How not to be a Victorian woman

-

![]()

Helen shares what she learned from In Our Time.

Being society’s idea of a “perfect woman” involves a huge amount of admin. It's not just the debilitating grooming regimen, there’s the pushing out of babies, bringing them up and holding down a job. There’s the relentless apologising and the giggling at patently unfunny jokes told by men. It’s a full-time job.

So consider, if you will, Victorian woman, and the insane constraints placed upon her. If in 2017 the ideal woman is expected to stay quiet in a meeting lest she be labeled “bossy”, our Victorian counterpart was supposed to remain fully covered, fully restrained, basically silent and fairly ignorant.

Elizabeth Gaskell and her 1855 novel show the dos and do-not-do-under-any-circumstances of being a respectable woman in the 19th century.

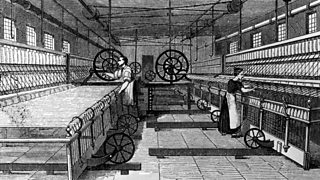

Her coming-of-age involved understanding how society treated women, and also seeing the grinding poverty of the industrial North after leaving her childhood home in Cheshire. She saw people starving, being forced to live in cellars, working for often cruel factory owners. And then she wrote it down. As a reward, Gaskell was derided by some critics at the time for being a “woman who tried to be a man.”

Don’t be too clever

So I suppose the first “don’t-do” for Victorian women is “be well educated”. Some critics said Gaskell was a woman who tried to be a man because she was writing in a frank way about the world around her.

The fact that she'd been born into a Unitarian family made all the difference to Gaskell’s career – she was part of a small group of people born with the xx chromosome who were really able to show what life was like for them. Unitarians believed that women should be educated and given the opportunity to be active in the world.

Gaskell’s husband William was supportive of her work as a writer, which involved going to meet people across the country, and this had a huge impact. He encouraged her to write her first novel, Mary Barton. This was is at a time when universities such as Oxford and Cambridge would not admit women.

Keep your hair a state secret

The next “don’t” is remove your bonnet. For the love of God, keep that thing on your head!

In Gaskell’s North and South, the protagonist Margaret Hale, who leaves rural Hampshire for the fictitious city of Milton (aka Manchester) becomes embroiled in the struggle between a mill owner and his workers. She also takes off her bonnet and lets her hair hang loose when speaking to workers, which was seen as quite sexual behaviour.

"Women always had their bonnets on!"

Sally Shuttleworth talks about a controversial scene in Gaskell's novel, North And South.

Feeling passionate? Just stop it!

Margaret finds herself in a dramatic mood and decides to throw herself before proud factory owner Mr Thornton in front of a crowd. She is seen to have disgraced herself. But then, at that point, even to have a woman talking on a platform was seen as unfeminine and shameful.

Here’s a fun game – imagine what the 1850s take on pretty much anything a woman does or says in 2017 would be. Your jeans, your hair, your qualifications. In the 1850s, you’re a rebel.

Don’t question anything, ever

Another rule for respectable Victorian woman was “don’t rock the boat”, which Gaskell did. She was subversive at the time in terms of gender, and the force and energy of her character Margaret highlights the very few things women were supposed to do at the time. The way she takes charge of life around her makes her the exception to the rule.

Well-behaved women seldom make history

The same could be said of Gaskell, who challenged the idea of social rank by giving female characters authority, but also by giving working people standing as well as authority. Gaskell in particular shows them to be intelligent, articulate, courageous human beings. In fact, she was seen as so subversive that her later novel Ruth was burnt by some for being too shocking.

However, while Gaskell doesn’t instruct us how to be respectable Victorian women, her lack of respectability teaches us something about how to be remembered.

She was later published under the name “Mrs Gaskell” which was a turn-off because it made her sound too safe, and she faded from relevance. Later critics derided her for being “feminine”, but her legacy was salvaged in the 60s and 70s by people who didn’t see that as a bad thing.