,743m. Compare this to the best riflemen and their bolt action, single fire weapons, which at best could attain 15 rounds per minute with a range of just over 1,500 yards or 1,400m.

Paul Cornish from the Imperial War Museum explains how an American inventor based in London came to develop a deadly weapon which exploded onto the battlefields of WW1. (Clip from: The Machine Gun and Skye's Band of Brothers).

The Killing Zone

Germany's initial tactic of specialist machine-gunners and proliferation of Maxims gave them the upper hand in a defensive position.

Momentum shifted for British forces after the founding of the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) in late 1915.

Expertise in machine-gunnery was now in the hands of a specialist corps, which set about introducing new methods of fire. These methods required accurate maps, careful aiming of the guns (using clinometers to find the angle of sloping ground), range-finders and other equipment, not to mention a formidable amount of mathematical calculation.

'Enfilade' firing – where machine-guns are positioned on the flanks of the battlefield, crisscrossing the approaching enemy with sustained bursts of firepower – produced a 'killing zone' where trained gunners could inflict major losses.

Military historian Jack Sheldon explains how 'enfilade' firing was used during WW1. (Clip from: The Machine Gun and Skye's Band of Brothers).

Lethal firepower

Use the arrows to scrub through this slow-motion footage of a bullet fired into ballistic gel, which replicates the density of human flesh.

How did it feel under fire?

Military records and historical references show us that the real threat to soldiers in the trenches was the brutal artillery bombardments:

"Artillery was the killer; artillery was the terrifier; artillery followed the soldier to the rear; sought him out in his billet; found him on the march" (quote attributed to a French soldier on the western front). But despite this, it's the machine-gun which remains the weapon which pervades in the public mind as the relentless, dispassionate killer of men.

In this audio reconstruction of real-life accounts, we hear first-hand how it felt to come under fire as an allied machine-gunner relives the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Private Charlie 'Ginger' Byrne from the 2nd Battalion Hampshire Regiment was number three in a Vickers gun team which was attached to the 1st Battalion Newfoundland Regiment for the appalling, ill-fated attack at Beaumont Hamel on 1 July 1916. He was part of the second wave which advanced into a maelstrom of machine-gun fire.

Taken from diary extracts from 'I Survived, Didn't I?: The Great War Reminiscences of Private Ginger Byrne' (Pen and Sword Books Ltd) from his experiences of the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

The machine-gun: A life-saver in WW1?

Gatling v Maxim

So did Gatling's dream of saving men come to fruition on the western front or did Maxim's monster machine prove that increased firepower is the ultimate weapon of war?

Paul Cornish, Imperial War Museum

The machine-gun, like other weapons of war, was designed to take lives. Its users on both sides in the First World War did their best to maximise its ability to do so. Once expertise in machine gunnery was in the hands of a specialist corps, the results were formidable. Undoubtedly machine-guns could save lives among men to whom they were able to give such effective support. But overall this killing machine only increased the heavy battlefield casualties which characterised the First World War.

Jack Sheldon, German military historian

I am going to concentrate on German aspects of the story. I am leaving out consideration of the artillery, which was the biggest killer of all and am concentrating on automatic weapons. I have come to the conclusion that the machine gun did not save lives in the Great War – quite the reverse. The production and deployment of ever-increasing numbers of machine-guns was the main reason why the German army was able to continue the war into 1918. In other words, had it not been for a steadily increasing substitution of machinery for manpower, the war would have ended sooner.

Learn more about this topic:

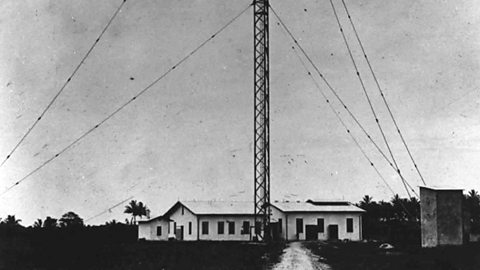

WW1: Why was the first German defeat in Africa? document

Togo in Africa saw the first battle between Allied and German forces in World War One. They fought for control of the Kamina wireless station.

WW1: What caused Verdun to be the longest battle of the war? document

Verdun was the longest battle of World War One, lasting a total of 300 days. Logistics, politics, pride and strategy all helped to prolong the conflict.

WW1: How did an artist help Britain fight the war at sea? document

Dr Sam Willis discovers how the British artist Norman Wilkinson developed dazzle camouflage to protect ships from German U-boats in WW1