The Eyes of Orson Welles

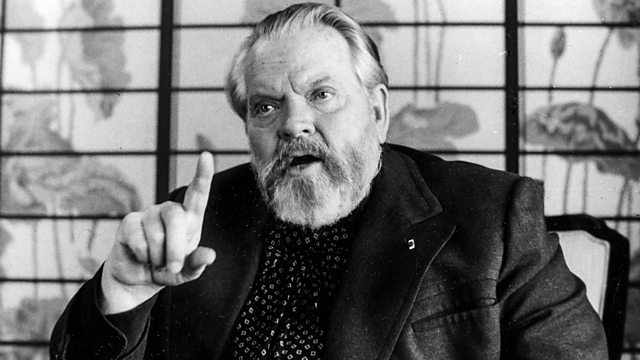

Mark Cousins dives deep into the private drawings and paintings of Orson Welles to shine new light on the passions, politics and imagination of this 20th-century genius.

Granted exclusive access to hundreds of drawings and paintings by Orson Welles, film-maker Mark Cousins dives deep into the visual world of this legendary director and actor, to reveal a portrait of the artist as he’s never been seen before – through his own eyes, sketched by his own hand, painted with his own brush. Executive produced by Michael Moore, The Eyes of Orson Welles brings vividly to life the passions, politics and power of this 20th-century showman and explores how the genius of Welles still resonates today, more than 30 years after his death.

Welles was one of the great creative figures of the 20th century. But one aspect of his life and art has never been discussed. Like Akira Kurosawa and Sergei Eisenstein, Welles loved to draw and paint. As a child prodigy, he trained as an artist, before a drawing trip to Ireland in his teens led to his sensational stage debut at Dublin’s Gate Theatre. Welles continued to draw and paint throughout his life, and his groundbreaking film and theatre work was profoundly shaped by his graphic imagination.

When he died over 30 years ago, he left behind hundreds of character sketches, set designs, visualisations of unmade projects, illustrations to entertain his children and friends, images in the margins of personal letters, and portraits of the people and places that inspired him. They are a window on to the world of Welles, and a vivid illustration of his creativity and visual thinking. Most of these have never been made public. Now, for the first time, Welles’s daughter Beatrice has granted Mark Cousins access to this treasure trove of imagery, to make a film about what he finds there.

The Eyes of Orson Welles is a cinematic essay which avoids the techniques of conventional TV documentaries. It combines Cousins’s trademark commentary with new digital scans and specially made animations of the artworks, which bring vividly to life the magic of Welles’s graphic world. These are intercut with clips from Welles’s films, recordings of his radio performances and TV interviews, and encounters with Beatrice Welles, telling the personal stories of the images. An original score by young Northern Irish composer Matt Regan gives the film emotion and expressivity. The title music is Albinoni’s famous Adagio, a nod to the fact that Welles was the first film-maker to use this in a movie soundtrack, in his 1961 adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial.

The film is told in three central acts – Pawn, Knight and King – with an epilogue on the theme of Jester. The Pawn sequence looks at Welles’s politics, his sympathy with ordinary people, those images that deal with the modesty of human beings – children, decent people who are not in positions of power. The Knight section looks at Welles's obsession with love, his romances with the likes of Dolores del Rio and Rita Hayworth, and his quixotic attachment to what he himself saw as outmoded chivalric ideals. The King section looks at Welles’s fascination with power and its corruption, through illustrations that deal with figures such as Macbeth, Henry V, Kane and Welles himself – the epic mode of human beings, the lawmakers and abusers. The Jester epilogue explores the images that are about fun or mockery, with a surprising intervention by Welles himself.

Cousins also travels to key locations in Welles’s life – New York, Chicago, Kenosha, Arizona, Los Angeles, Spain, Italy, Morocco, Ireland – to capture beautiful images and locate the artworks, and serve to dramatise some of the defining moments in Welles’s career and personal life.

Mark shot the film with two handheld cameras, one a conventional HD camera and one a 4K camera which gives a new Steadicam style of tracking shot without the need for tracks and dolly. It’s the sort of technology that Welles would have loved and could only have dreamed of as he spent a lifetime wrestling with the creative and financial limitations of traditional film-making techniques. This shooting style reflects the immediacy of Welles’s sketches and paintings in their swift engagement with the visual world. These cameras are like Mark’s paintbrushes, giving him a direct, personal and tactile contact between his hand and the captured/created image, without the intermediation of cumbersome equipment and crews.

In the end, this essay film is about much more than the drawings and paintings. Just as Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbooks show his passions, his changes of mind, his trains of thought and visual thinking, so this film is an almost mythic encounter with the imagination of this great artist, who extended cinema, was profoundly political, engaged with questions about power, existentialism, memory, destiny, psychology, space and light. These ingredients make The Eyes of Orson Welles not only a portrait of a great man, but an account of the 20th century and a meditation on the continuing relevance of his genius in what Mark describes as these Wellesian times.

Last on

![]()

Simon Callow on Orson Welles

Listen as Matthew Parris meets actor Simon Callow to discuss the life of Orson Welles.

![]()

Seven things you might be surprised to learn about Citizen Kane

We reveal the secrets of a movie hailed by many critics as the greatest of all time.

![]()

Orson Welles

Listen to Orson Welles in this in-depth and revealing interview from 1955.

Music Played

-

![]()

Anton Karas

Holly Runs After Harrys Shadow

-

![]()

Henry Mancini

Tana's Theme

-

![]()

Anita Ellis

The Lady From Shanghai: Please Don't Kiss Me

-

![]()

Anton Karas

Holly and Harry Meet At The Praters Big Wheel

Credits

| Role | Contributor |

|---|---|

| Narrator | Mark Cousins |

| Orson Welles | Jack Klaff |

| Participant | Beatrice Welles |

| Editor | Timo Langer |

| Writer | Mark Cousins |

| Executive Producer | Michael Moore |

| Executive Producer | Mark Thomas |

| Producer | Mary Bell |

| Producer | Adam Dawtrey |

| Director | Mark Cousins |

Broadcasts

- Sun 13 Jan 2019 21:00

- Thu 6 May 2021 22:00

- Fri 12 Jan 2024 00:00