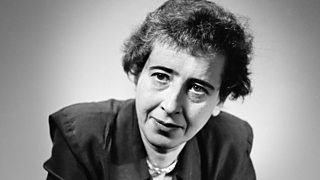

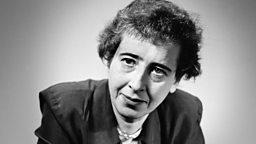

What Hannah Arendt can teach us about totalitarianism

-

![]()

Helen shares what she learned from In Our Time.

was a political thinker who understood fascism better than many. She was right there, eye-to-eye with the beast.

Arendt was born near Hanover, Germany, in 1906. Her family was secular-Jewish and she said she first heard the word "Jew” when children shouted anti-Semitic phrases at her while she was playing outside. If that wasn’t enough exposure to racism, Arendt also had a long-standing love affair with philosopher Martin Heidegger who later became a Nazi.

Hannah Arendt is newly popular – her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, has been flying off the shelves. I have to confess that beyond “the banality of evil” I couldn’t quote her at all and, like many others, had never read any of her books. But people are becoming more interested in her – me included.

Arendt has become most famous for her exploration of totalitarianism and her analysis of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, who was one of the chief architects of the Holocaust. It was for this trial and this man that she used the phrase “the banality of evil” so effectively.

Arendt believed that a society in which individuals are disconnected from each other is most vulnerable to totalitarian leaders.

“When people are atomized, a movement or a strongman arises and he offers a story or an ideology which claims to explain everything, why people are unhappy,” explained ’s guest Robert Eaglestone. “This story becomes more and more powerful. You can’t argue with people who become Nazis or Stalinists because there’s only one way to think.”

Arendt’s other key idea about totalitarianism was something she called “terror”.

“Totalitarian terror regimes take away your name, your identity, your rights and reduce you to just your body,” said Eaglestone. Arendt thought that once you’re just a body you’re superfluous and you can be killed without the killer feeling any guilt.

The two main ideas in The Origins of Totalitarianism

Robert Eaglestone explains how Hannah Arendt summed up the essence of totalitarianism.

Arendt’s refugee status made her an expert in how society must function because she was outside it. She left Europe via a French internment camp and settled in the USA on a refugee visa. Once there she felt out of place, not least because of the American insistence on standing outside to smoke, which appalled her as it would any good mid-century intellectual.

Her “refugee” label was even more appalling to her than having to take her cigarettes outside – she did not like being tied in with the USA’s huddled masses. “Refugee” is a stripping away of truthful identity, and Arendt wrote about being made a “pariah” in her essay, We Refugees.

When Arendt wrote about "the banality of evil", she didn’t mean that the horrors of the Holocaust were banal – far from it. It was a commentary on how evil had been normalised. Mass murder had become routine and Adolf Eichmann embodied this banality; he was bureaucratic and had no inner dialogue over right and wrong.

Arendt wanted to strip fascism of its super-Satan image. However, Eichmann’s trial was the first time that many Holocaust survivors spoke about what they’d lived through. “The banality of evil” may almost have been reduced to a bumper-sticker truism now, but in the 1960s people greeted it with horror.

Arendt believed that evil isn’t its own thing but a privation of goodness, and that there’s a difference between the do-er and the deed. But she did believe that totalitarianism would resurface – a fungus that infected the brains of isolated people; rootless but hard to kill.