Dan Snow:Hello, I'm Dan Snow. When we look back at World War One, the trenches are among the first things that come to mind. Those scars on the battlefield that played such a key role in the conflict, sometimes giving men the security and safety they wanted and sometimes leaving them feeling trapped like rats in a disease-ridden hole.

Dan Snow:When the war ended, life in the trenches was captured again and again in poems, novels, art and later films, all of which powerfully put across the horrible conditions soldiers experienced.

Dan Snow:You can of course visit the sites and get a sense of the experience today, which is what military historian, Saul David, does in this next clip. Looking at how the best way to get through things was to find a buddy and watch each other's backs.

Saul David:So how do we do this?

David Kenyon:Simplest thing… reach across and your see there's those two bars half way down.

Saul David:David Kenyon is a battlefield archaeologist who spent seven years excavating the trenches of Thiepval on the Somme.

David Kenyon:You get a bit of a feel for what it's like actually in the trench itself.

Saul David:Yeah it's pretty narrow is that deliberate?

David Kenyon:It is deliberate yes, it's-- protects you from overhead explosions and shrapnel and all that kind of thing. If it were wider you'd be more vulnerable, so.

Saul David:And a little bit of duckboard here to keep the feet dry, how significant is that?

David Kenyon:Yes, that's actually covering a sump in the floor there, there's a hole, square hole about that deep it goes down there with the duckboard over the top. And that would have acted as a drain, water flowing down the trench would have collected in there.

Saul David:Just as in Henry V's day, dysentery was once more a major problem. But there was another ubiquitous condition, trench foot, that could lead to gangrene and amputation.

David Kenyon:Ideally every 24 hours, men are getting fresh socks. And you don't get a choice, it's compulsory. You have to get your boots off, you have to look at your feet, you have to dry your feet thoroughly and you have to get some clean socks on.

David Kenyon:And if you and I were in a trench together, they had a sort of pairing system where we'd be matched into pairs and I'm responsible for your feet and you're responsible for mine. Because If you're cold and wet and tired, taking your puttee and boots off is a bit of a palava and you might not feel like it, so you'll go, "Oh, I'll do it tomorrow."

David Kenyon:But if I'm responsible for your feet, I'm going to make you do it and vice versa.

Saul David:The risk of losing men to disease, possibly even the entire war, prompted the army to take hygiene more seriously than ever before.

David Kenyon:This here is the 1912 "Manual of Elementary Military Hygiene" and this is a pre-war publication, this is them getting ready for the next war whenever it should happen.

David Kenyon:And you can see it's really detailed we've got cause of disease, all sorts of different diseases listed there; Cholera, Dysentery, Malaria and then how to deal with it essentially, so.

Saul David:Yeah, prevention.

David Kenyon:Sorting out your water supply, how to handle your food, physical training, its gone from being… well, not quite optional, but something that’s done ad hoc to something that’s absolutely embedded within the system and it's enforced by military law and military discipline.

Saul David:Living in stagnant, rat-infested trenches, each man's personal wash kit was as essential to his survival as his rifle.

David Kenyon:We found a groundsheet and wrapped up inside that groundsheet was a soldier's wash kit essentially, everything he needed to look after himself here in the trench. Some of these things you'll recognise, that’s his toothbrush.

Saul David:Minus its bristles, but it's pretty clear isn't it?

David Kenyon:Then… another everyday activity, that's a shaving brush.

Saul David:A few bristles still intact.

David Kenyon:I think the way it was designed to work is that you take that bit off and plug it on the bottom and it becomes the handle.

Saul David:Oh I see.

David Kenyon:And to go with it we have shaving soap.

Saul David:Complete with the name, it still reads–

David Kenyon:The maker's name yes.

Saul David:"Finlay's shaving soap, established Belfast, Ireland."

David Kenyon:It's quite possible that this survived in the trench here because its owner - some misfortune befell him and he never came back for it. And then the other daily necessity.

Saul David:Reading matter?

David Kenyon:Er, not necessarily. It's actually a religious tract. It has the words of hymns and things like that on it, I don’t think he was planning to read it.

Saul David:Toilet paper?

David Kenyon:Toilet paper yes.Saul David:[LAUGHS]

Saul David:So he's going to take it from where he can get it, is he?

David Kenyon:Oh yes absolutely, anything suitable was carefully rounded up and stored.

Saul David:Thin enough and absorbent enough.

David Kenyon:So if some religious type was in the rear issuing pamphlets out, he would have had a very ready audience for them but probably not for what he intended them for.

Saul David:So David does this find change the way we think about hygiene in the trenches in the First World War?

David Kenyon:Well what It does is is it confirms what was going on because we know we have official pamphlets that say that this is what the army wanted to do. And instructions saying that this is what should be done.

David Kenyon:But finding something like this bang in the front line, shows that it really was being done. It's proof that the soldiers were carrying out their instructions, which you wouldn't get from other sources, so it is pretty important.

Video summary

Saul David looks at the excavation of trenches near Thiepval in France.

He looks at the effects of trench foot on soldiers and how they worked in pairs to look after each other’s feet.

The army took hygiene seriously to make sure soldiers were fit to fight.

He looks at a soldier’s wash kit that was essential in looking after themselves.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3 / Key Stage 4:

Students could be shown a picture of a flooded trench in World War One.

In pairs they could annotate the picture using their prior knowledge of trench design to explain the possible causes of the flooding and why conditions were so poor.

Then they could add ideas about how soldiers could best look after themselves in such conditions.

Then when they have watched the clip they could add further ideas to the picture to explain what soldiers actually did to try and protect themselves.

This clip will be relevant for teaching History at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at 3rd Level, 4th Level, National 4/National 5 and Higher in Scotland.

What was agreed at the Treaty of Versailles? video

Dan Snow looks at the terms and consequences of the Treaty of Versailles.

What was the contribution of Indian Sikhs in World War One? video

A closer look at how Indian Sikhs played a key role in the British army during World War One.

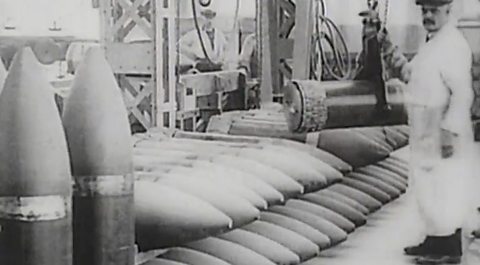

How did Britain meet demands for weapon production in World War One? video

Saul David on how Britain struggled to produce the weapons to supply the army in World War One.