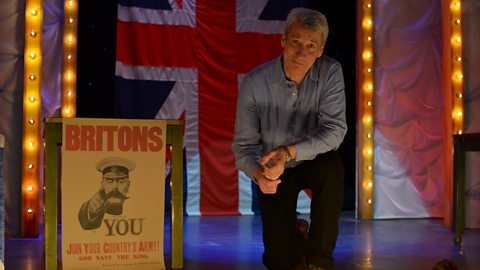

CAN THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES HELP US TACKLE CLIMATE CHANGE?

Presenter â David Shukman, Science Editor, 91ČČąŽ News

Introduction

Climate change is described by governments the world over as one of the most pressing threats of our time.

So for decades, leaders have come together for huge global conferences to try to find solutions.

Weâve become used to massive gatherings of this kind but rewind a hundred years they were a pretty new idea.

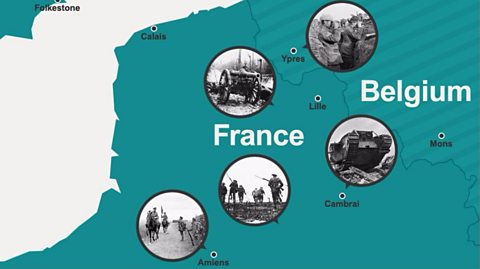

Four bitter years of World War One left millions dead and empires ruined.

This huge challenge needed a response on a scale that had never been seen before.

In 1919, leaders from the four corners of the world gathered in Paris to discuss and negotiate a peace deal together.

The Treaty of Versailles that they eventually signed is often criticised â usually for the perception that it led to the Second World War. Well, Versailles had another legacy as well as a model for international cooperation based for the first time on a permanent body âThe League of Nations. And this in turn gave way to a body that weâre familiar with today â the United Nations.

This is Central Hall in Westminster and this was the venue back in 1946 for the first ever meeting of the United Nations General Assembly.

Just as in Paris almost 30 years earlier, delegates had high hopes as they gathered from around the world.

So I want to explore how useful the blueprint launched at Versailles has been for something as complicated as climate change.

The whole world around a table

Almost 100 years ago, in 1919, the world's leaders faced the grave challenge of rebuilding following the chaos and destruction of World War One. What they did set the blueprint for how international diplomacy has been organised ever since.

The Treaty of Versailles, and the Paris peace conference that led to it, established a new world order; one in which world affairs would be discussed and settled in big, open, international conferences.

As a 91ČČąŽ correspondent I've been to my fair share of these conferences over the years, and I've seen the slow progress made at them when politicians try to tackle the major global issues of our times. I'm interested in what we can learn from the successes and failures of this model, and whether the legacy of Versailles is still a useful approach to one of our most complex challenges: climate change.

The world in one city

When world leaders gathered in Paris in 1919, the mood was one of ambition, excitement and idealism. But what would they achieve?

CAN THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES HELP US TACKLE CLIMATE CHANGE?

Presenter â David Shukman, Science Editor, 91ČČąŽ News

Step 2: Audio slideshow: The World in One City

Armistice Day â the 11th of November 1918 â was greeted with euphoric celebrations across Europe and beyond. Four long years of World War One had finally come to an end.

To negotiate a lasting peace deal, world leaders gathered in Paris led by the so-called âBig Threeâ â the prime ministers of Britain and France and the President of the United States.

But away from the cheering crowds, they had a serious crisis on their hands.

Empires had collapsed. There were refugees, food shortages and mounting social unrest. The leaders were well aware of the threat of revolution spreading from Russia. They needed urgent, decisive action.

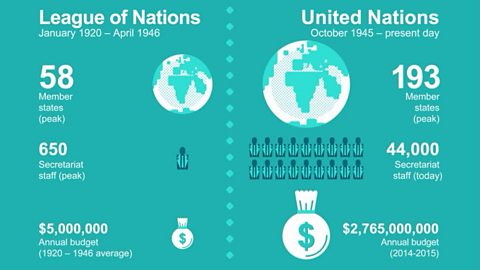

So delegates from around the world poured into Paris over the months of 1919.

This was an international conference on an unprecedented scale.

Not only were there diplomats, campaigners like suffragettes arrived in Paris to petition for their cause too.

And, of course, hundreds of journalists were eagerly waiting to wire every development to the rest of the world.

The leaders made bold decisions â reshaping nations and creating new ones. Poland became an independent state.

There was also severe punishment for Germany â stripped of land and military might. Despite some opposition, the key powers pushed through their decisions.

News of the signing reached the streets of Paris and parties erupted across Britain.

The Treaty of Versailles ushered in a new world order.

The League of Nations

The establishment of the League of Nations was one of the key outcomes of the Treaty of Versailles. It would be an international organisation which could unite nations in an attempt to make sure the carnage of the previous four years didnât happen again.

Early success

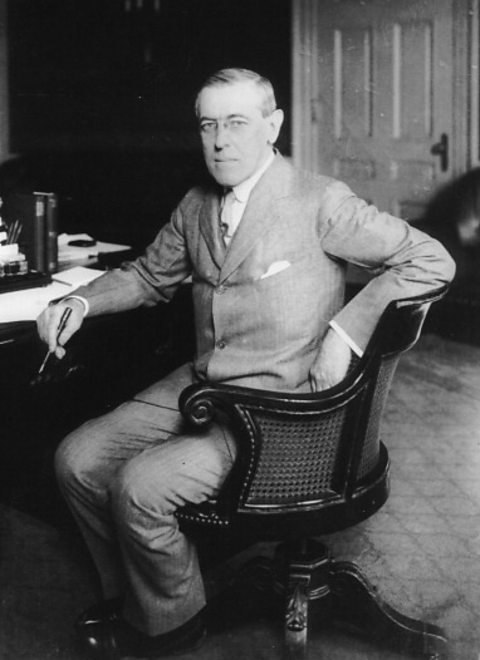

The League enjoyed a number of notable successes. It solved border disputes between a number of European states that might once have led to wider regional conflicts. In the field of health it standardised vaccination against diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus and tuberculosis. It also provided aid and support for 1.5 million refugees in post-war Turkey. By 1935, 58 countries were members.

A major setback

The League had no formal power, other than that of its member states, that could carry weight on the global stage. It suffered a major setback when Woodrow Wilson was unable to convince the US Senate that America should join. Without the involvement of a key power, there was a limit to what it could achieve.

Powerless to prevent a new world war

The organisation suffered more setbacks during the 1930s when the losing powers of the First World War sought to discredit it. When Adolf Hitler broke the terms of the Versailles Treaty by building up the German military, the League was powerless to act. Unchecked by the international community, the outcome of Hitlerâs actions was the Second World War, which broke out in 1939, just 20 years after the establishment of the League.

Ultimately the League had failed in its primary purpose: preventing another world war. It was disbanded in 1946. Yet many of its founding principles were inherited by the United Nations, which was established after World War Two, and still shapes much of international politics today.

From the League to the UN

The United Nations continues many of the aims and methods of the League of Nations. But it does so on a far larger scale.

The UN's big successes

The United Nations often makes the headlines when countries are struggling to reach agreement. We tend to talk less about its successes. But there have been significant moments when it has brought nations together to make the world a safer place.

Protecting the ozone layer

Pollutants released into the environment by individual countries can have effects around the world. In the 1970s and 80s, scientists realised that chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases from fridges and aerosol cans were reacting with the layer of ozone gas, which screens out harmful ultra-violet rays from the Sun, high in the earth's atmosphere. Satellite images revealed a hole growing over the continent of Antarctica.

In 1987, 46 countries adopted the Montreal Protocol by committing themselves to halving their CFC emissions in just over a decade. Since then, a series of amendments has strengthened control on CFC gasses. Now over 200 countries have signed up. Damage to the ozone layer is expected to be reversed by the middle of the century.

Eradicating smallpox

Viruses are no respecters of international borders. Smallpox was one of history's most feared plagues, killing and maiming victims on six continents. A vaccine was discovered in 1796, and several countries declared themselves free of the disease by the middle of the twentieth century. However, the growth in international travel meant that no-one could be safe without a worldwide effort.

In 1967, the United Nations' World Health Organisation began a global vaccination programme. The disease was officially declared eradicated just 13 years later. Smallpox is just one of a number of infectious diseases, which have been brought under control through international co-operation.

Regulating air travel

Flying is inherently risky, and international travel requires co-operation between many different teams of people in different countries. They operate in different time zones, often speak different languages, and may even use different systems for measuring distance and height.

Yet air travel has remained one of the safest forms of transport. The Convention on International Civil Aviation in 1944 set the blueprint for co-operation on international flight and it remains governed by stringent protocols. This agreement now ensures the safety of over 10,000 international flights a day.

Tackling emissions

The Kyoto Protocol was the worldâs first attempt to limit emissions of greenhouse gases. It came into force in 2005 after it was ratified by 55 countries. But it fell far short of its aims.

The worldâs two leading emitters were not included. China, as a developing nation, was exempt. The United States never ratified the treaty. And, for the countries taking part, the targets for cuts in emissions were widely criticised for being too modest.

CAN THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES HELP US TACKLE CLIMATE CHANGE?

Presenter â David Shukman, Science Editor, 91ČČąŽ News

A new conference for today

DAVID SHUKMAN

Big United Nations conferences have produced many successes. But when it comes to climate change theyâve only really yielded one modest achievement â the Kyoto Protocol â and not much else.

I know, because Iâve been to many of these events myself.

ARCHIVE REPORT

For five precious hours there was frantic shuttling âĶ on this day of high stakes and difficult progress the huge crowds strain âĶ behind the scenes there is a constant shuttle âĶ rumours spread âĶ Barak Obama is about to give a news conference.

DAVID SHUKMAN

The richest countries worry that their economies may suffer if their targets for cutting carbon emissions are too tough.

The poorest countries fear that theyâll suffer from the worst impacts of climate change and that they wonât get enough financial help.

And the big oil producers like Saudi Arabia argue that theyâll be hit by any move away from fossil fuels.

At recent conferences, two key players have emerged â China and America. China is the worldâs biggest polluter so America says it must cut its emissions; but China says itâs still developing and America must do more because itâs polluted so much already.

So unlike in Versailles in 1919 when the big powers wanted a deal, this time theyâre in deadlock.

And to make things even harder when the doors to a conference are open to all countless voices need to be heard.

Delegates from nearly 200 countries arrive each with their own agenda.

The atmosphere can be quite chaotic â people donât often know what on earth is going on.

Scientists say that action on all of this is urgently needed and world leaders are gathering in Paris in 2015 to talk about climate - just as their predecessors gathered there nearly a century ago to talk peace. But it doesnât look as if the Versailles model on its own willprovide the answer.

Learn more about this topic:

WW1: What can today's soldiers learn? document

Over 100 years on from the start of WW1, the British Army is learning about the conflict that shaped so much of our world today.

Jeremy Paxman: The Great War. collection

In this series of short films, Jeremy Paxman looks at how World War One transformed the lives of the British people.

World War One with Dan Snow. collection

Historian Dan Snow introduces some of his favourite history clips from the 91ČČąŽ archive, perfect for studying World War One with your class.