DAN SNOW:Hello, I'm Dan Snow. World War One was a conflict on an industrial scale. A massive operation that provided many, many lessons for the future on what would and wouldn't work in modern warfare.

DAN SNOW:Technological developments, especially in weapons, we're being made all the time. A situation the armed forces will be familiar with even today.

DAN SNOW:Between 1914 and 1918, things reached a point where the generals and the soldiers on the ground just couldn’t keep up. And as Saul David explains in this next clip, the huge human cost was being matched by a gigantic financial bill that was going up all the time.

SAUL DAVID:'At its peak in the winter of 1917-18, the war was costing Britain 'the equivalent in today's money more than £20 million an hour. 'That’s over £3 billion every single week. 'Week after week after week.

SAUL DAVID:'That money was going on transport and supply and food and wages. 'But much of it was also literally going up in smoke.'

SAUL DAVID:That’s extraordinary! I mean you really get a sense that you've got a powerful killing machine in your hands here and it seems to be accurate too. The sandbag is literally obliterated in the exact spot I was aiming at.

SAUL DAVID:But here's the problem, because this gun fires 600 rounds a minute, that’s 10 a second, and it literally is firing more bullets than could be made to supply it.

SAUL DAVID:'Automatically feeding ammunition, the Vickers machine gun 'used up bullets at the same rate as 80 conventional rifles. 'And it wasn’t just machine guns.

SAUL DAVID:'As the warring sides dug in, more artillery pieces were used 'with ever bigger calibres 'in a disparate bid to break the deadlock.'

SAUL DAVID:'In March 1915 at The Battle of Neuve Chapelle, 'more shells were fired in the initial brief bombardment 'than during the entire Boer War. 'And the biggest problem was that munitions were being used faster 'than they could be made.

SAUL DAVID:'Britain had enough guns but it was fast running out of anything 'to actually fire.' By the spring of 1915, so serious was the so called "shell crisis" that most British guns had been reduced to firing just four shells a day.

SAUL DAVID:And it seemed as if the war might be lost - not in the trenches of Flanders but in the factories of Britain. 'It was nothing short of a scandal, 'resulting in the formation of a coalition government 'and the establishment of a new government department - 'the Ministry of Munitions.

SAUL DAVID:'It was estimated that the Allies needed to produce 'nearly two million artillery shells a week. 'British factories were producing just 11,000. 'The new ministry set about building munitions factories, 'transforming a civilian economy to one completely geared towards war.

SAUL DAVID:'Here at Holton Heath in Dorset 'are the remains of one of those factories. 'It was built in 1915 to make cordite, 'the explosive that propelled bullets and shells.'

SAUL DAVID:So we're just here, on the edge of the service reservoir and if you just get a look around us, this whole concreted area here is the service reservoir. And yet on map, it's just a tiny piece at the centre of this massive factory.

SAUL DAVID:It covered 500 acres and employed more than 5,000 people and the reason it was sited here, on Holton Heath, was because of two key things.

SAUL DAVID:One - the rail link. The Sothern railway line ran directly through here so you've got a spur into the factory, and two - the water links.

SAUL DAVID:You can see this channel coming out of Poole Harbour, right to the doorstep. It had its own docks. 'Not much of the original factory remains, 'this is the first kind of sense I've got of the sheer magnitude 'of this operation and its importance.'

SAUL DAVID:This is bricks and mortar, this was Britain's war effort. And this was just one small part of it, you can just imagine the reek of this place.

SAUL DAVID:'A key constituent of cordite was a chemical called acetone. 'Before the war, Britain imported most of it from Germany. 'But this was now clearly impossible.'

2100:05:22:20 00:05:37:07SAUL DAVID:Unable to produce acetone in any quantity, cordite production was crippled, and without cordite all British guns, from the Lee-Enfield to the artillery, were mere metal pipes. 'It was potentially a fatal blow to the war effort.

SAUL DAVID:'The newly created Ministry of Munitions needed to find 'a different source.

SAUL DAVID:Enter this man, Chaim Weizmann. A professor at the University of Manchester and a brilliant Biochemist. Using grain and maize as raw materials, Weizmann found that he could produce acetone in large quantities, and this huge concrete vat behind me, almost a hundred years old, is what he actually used in the fermentation process.

SAUL DAVID:'But Weizmann's new way of producing acetone soon ran into problems. 'Grain and maize were also in short supply as they were needed 'to feed the civilian population.'

SAUL DAVID:I suppose its typically British, the solution to this second acetone crisis, because instead of turning to some wonderful, chemical compound they turned to this. The ordinary British conker.

SAUL DAVID:Now tests have been shown that this could be fermented into acetone and so the British government asked schoolchildren across the country to go out and gather these.

SAUL DAVID:Not for fun, not for playing conkers in the school yard, but for vital munitions work. And it’s extraordinary to think that this… powered this.

SAUL DAVID:'Weizmann's solution to acetone shortage was so successful 'that from 1917, the British Empire was able to supply more than '50 million shells a year and billions of bullets 'to the front line. 'A century later, many still lie in the fields of France and Belgium.'

Video summary

World War One was costing the equivalent of £20 million an hour in today's money, on transport, supplies and weapons.

Machine guns were firing more bullets than could be made to supply them.

Britain had enough guns but was struggling to meet demand for bullets and shells.

In 1915 the government created a munitions ministry.

2 million artillery shells were needed per week, but only 11,000 were being produced.

New munitions factories were quickly opened.

Saul David visits the remains of an explosives factory at Holton Heath where 5,000 people were employed to make cordite.

Chaim Weizmann found new ways of producing acetone from conkers to help with production, which by 1917 succeeded in supplying 15 million shells a year to the front line.

Teacher Notes

This could be used as part of a lesson about total war.

The phrase ‘Total War’ and a definition could be put on the board and students could then be asked to think of all the people who could have been involved in this.

Then they could watch the clip and write down the challenges Britain faced in meeting demand for munitions supplies.

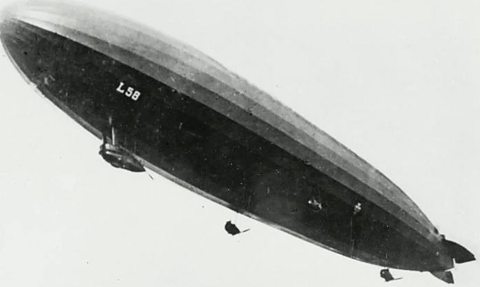

They could look into other aspects of life in Britain during the war and compare munitions production with other areas (such as rationing, the Zeppelin threat) and explain which they think had the biggest impact on peoples lives.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at 3rd Level, 4th Level, National 4/National 5 and Higher in Scotland.

Suffragettes - Did the status of women change after World War One? video

Kate Adie considers the legacy of World War One on women’s rights in Britain.

How did Britain deal with the Zeppelin threat during World War One? video

Ben Robinson examines the Zeppelin threat to Britain during World War One.

How did facial reconstructive surgery develop in World War One? video

Dan Snow looks at how facial reconstruction surgery developed in World War One.