How Austen went from family teatime viewing to steamy primetime blockbuster

10 July 2017

It is a truth universally acknowledged that television history was made when Colin Firth's brooding Mr Darcy emerged dripping wet from Pemberley's lake in the 1995 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. Professor KATHRYN SUTHERLAND, lead academic on the Jane Austen bicentenary celebrations, gives a historical perspective on the long relationship between Austen and the 91热爆.

By Professor Kathryn Sutherland

The 91热爆's flirtation with Jane Austen started very early on in the broadcaster's history. Only two years after the 91热爆 began in 1922 short extracts from Pride and Prejudice became the first of the author's works to be heard on the radio. It was the beginning of a long, fruitful and ever-changing relationship.

Television started in 1936, much earlier than people surmise, as the 91热爆 launched the world’s first hi-definition television service with an ambitious programme of drama, dance and entertainment shows. Again, just two years later in 1938 those in charge of Auntie turned to Jane Austen's famous romance and Pride and Prejudice was the first book chosen to be brought to screens.

Those early television adaptations were inspired by radio dramatisations, obeying the same principles of fidelity to the original written work and a reliance on dialogue. They carried over techniques from the stage: artificial indoor sets with little or no outdoor action or naturalistic settings.

Sadly, as television was in its infancy and film was eye-wateringly expensive the production has not survived in the archives. But we know that cameras were fixed and shots were dominated by close ups of talking heads. Sensory effects were subordinated to a consciously theatrical dialogue and period-style aesthetic distance.

Fast forward almost thirty years and the creative approach hadn't significantly moved on. As you can see from this clip from 1967, Sylvia Coleridge as the hoity Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Celia Bannerman in the lead role of headstrong Miss Bennet give theatrical performances with little movement, while camera shots are closely focused on the face.

Pride and Prejudice (1967)

Celia Bannerman as Elizabeth Bennet opposite Sylvia Coleridge's Lady Catherine de Bourgh

What now appears most obviously missing is the energy we associate with moving cameras, quick cuts, the openness of outdoor location filming and the intensity of a strong musical score – all features that currently identify classic novel adaptations for large and small screen. The 1980 91热爆 mini-series Pride and Prejudice, directed by Cyril Coke and with a screenplay by Fay Weldon and featuring Call the Midwife's Judy Parfitt as Darcy's acerbic aunt, marked the emergence of this newer mode.

With the shift away from television’s parceling of high literature as tea-time instruction, there was a shift, too, in how we understand Austen’s style of romance, away from love as reward for the heroine’s moral education towards an open celebration of what has been called ‘real estate fiction’ (Marjorie Garber, ‘The Jane Austen Syndrome’, 2003).

The rebranding of Austen’s novels as ‘real estate fiction’ is one obvious consequence of filming in outdoor locations, shifting the heritage values we have always associated with her novels towards a celebration of Britain as tourist destination; still heritage, but with a different consumerist spin.

Pride and Prejudice (1980)

Elizabeth Garvie as Ms Bennet and Judy Parfitt plays Lady Catherine de Bourgh

Then there is the hero. It wasn’t until recent adaptations that we gave much thought to Austen’s hero as anything more than an instructor or a moral ideal. But now, thanks to Andrew Davies’s game-changing 91热爆 miniseries of 1995 Pride and Prejudice, the hero has a body, physical and emotional expressiveness: he fences, swims, boxes, strips off, bathes, and he smoulders.

We all know him to be a proud, unpleasant sort of man; but this would be nothing if you really liked him.Pride and Prejudice

Our present day recognition of Austen as romantic novelist lies in such powerful imagery. It presents problems, of course: what is rendered ambivalent in the novels (the hero’s ultimate importance in the heroine’s maturing and her wider relations with society) is now shorn of almost all complexity. Such tunneled vision jettisons the sophisticated system of manipulative social relations in which the novels trade, to be replaced by more exclusive focus on the marriage or rather the sex plot.

Contemporary rebranding

Film is not novel; yet its promotional energy and interpretative agency are now impossible to disentangle from an understanding of Austen’s novels. Current adaptations are part of her rebranding as the godmother of twenty-first-century romance. This Jane Austen is not what she once was: a writer of impeccable eighteenth-century credentials, barbed wit, and complex morality; now she is savvy, sexy and very modern. She is poised, too, for cross-species and extra-terrestrial conquests. Mash ups like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) promise a new spin on Austen’s codified societies; or rather, the fun that comes from crashing one set of established genre codes against another.

Film authenticates its own activity by drawing out what is subject to adaptation in the original and by questioning and reconfiguring ideas of property in the text. Over the last 100 years adaptation has broken through so many barriers: where will it all end?

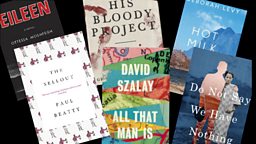

Pride and Prejudice (1995)

Jennifer Ehle plays Elizabeth Bennet and Barbara Leigh-Hunt as Lady Catherine de Bourgh

Austen and the silver screen

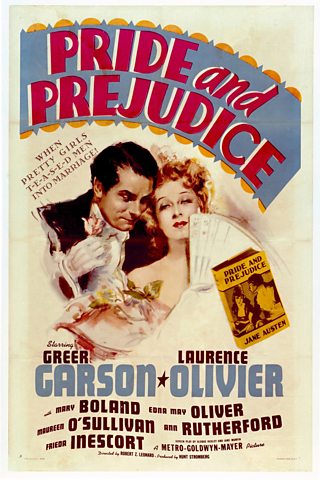

Jane Austen’s Hollywood breakthrough came in 1940 with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s film of Pride and Prejudice, starring Laurence Olivier as Mr Darcy and Greer Garson as Elizabeth Bennet. There were no further big-screen versions before the mid-1990s. Her intimate and thrifty novels were long understood as more appropriate to home entertainment and domestic instruction: afternoon readings for radio and tea-time adaptations for television. Both forms were long the cultural domain of the 91热爆. Its early interpretations of Austen were, in turn, indebted to the illustrated editions of the novels marketed from the 1890s.

The illustrator Hugh Thomson’s skilful Cranfordization, as it was known at the time, of the novels, through Regency details of costume and setting, established an easy familiarity with the manners of what we long took to be Jane Austen’s world. Thomson’s illustrations, directed at the adult reader, were instructive of the costumes and gestures, the talking heads, and indoor sets of stage and television productions deep into the twentieth century.

They suggested that the illusion of life her novels offer is composed of small period detail rather than romantic intrigues: ‘dances and card parties and picnics, and young blokes going off to London on horseback for hair cuts and shaves’. These are the words of Humberstall, the central figure in Kipling’s extraordinary short story The Janeites of 1924—a story that describes how reading Jane Austen (I am quite sure in illustrated editions) saved lives in the trenches of Northern France during the Great War. This cosy, Cranfordized image is the version of Jane Austen broadcast in the early years of 91热爆 radio and up to 1950: Austen as solace in difficult times; these were wartime years.

-

![]()

Prepare to be dazzled by Austen's modern-day superfans

Kathryn Sutherland is Professor of English Literature, University of Oxford, and the curator of major national exhibitions around the Jane Austen Bi-Centenary in Winchester and Oxford