How did an artist use Cubism to fight the war at sea?

How did an artist use Cubism to fight the war at sea?

Video transcript ÔÇô WilkinsonÔÇÖs dazzling idea

In 1917 Britain and her allies were losing hundreds of ships every month to German U-boats. These deadly submarines patrolled the waters of the United Kingdom watching for ships to destroy.

Their main targets were the merchant ships carrying the food and military supplies that sustained the allied war effort. It was vital to defend this cargo. Without it, BritainÔÇÖs war would be lost.

An English artist, named Norman Wilkinson, had a remarkable idea to protect these ships from the U-Boat threat.

During his wartime service in the Navy, Wilkinson realised it was impossible to conceal vessels effectively at sea. Most were painted a uniform shade of black or grey.

We commonly associate military camouflage with using neutral colours to blend in to the natural world.

The weather at sea, particularly around the British coasts, constantly changes. And so no single pattern of camouflage could hide these ships from a U-BoatÔÇÖs periscope.

WilkinsonÔÇÖs idea looked more like something from a cubist painting. Sweeping lines, large geometric shapes and violent contrasts of colour. It became known as dazzle camouflage. So how did Wilkinson use art to fight the war at sea?

Wilkinson's dazzling idea

In 1917, on a patrol ship in the dangerous waters around Britain, the artist and illustrator Norman Wilkinson had a brainwave.

As a Royal Navy volunteer in World War One, he had become all too aware of the threat from GermanyÔÇÖs U-boats.

Wilkinson decided he could use his artistic skills to protect Allied ships. He realised that it was impossible to paint a ship in camouflage that would hide it from the sights of a submarine commander. Instead, he proposed that the ÔÇťextreme oppositeÔÇŁ was the answer.

Rather than trying to make a ship vanish on the ocean waves, he developed a radical camouflage scheme that used bold shapes and violent contrasts of colour. His purpose was to confuse rather than conceal.

The art of confusion

Norman Wilkinson wrote to the Admiralty with his ideas for dazzle camouflage. Intrigued, they sent a ship to him at Devonport Naval Base. Wilkinson was ordered to oversee its painting to demonstrate how his plan would work.

Dr Sam Willis explains how dazzle camouflage was designed to help ships avoid enemy torpedoes. (With images from the Norman Wilkinson Estate, Imperial War Museum, Getty, Topfoto)

The art of confusion

Norman WilkinsonÔÇÖs dazzle camouflage was certainly eye-catching. So how could it possibly help a ship avoid being torpedoed?

Wilkinson never expected for his camouflage to hide a ship, but to confuse a U-boat commander before heÔÇÖd even fired his torpedoes. When the periscope broke through the surface of the water, he would have only seconds to locate his target and fire.

He had to be quick to avoid being spotted. U-boats were very vulnerable, and merchant ships were often armed to protect themselves. A ship was a moving target. To score a hit, he had to fire the torpedo ahead of the vessel.

Wilkinson wanted dazzle camouflage to make this more difficult. Its contrasting colours and shapes broke up a ship's form. This would make it more difficult for a Uboat to work out a shipÔÇÖs speed and direction.

The Admiralty made Wilkinson the head of a new dazzle camouflage section. He assembled a team of artists and model-makers at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. They created hundreds of unique camouflage patterns.

One of the camouflaged vessels was the small warship HMS M33, here at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. She has been restored to her dazzle scheme. Built in 1915, she served during the Gallipoli Campaign, and is one of three surviving British warships from World War One.

WilkinsonÔÇÖs camouflage was also rolled out across BritainÔÇÖs merchant fleet. It also impressed the American Navy, who applied it to their own ships. One US newspaper described their fleet as a "flock of sea-going Easter eggs".

Painting the fleet

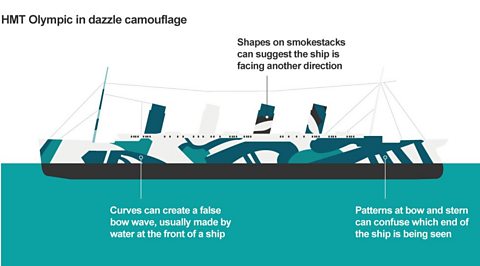

WilkinsonÔÇÖs Dazzle Section developed hundreds of camouflage schemes, for large ships and small. Each side of a ship had a different pattern. One vessel was the enormous Olympic ÔÇô sister ship of the Titanic. Olympic became a troop ship during WW1 and was repainted in dazzle. She shows some of the techniques used by dazzle designers. Bold shapes at the bow and stern break up the form of the vessel. Angled lines suggest the distinctive smokestacks could be leaning in another direction. And curves on the hull could be mistaken for the shape of the ÔÇśbow waveÔÇÖ ÔÇô created by water at the front of a fast-moving ship.

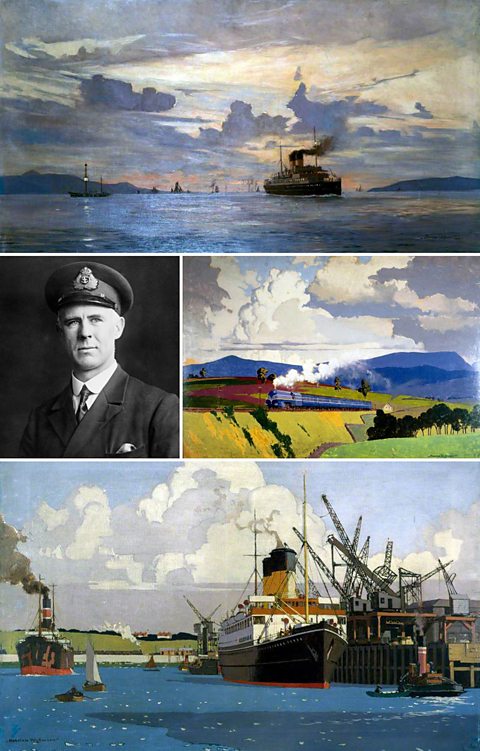

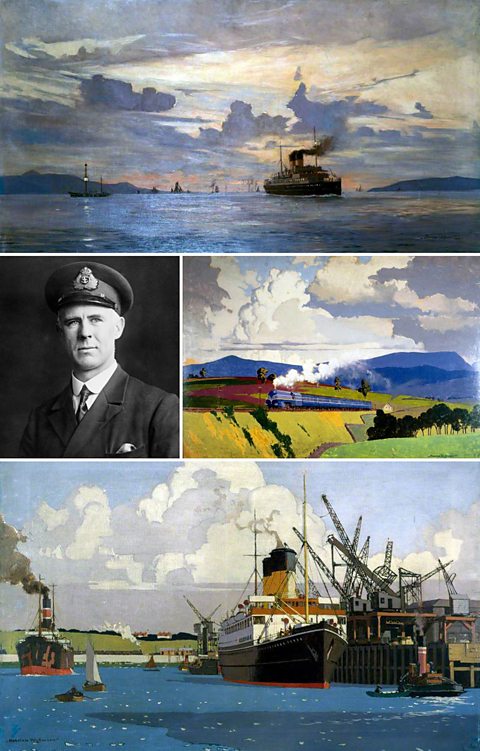

The man behind the brush

WilkinsonÔÇÖs dazzle designs have been compared to what in 1917 was considered a revolutionary movement in modern art, called cubism. It was made famous by artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

While there is an overlap in appearance between dazzle and cubist art, Wilkinson himself was anything but a modernist. He was a celebrated marine painter and talented poster artist.

He was commissioned to create paintings for the elegant smoking rooms on board the Titanic and the Olympic. Wilkinson was passionate about ships and the sea. It inspired him to travel from Europe, to the US, Bahamas and Brazil.

He also produced beautiful landscape art. His work was used by The London & North Western Railway and London Midland & Scottish Railway to advertise their routes.

WilkinsonÔÇÖs art now takes pride of place in collections including the National Maritime Museum, Royal Academy of Arts and the Royal Society of British Artists.

Born in 1878, he studied at Portsmouth and Southsea School of Art, and found early work selling his drawings to newspapers. He built a career at the Illustrated London News before signing-up for the Navy after the outbreak of war in 1915.

On submarine patrol he faced the dangers of the Gallipoli campaign, then returned to Britain in 1917 to serve on a minesweeping ship. It was here that his idea for dazzle was born.

A colourful impact

In 1917 people were astounded by harbours full of colourful ships.

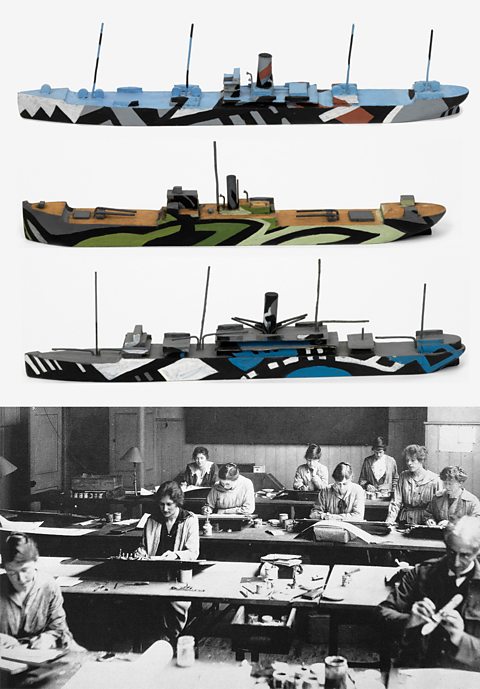

But some of the visual impact of WilkinsonÔÇÖs camouflage is lost today in the black and white images we have of World War One. The striking colours can still be seen on hundreds of model ships in the collection of the Imperial War Museum.

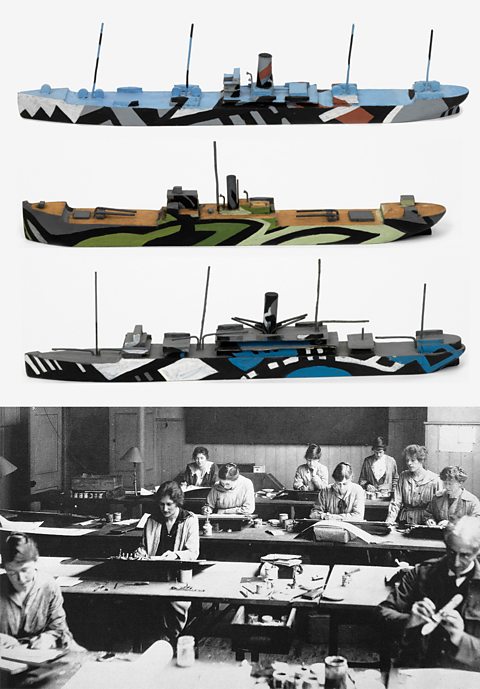

These were made by the Dazzle Section at the Royal Academy of Arts, at Burlington House in London. Scale models were painted and used to test dazzle designs. They were placed on a rotating turntable and viewed through a periscope.

This allowed WilkinsonÔÇÖs team to see how dazzle distorted a shipÔÇÖs form as if it were travelling in different directions. Wilkinson believed that using strong contrasts, with light and dark greys, blues and greens, was most effective.

Wilkinson appointed dock officers at ports around Britain. They supervised the painting of ships from the finished designs. One dock officer was the artist Edward Wadsworth. He was a founder of Vorticism - a British art movement that grew out of Cubism.

The Admiralty experimented with various camouflage ideas during WW1. They had considered similar proposals by US artist Abbot H Thayer and the Scottish zoologist John Graham Kerr.

However, it was WilkinsonÔÇÖs scheme that won them over. After the war the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors awarded him ┬ú2000 and recognised him as the creator of dazzle.

The legacy of dazzle

The effectiveness of dazzle camouflage was never scientifically proven in World War One. However, recent research from the University of Bristol that suggests it could still have a role on modern battlefields.

A study by the School of Experimental Psychology found dazzle can alter the perception of speed, as long as the target is moving fast enough. Participants saw two moving patterns on a computer screen, one plain and one dazzle. They were asked to estimate which was travelling faster. There was a reduction of around seven per cent in the perceived speed of some high contrast dazzle patterns.

This would not have made a difference to a WW1 U-boat commander hunting slow merchant ships. But it could make a difference today where handheld rocket propelled grenades are fired at short range against moving vehicles.

Dr Nick Scott-Samuel, who led the study, says: ÔÇťIn a typical situation involving an attack on a Land Rover, the reduction in perceived speed would be sufficient to make the grenade miss by about a metre. This could be the difference between survival or otherwise.ÔÇŁ

Sam Willis examines the influence of dazzle beyond WW1. (Images from Getty, National Gallery of Canada)

The legacy of dazzle

By the end of the First World War, dazzle camouflage had been applied to more than 2000 ships. And the number of vessels sunk by U-boats had begun to fall. However, there is no definitive proof that this was all thanks to Wilkinson's scheme.

Dazzle camouflage was used alongside other U-Boat countermeasures and merchant ships sailed in convoys protected by naval escorts.

The Admiralty had clearly been impressed by Norman Wilkinson's plan, and had rolled it out as quickly as possible. But they did not have conclusive evidence of effective it was.

What they did agree upon, however, was the value of the scheme as a moralebooster. It made the crew on these spectacular ships feel safer from attack.

The US Navy continued to use dazzle into World War Two, until development of radar technology made it redundant. Wilkinson also went back to work in World War Two. He helped to disguise Britain's airfields - this time using more traditional colours.

The military value of dazzle remains unclear, but it certainly had an impact in the art world. The artist Edward Wadsworth worked for Wilkinson supervising the painting of dazzle ships. He was one of the founders of the Vorticist art movement. The dazzle elements in his work are clear to see.

The most famous cubist artist of them all, Picasso, is said to have ÔÇťstopped spellboundÔÇŁ on the streets of Paris when he saw a tank painted in a dazzle pattern. Picasso proclaimed: "C'est nous qui avons fait ca". It is us who created that.

Learn more about this topic:

WW1: Did the machine-gun save lives? document

Despite the thousands of deaths attributed to the use of the machine-gun in WW1, did its awesome threat actually save lives?

WW1: Why was the first German defeat in Africa? document

Togo in Africa saw the first battle between Allied and German forces in World War One. They fought for control of the Kamina wireless station.

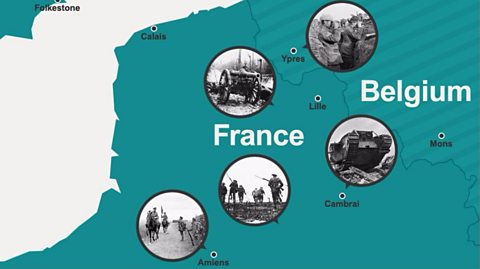

WW1: What can today's soldiers learn? document

Over 100 years on from the start of WW1, the British Army is learning about the conflict that shaped so much of our world today.