Kathak: Does every gesture have a meaning?

Performer, choreographer and writer Chitra Sundaram writes for 91热爆 Arts about the history of Kathak dance.

Indian dance does want to tell stories; but, ultimately, emotion and spirit is what all classical Indian dance cares deeply about.

Kathak is the one classical Indian dance that has a singular DNA

Each ‘style’ (as in ‘Bharatanatyam’ and ‘Kathak’ featured in 91热爆 Young Dancer) has its demanding, characteristic physical vocabulary and repertoire to express this.

But all share a common, dance-theatre heritage that seems to need not only to joyously dance but also to tell stories, about gods and their exploits, what they do in their fanciful realm - and on earth - to their fans and foes!

That said, of all the classical Indian dances, Kathak is the one that is especially introduced as ‘a storytelling dance’.

The name ‘Kathak’ is derived from the Sanskrit word Katha or ‘story’ and from Katthaka or ‘storyteller’, referred to in ancient and medieval Indian literature.

But ‘storytelling’ and temples though its origin may be, Kathak is the one dance that has a singular DNA, as it were.

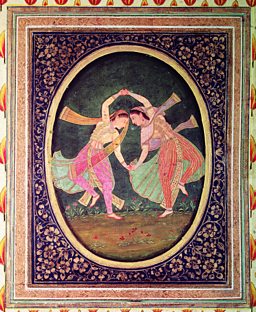

An impulse to dazzle us most, with its heart-stopping bursts of rhythmic virtuosity, and to enchant with its delicate, lyrical exploration of romantic, as well as devotional, poetry.

One special period of a history of repeated invasions of India sets it apart from the multitude of classical Indian dances: Kathak is the only Indian dance form to have been directly and deeply impacted by the arrival and rule of northern and central India by the .

Thus, Kathak is legitimately both Hindu and Islamic, and unique in having a historical link to a religion that pretty much ‘officially’ forbids dance and music! To my mind, that would make Kathak an ‘activist’ dance-form, just by its practice!

In fact, the inimitably exquisite Kathak dancer Nahid Siddiqui, settled and nurtured in the UK, has a hard time practising and presenting her art in her birth-country of Pakistan.

The same would be true of UK’s Kathak-trained Contemporary Dance god, the prodigiously talented Akram Khan, were he to return to perform in Bangladesh, the country of his parents’ birth.

The delightful Sonia Sabri showcases Kathak as an exemplary British Dance artist in the capitals of Europe.

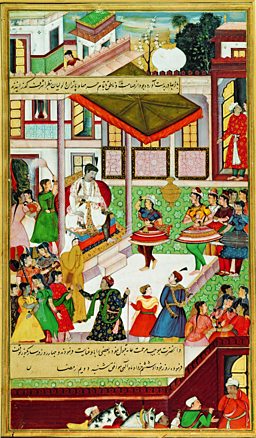

Yet there was a historically significant time when art and culture, and poetry, music and dance of ancient and ‘Golden Age’ India flourished in Hindu kingdoms down south, as in the Mughal courts, especially during the time of Emperor Akbar ‘the Great’ (1542-1605). He was a true coalition builder who reputedly took a Hindu princess as wife.

The influence of the Mughal court, with their whirling female dancers imported from Persia and Central Europe, are credited with making Kathak visibly, immediately and freeingly different from the other earth-bound, ‘demi-plié’-d, religious storytelling, Indian classical dance forms: Kathak became the court dance par excellence, erect, elegant, secularised and sophisticated!

Dance practitioner families went underground - or gave up - to survive societal censure as recently as the 20th century

But all classical dances from India have a fragmented history: hereditary dance practitioner families went underground - or gave up - to survive a legal ban on performance and societal censure as recently as the 20th century: no more temple dancing, no royal courts for courtesans to exhibit their craft in, and no professional venues either – not until India gained independence.

As we see it now, Kathak, whether from the Jaipur or the Lucknow tradition, spins us a gossamer tale of two cultures, with the romance of lyrical movement to poetic sentiment studded by a steely physical virtuosity of spins and rhythmic calculations, and footwork patterns that announce Kathak’s links to Flamenco – all arriving magically, after complex excursions, at the rhythmic cycle count of ‘one’ or sum! But that’s another journey, for another time!

Meanwhile we can go on sparkling Kathak journeys right here in Britain: Pratap Pawar, the guru of Akram Khan (and a 91热爆 Young Dancer Judge), has been teaching Kathak in the UK and internationally for over 50 years.

Pratap-ji’s guru, the unrivalled, ageless Birju Maharaj comes from a centuries-old family of hereditary court musicians and dancers, and entrances fans in the UK and around the world.

There is also well-known teacher Sujata Banerjee, whose student Vidya Patel is a 91热爆 Young Dancer finalist, and who is newly choreographed by Urja Desai, a disciple of the legendary Kumudini Lakhia, who pretty much ‘invented’ a modern, ensemble body of work for Kathak.

And there is the South Bank Centre’s Associate Artist Gauri Sharma, whose disciples appear as ‘Ankh Dance Company’ in May at SBC’s Alchemy, as does the superb Aditi Mangaldas from India, a fitting heir to Lakhia’s modernity. And Aakash Odedra (91热爆 Young Dancer Judge and Mentor) is UK’s rising dance star who takes Kathak and its contemporary interpretations into different orbits! Enjoy the ride!

91热爆 Young Dancer 2015

-

![]()

Five finalists perform two solos and a duet for a place in the Grand Final