8 brilliant definitions of beauty, from Aristotle to Aguilera

What is beauty? It’s one of the oldest questions in Western philosophy. Once, great thinkers considered it to be a value as solid and unchanging as a hunk of marble, prized alongside goodness, justice and truth. Today the concept of beauty is much more contentious, presumed to exist largely in the eye of the beholder. Is beauty only skin-deep or is it something more profound?

To coincide with 91热爆 Radio 2’s special focus on beauty for , Skye Sherwin looks at the changing face of beauty as imagined by a few of history’s great aesthetes.

1. Aristotle: beauty is symmetry

The Golden Ratio: Possibly the best rectangle in the world

Find out more about the Golden Ratio.

For the Ancient Greeks, beauty was no woolly matter of personal taste. According to Aristotle, beauty could be measured. Literally. “The chief forms of beauty are order and symmetry and definiteness, which the mathematical sciences demonstrate in a special degree,” he says in Metaphysics. There’s even a beauty formula - the Golden ratio, a set of proportions found in nature and applied by man to all manner of visual culture.

Aristotle’s values are written into the way the Greeks built the world: from the mathematical proportion of their architecture to the way they composed the twisting bodies of discus throwers in sculpture. This kind of objective beauty, conjured with rulers and set squares, would continue to obsess the artists of the renaissance hundreds of years later; their buildings and paintings, including Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, were often structured around mathematical formulas.

2. Keats: beauty is truth

Bright Star

The trailer for Jane Campion's film about John Keats, a 91热爆 Films production.

The romantic poet John Keats was one of literature’s great beauty obsessives. He coined some of the best-known quotes on beauty: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all,” he concludes in his 1819 work Ode on a Grecian Urn. There’s also the opening line of his earlier poem Endymion: “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.”

Around the time Keats wrote his ode, his circle were cooing over the idealised beauty of the figures in the Elgin marbles and other classical artefacts that had recently gone on show in the British museum. For Keats, beauty is not the plaything of the cultural or historical moment, dependent, as the proverb says, on the eye of the beholder. Beauty survives. And in this ode, beauty means art. It’s basically the same thing as immortality. While man will perish and his cares fade and be forgotten, art will have the upper hand over nature.

3. Wilde: beauty is genius

“Beauty is a form of genius - is indeed higher than genius as it needs no explanation.” So lectures the corrupt Lord Henry in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Wilde was setting up his characters for a fall. Dorian Gray is magically gifted an eternal beauty that conceals and enables wicked debauchery.

What Lord Henry says is typical of your dandy decadent at the end of the 19th century. This fashionable peacock making witty quips as he sips champagne in London’s clubs has seen it all, has no need for morality and pursues beauty and pleasure at the expense of everything and everyone, because nothing else really matters. It’s a grotesque version of aestheticism, the Victorian beauty cult that rejected the era’s moralising in favour of ‘art for art’s sake’. “[Beauty] cannot be questioned,” Lord Henry continues, an idea that Wilde dismantles to thrilling, tragic effect.

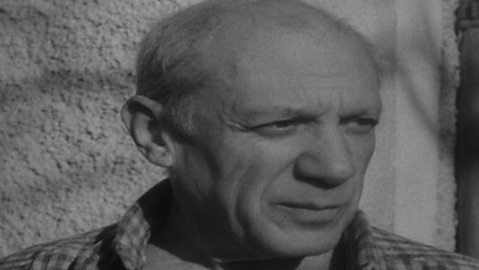

Picasso: beauty is dangerous

Modern Masters: Pablo Picasso - 91热爆 Archive

91热爆 archive of Pablo Picasso at his home in Vallauris, France.

“Beauty? To me it is a word without sense because I do not know where its meaning comes from nor where it leads to.” By the time Pablo Picasso said this, modernist artists of the early 20th century had thoroughly exploded beauty as a value. Beauty, they felt, was all about tradition and hand-me-down notions of what’s attractive. The modernists wanted to reimagine reality for the brand new machine age - which in Picasso’s case meant mixing up art hierarchies, taking inspiration from so-called primitive art or cutting up the world into Cubist planes.

Also, as Picasso implies, beauty is a hazy idea that can take you into dangerous territory. The Nazis had an ideal notion of singular beauty that they used to justify their persecution of anyone who didn’t fit. Hitler’s favourite director Leni Riefenstahl, who created what were intended as world-conquering gorgeous images of athletes at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, stated she was “fascinated by beauty”. In short, beauty had never looked so bad.

5. Chanel: beauty is self-expression

Silk, sass and shimmer: William Banks-Blaney on Coco Chanel

The vintage couture expert explains why 1924 Ribbon Dress still holds sway on catwalks.

Few were better qualified to comment on how beauty operates at ground level - how this nebulous concept shifts from season to season, person to person - than the revolutionary couturier Coco Chanel. From the 20th century’s early years to her death in 1971, her career responded to (and even steered) major changes in notions of female beauty.

She freed women from corsets in the 1910s and replaced fussy frills with the little black dress in the 20s; she played with gender, getting women into sailor tops and trousers; she turned comfy jersey into day wear not just underwear; she made suntans desirable. The list goes on. One of her famed definitions of beauty reflects the massive upheaval in women’s identity, from the Suffragettes to the 60s women’s movement, prizing individuality and uniqueness over passive conformity: “Beauty begins the moment you decide to be yourself,” she said - an idea that continues to play out today.

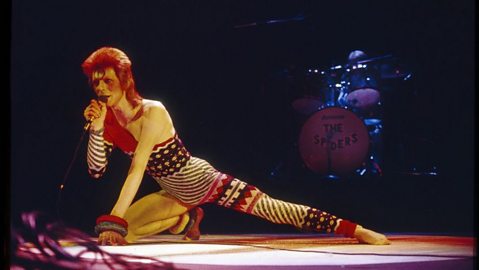

6. Bowie: beauty is strange

An Introduction to Ziggy...

How David Bowie arrived at one of the most iconic creations in pop history.

That beauty should do something out of the ordinary is an idea that has appealed to creative minds as diverse as gothic mystery writer Edgar Allen Poe (“There is no exquisite beauty… without some strangeness in the proportion”) and snowy-quiffed fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld (“I don’t like standard beauty - there is no beauty without strangeness”).

The 20th century master of the form was . “Turn and face the strange,” he sang in Changes. Indeed, throughout his career he reinvented his look, using non-conformist beauty as a kind of social commentary. Androgyny was his key tool, from the album art of The Man Who Sold the World, where he appears as a card-playing courtesan in a dress and flowing long hair reportedly inspired by a Pre-Raphaelite painting, to Ziggy Stardust’s red bouffant possibly inspired by Kabuki theatre, or the streak of lightening that zips across his delicate features as Aladdin Sane.

Bowie’s approach to personal beauty might superficially seem of a piece with Chanel’s call to self-expression. Yet his constant play with identity was just the opposite: a celebration of surface fakery where beauty is as malleable as a tub of sparkly face paint.

7. Aguilera: beauty is inside you

“I am beautiful no matter what they say, words can’t bring me down”, asserts in her 2003 torch song to herself, Beautiful. It’s no mere ‘me culture’ ballad though. With its themes of conquering insecurity in the face of others’ prejudice, Aguilera’s Beautiful was a huge hit with the gay community and was named the 00’s most empowering LGBT anthem by the charity Stonewall in 2011.

Aguilera’s message certainly resonates. The song’s been covered by everyone from indie-rockers to post-punk legend . Meanwhile, inner beauty has since become a whole sub-genre for pop songs that tackle identity politics, from ’ Superwoman to ’s Born This Way.

8. Miss Piggy: beauty is worth fighting for

Today we think of beauty as subjective, even when it comes to the most apparently gorgeous members of a society. That doesn’t mean we have to take anyone else’s opinion lying down. One feminist firebrand who has brought her signature punchy wit to the issue is Miss Piggy: “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and it may be necessary from time to time to give a stupid or misinformed beholder a black eye.”