Shaping the modern world

From conflict in the Middle East to the politics of the European Union, there are many aspects of the modern world that can be traced back to decisions and actions taken in the aftermath of World War One.

As victors, Britain, France and the United States faced an enormous challenge: how to agree the peace terms for a war that had led to the deaths of over 16 million soldiers and civilians, and caused the collapse of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires. These peace terms were to shape the balance of power in the world for decades to come; in some parts of the world, only now is that balance being redefined.

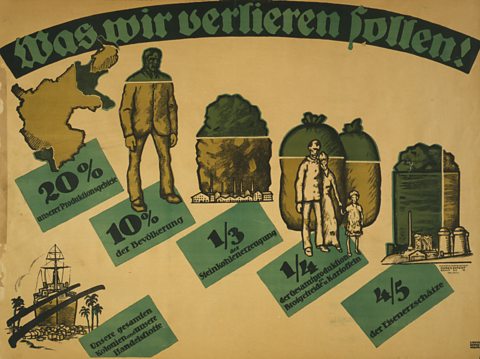

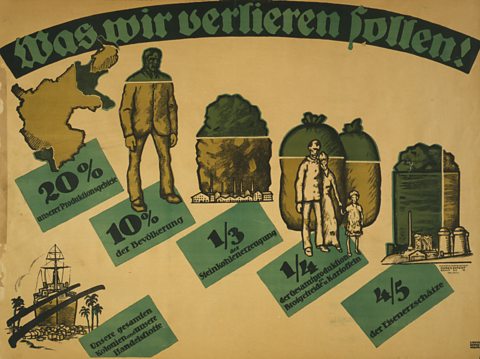

In Europe, Germany was made to shoulder the blame for the bloodshed of the previous four years, and lost territory to its neighbours as the map of the continent was radically redrawn. The humiliation felt by many Germans would have devastating repercussions. And in the Middle East, Britain was faced with the consequences of making seemingly contradictory promises to potential allies during the war, the impact of which is still being felt in the region today.

How WW1 changed the map of Europe

The Treaty of Versailles and its sister treaties, the Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye and the Treaty of Trianon, dismembered the old Austro-Hungarian and German Empires. Four new countries appeared on the map, and others such as Romania saw their borders radically redrawn. Germany lost land - mostly to Poland - and there were now German speaking enclaves in every country around the German border.

The Treaty of Versailles

The most controversial part of the Treaty of Versailles was the so-called war guilt clause. It has often been blamed for causing World War Two, by creating the resentment and anger among the German people that Adolf Hitler exploited to win popular support.

In 1923, Hitler declared that the Treaty 'was made in order to bring 20 million Germans to their deaths and to ruin the German nation.' He set out three demands: 'setting aside of the Peace Treaty; unification of all Germans; land and soil to feed our nation.'

Reparations

Germany was asked to pay 132 billion gold marks (about £6.6 billion - around £280 billion in today's money) to the Allies. British economist John Maynard Keynes condemned the settlement, predicting it would lead to the economic collapse of Germany and 'Revolution, before which the horrors of the later German war will fade into nothing'.

Germany's economy did spiral into chaos in the mid-1920s, and although it recovered, the stock market crash of 1929 led to economic meltdown. Most historians today do not think that the reparations were to blame for Germany's economic problems. But they were an easy target for extremists like Hitler, who exploited them to attack and undermine German democracy.

Demilitarisation

Germany had to reduce its army to 100,000 men, and destroy or hand over its tanks, air force and U-boat fleet. It was also forced to keep all military forces out of a 30-mile stretch of the Rhineland, which bordered Belgium and France.

In 1936, Hitler ordered German troops to march back into the Rhineland. It was the first of many acts that would breach the Treaty. This defiance rekindled a sense of national pride among many Germans. In their eyes, Germany was once again a strong power.

Land and people

Germany lost all its overseas colonies in Africa and Asia, and over a tenth of its land in Europe, including some of its most productive industrial areas. Many of the countries created around Germany, such as Czechoslovakia and Poland, now controlled territory with large ethnic German populations.

Hitler spoke about 'the fate of the Germans living beyond the frontiers of Germany who are allied with us in speech, culture, and customs'. In 1938, he annexed Austria and part of Czechoslovakia, in the name of uniting ethnic Germans. The following year, acting on his promise over 16 years earlier to provide land and soil to feed the German people, he invaded Poland. World War Two had begun.

The effect on one town in Poland

The story of the Polish town of Katowice is a microcosm of the story of 20th century Europe: nationalist fervour after Versailles, the rise of the Nazis, World War Two, the division of Europe during the Cold War, and the growth of the European Union.

Diplomatic games in the Middle East

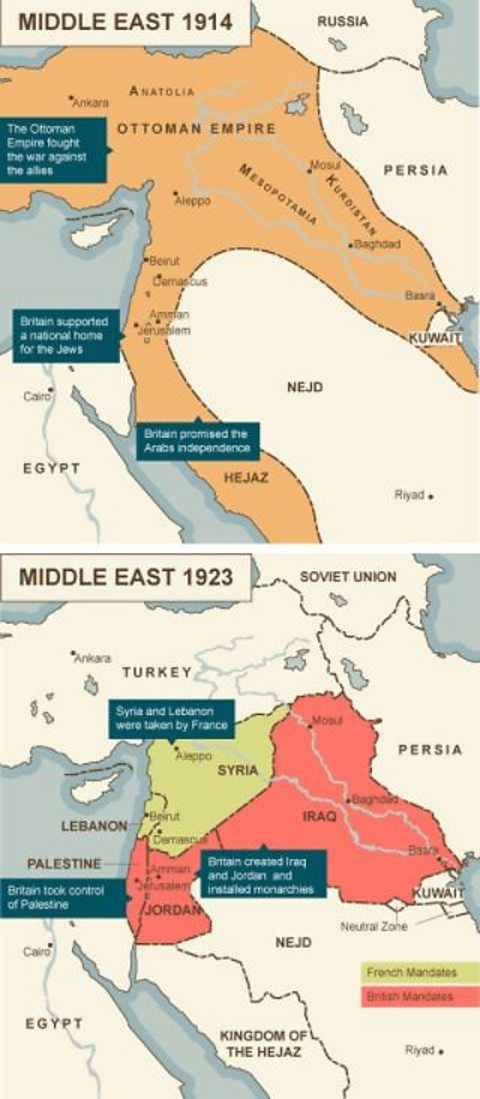

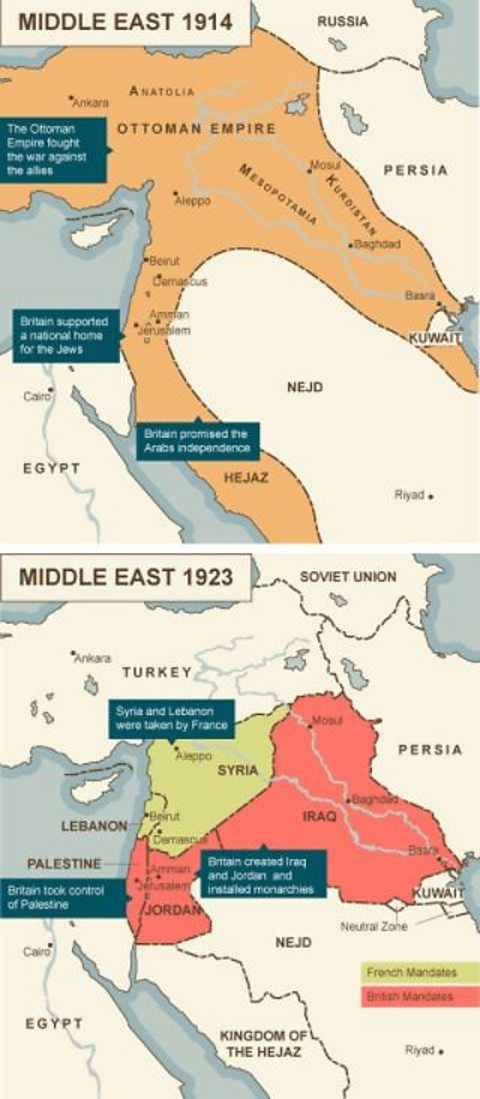

Just as in Europe, the Middle East was divided by a series of treaties agreed at peace conferences. Unlike in Europe, these divisions were largely the result of agreements already made during the war.

Before 1914, the Middle East was dominated by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans joined Germany and Austria-Hungary in their fight against the Allies, and suffered defeat alongside them. This led to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, marking a turning point in relations between the Arab World and the West.

During the war, Britain had fought the Ottomans in Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq). As it did so, British diplomats made a series of seemingly contradictory promises to potential allies.

Husayn-McMahon Correspondence, 1915-1916

This series of letters between the Sharif of Mecca, Husayn Bin Ali and the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, declared the Arabs' intention to revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Britain would support this revolt in return for recognition of Arab independence - although the exact territory that would become independent was not made clear.

Sykes-Picot Agreement, 1916

This secret agreement, made less than two years after the start of the war, was negotiated by British and French diplomats Sir Mark Sykes and Fran├žois Georges-Picot. The two countries decided to divide the Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire between them. France would take what is now Syria and Lebanon, and Britain would take what is now Iraq and Jordan, along with the Gulf States, which it already controlled. Palestine was to be under international control.

Balfour Declaration, 1917

In 1917, Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote a letter to the Jewish Zionist Lord Rothschild in which he declared the British GovernmentÔÇÖs support for an 'establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish peopleÔÇŽ it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine'.

The precise motivation for Balfour's letter is unclear, but the British may have hoped to influence Jewish communities in Russia and the United States to support the Allied war effort. They may also have wanted to reward leading Zionist Chaim Weizmann, a Jewish chemist (later the first President of Israel) who had helped Britain develop a large scale manufacturing process for shells.

The Middle East: What happened next?

The borders drawn by Britain and France were in some places largely arbitrary. They divided people of the same ethnicity, disrupting a pattern of life which had developed over hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

In Iraq and Jordan

In Iraq, the British installed Faisal, son of the Sharif of Mecca, as King. His inauguration was a bizarre affair. Unsure what music was appropriate, the British band played 'God save the King'. Resentment against the British led to the growth of Arab nationalism, and the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown in a bloody coup in 1958. This was the first in a series of coups which installed nationalist military dictatorships, culminating in the regime of Saddam Hussein.

In Jordan, Faisal's brother Abdullah declared himself Emir. The British acquiesced, keen to have a friendly regime that would not threaten oil pipelines coming from Iraq. Jordan became independent in 1946, and Abdullah's descendants still rule over the country today.

In Syria and Lebanon

France divided its Mandate into two republics.

Lebanon was predominantly Christian, with Muslim, Druze and Alawite minorities, although Christians later became a minority. The French introduced a complex system of ethnic quotas for all jobs in government, a version of which is still in place today. This makes Lebanese politics highly sectarian and often unstable.

In Syria, as in Iraq, a rise in Arab nationalism led to a series of military coups in the 1960s. In 1970 Hafez al-Assad seized power, and ruled until his death in 2000, when he was succeeded by his son Bashar.

In Palestine

The numbers of Jews emigrating to Palestine increased under British supervision, especially after Hitler came to power in 1933. Arab resentment also increased.

After the Holocaust, in which over 6 million Jews were killed, there was a surge of Jewish immigration to Palestine. Britain struggled to contain the crisis, and handed the task of deciding the future of Palestine to the United Nations.

The UN voted to divide Palestine into two states: one Arab, one Jewish. In 1948, Israel declared its independence; the first Arab-Israeli war began the moment the British left.

In the Arabian Peninsula

One of the many tribes in the Arabian peninsula, the Saudis, succeeded in conquering a large part of the region - including the valuable kingdom of the Hejaz, which contained the holy sites of Mecca and Medina. In 1932, the modern state of Saudi Arabia was declared, covering most of the peninsula. At first, Saudi Arabia was one of the poorest countries in the Middle East - until the discovery of huge reserves of oil in 1938.

Does the peace still haunt us today?

Now that we have the benefit of over 100 years of hindsight, what conclusions can we come to about the decisions made in the months and years that followed the end of World War One?

Political historian, Dr George Kyris

World War One doesn't haunt Europe today - instead the legacy has been a positive one in the long run. Today the European states are closer than ever before and this is because we have learnt from the mistakes made in the peace treaties of World War One.

Amongst other things, they failed to provide long-term stability because they were focused on punishment. Therefore after World War Two the focus was on inclusion and cooperation on all sides. So now we have security on the continent and economic and political cooperation.

Writer and historian, Timothy Garton Ash

If you talk to people in Hungary, it will not be many days before you hear mention of the word Trianon. They are not talking about a holiday on the outskirts of Paris. They are talking about the treaty that truncated the territory of what was then Hungary. Over 100 years later, it is still present in the Hungarian national memory ÔÇô and still shaping Hungarian politics. The peace treaties at the end of WWI have a long afterlife, and nowhere is this more visible than in Central and Eastern Europe.

Middle East expert, Prof. Beverley Milton-Edwards

In many respects the region [the Middle East] has still to recover from the creation of false borders, false flags and false states after World War One ÔÇô states like Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, which are crippled with war and conflict.

The ideologies of nationalism and radical Islamism were brought forth at this time as a reaction to foreign intervention and control, and powerfully resonate in the region today. When the Allies invaded Iraq in 2003, many in the region, including Islamist radicals and nationalists, could draw on a century of bitterness against ÔÇśforeign imperialists'.

There are many political movements in the Middle East today, which are based on the idea that they were cheated of their chance to have their own national independence after World War One.

Learn more about this topic:

WW1: Can the Treaty of Versailles help us tackle climate change? document

91╚╚▒Č correspondent David Shukman asks whether the legacy of Versailles is still a useful approach to one of our most complex challenges: climate change.

WW1: How did an artist help Britain fight the war at sea? document

Dr Sam Willis discovers how the British artist Norman Wilkinson developed dazzle camouflage to protect ships from German U-boats in WW1

WW1: What caused Verdun to be the longest battle of the war? document

Verdun was the longest battle of World War One, lasting a total of 300 days. Logistics, politics, pride and strategy all helped to prolong the conflict.