DAN SNOW:Hello, I'm Dan Snow. When thinking about the causalities of World War One the sort of images that first come to mind are those of the trenches, poppy fields and the graves marked out in the former battlefields of France and Belgium. Many of course survived those horrors, but to do so could end up being a horror in itself.

DAN SNOW:Doctors were unable to do much to stop the pain for tens of thousands of amputees who came back from the conflict. And they came across huge challenges when dealing with some of the terrible facial injuries that many suffered.

DAN SNOW:But, as I discovered in this clip you're about to see, some of the reconstruction work surgeons pioneered back then it's quite extraordinary.

DAN SNOW:The scale of the First World War is almost unimaginable. In four years, some one million British and Commonwealth soldiers died.

DAN SNOW:But two million men were also wounded during World War One. New weapons systems meant there were terrible new injuries to contend with. And medical science had advanced so that men in who previous wars would have died of their wounds, were now being kept alive. That's what made this war unlike any that had gone before.

DAN SNOW:Light and easily portable machine guns and shrapnel from shells caused terrible suffering. More than 20 thousand soldiers were injured in the face. Many of the wounded came to Queen Mary Hospital in Sidcup. Dr Andrew Bamji, who's based at the hospital, has studied the work of the surgeons who had to deal with facial injuries.

DAN SNOW:So what was causing these terrible wounds?

ANDREW BAMJI:The injury they would get would depend on what had injured them. So if it was a bullet like this, then you'd get a fairly clean, sharp wound. If it was a shell fragment like this, you'd get a huge tearing injury. So you imagine something of this size tearing past at 100 miles per hour and catching you with a sharp corner.

DAN SNOW:These pictures are absolutely shocking - it's impossible to show these on television. But I've never seen such hideous facial injuries.

DAN SNOW:The team at Sidcup were led by Sir Harold Gillies who pioneered new methods of cosmetic surgery. Such as the waltzing tube pedicle a revolutionary technique that vastly improves skin grafts.

ANDREW BAMJI:And of particular interest here, we've got a tube pedicle and it's been taken from this great flap of skin here which has been rolled, sewed up at the edge and then sewn into the cheek here.

DAN SNOW:The new skin joint develops its own blood supply, allowing the original joint to be cut and sewn on elsewhere.

DAN SNOW:So you kind of leap frog skin up the body do you?

ANDREW BAMJI:You can do and that was called the waltzing pedicle. So you could take it from the leg and you could put it onto the tummy and then onto the arm and then onto the face.

DAN SNOW:Techniques like this meant that Gillies could make dramatic transformations in the soldiers faces.

ANDREW BAMJI:So this is a chap called "Bonar" who was in the Highland Light Infantry - 'don't worry about the black that’s the iodine but 'he's lost you can see his lip here and then there are the afterwards 'photographs so that you've got a record of how successful 'the surgery was.

DAN SNOW:It really is remarkable recovery here.

DAN SNOW:The reconstructive surgery was a slow process and the extent of the injuries meant that many of the patients were shunned by members of the public.

DAN SNOW:Here at the hospital, some of the benches were painted blue for use by the disfigured patients and that meant that anyone else sitting down should be aware they might end up next to someone with terrible facial injuries.

DAN SNOW:There was only so much surgeons like Gillies could do. Some patients needed a different approach and that was provided by professor of sculpture, called Francis Derwent Wood. He volunteered as a medical orderly in London and was moved by the suffering of men with awful facial injuries.

DAN SNOW:Wood put his artistic expertise to use to make life-like masks to cover their terrible wounds. They were called portrait masks.

SARAH CRELLIN:There were a vast number of suicides pro rata, in facially mutilated men compared to men with other injuries

SARAH CRELLIN:and he was very distressed by this and felt that a portrait mask might serve in some way to help to protect these men from the world's gaze really.

DAN SNOW:'With typically irreverent military humour, the soldiers called the operation "the tin nose shop." But it was much more sophisticated than this name suggests. Derwent Wood's technique was copied in Paris and at Sidcup, with artists carefully taking moulds - recreating the damaged face and skilfully painting the masks to create a realistic effect.

DAN SNOW:This is an example of the kind of prosthetic face mask that was used during the war to cover up these terrible wounds, and it's the only one that this archive is aware of existing in the entire world. It's absolutely beautiful, this very fine silver is very carefully crafted to follow the contours of the cheek and the jaw bone.

DAN SNOW:And then obviously this is all hand painted and you can see they've tried to match it up with whatever the skin tone was on the surviving skin around here and very cleverly it's held to the face with these glasses that loop over the ears.

DAN SNOW:The work of men like Gillies and Derwent Wood gave dignity and the semblance of a normal life back to men who'd suffered terrible injuries. They could now face the world again.

Video summary

Dan Snow looks at the how facial reconstruction surgery developed in World War One.

New weapons in World War One such as machine guns and artillery fire not only led to the deaths of nearly 1 million men from the British army, but also horrific facial wounds caused by shrapnel.

Harold Gillies developed the tube pedicle to help make skin grafts more successful.

This helped improve blood supply to the new skin and led to dramatic improvements in the facial appearance of injured soldiers.

Francis Derwent Wood helped develop life like masks called portrait masks to help soldiers deal with the mental trauma of their facial injuries.

These prosthetic masks helped give wounded soldiers a chance to return to normality.

This clip contains disturbing scenes. Teacher review is recommended prior to use in class.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 4 / GCSE:

Students could be asked to list all of the developments in surgery that had happened prior to World War One and examples they can think of war improving surgery.

Then they could watch the clip and explain how the events of World War One allowed surgery to improve and helped Gilies and Derwent Wood to make their discoveries.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS4/GCSE in England Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at National 4/National 5 and Higher in Scotland.

How challenging was the life of a pilot in World War One? video

James May looks at the dangers and challenges facing pilots in World War One.

What were trench conditions like in World War One? video

Saul David looks at how British soldiers coped with trench conditions in World War One

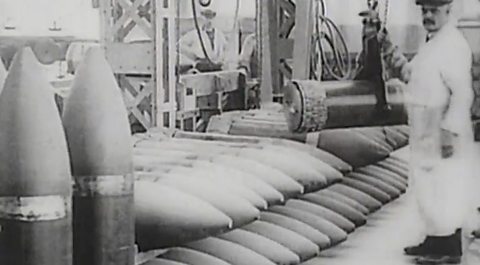

How did Britain meet demands for weapon production in World War One? video

Saul David on how Britain struggled to produce the weapons to supply the army in World War One.