Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent

Neil MacGregor's world history explores the great empires of the world around 1500 - the threshold of the modern era. Today he examines the signature of Suleyman the Magnificent.

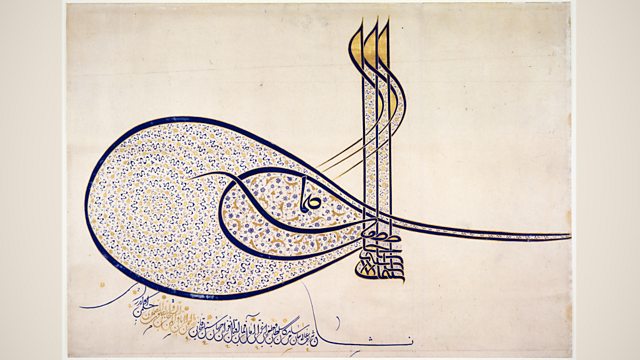

Neil MacGregor's world history as told through things. This week he is exploring the great empires of the world around 1500 - from the Inca in South America to the Ming in China and the Timurids in the Middle East. Today he is with the great Islamic Ottoman Empire that, by 1500, had conquered Constantinople as its new capital. The object Neil has chosen to represent this empire is the personal signature of the great Ottoman ruler Suleyman the magnificent, a contemporary of Henry V111 and Charles V. This monogram is the ultimate expression of Suleyman's authority at this time - a stamp of state and delicate artwork rolled into one. The Turkish novelist Elif Shafak and the historian Caroline Finkel help explore the power and meaning of this object.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

More episodes

Previous

You are at the first episode

![]()

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

About this object

Location: Turkey

Culture: Islam

Period: AD 1520 - 1566

Material: Paper

��

This document is a tughra, the official signature of the ruler of the Ottoman Empire - Suleiman the Magnifcent. This example would have been placed at the beginning of a state document to guarantee its authenticity. The origin of the tughra's looping shape is unknown but it may have been inspired by the silhouette of a falcon or a piece of horse hair. Sultans would choose their own personal tughra from a range of signatures drawn up by a court calligrapher on the day of their accession.

Who were the Ottomans?

Under the rule of Suleiman the Magnifcent (1520 - 1566) the Ottoman Empire reached its height. The inscription on this Tughra - 'the one who is always victorious' - is a fitting tribute to Suleiman's military prowess. Suleiman personally led his armies into battle and he captured Belgrade, Rhodes and large areas of Iran. He was also a keen patron of the arts and calligraphy flourished during his reign. The empire was never as strong after Suleiman's death but the Ottomans continued to dominate the Middle East and the Mediterranean until the 1800s.

Did you know?

- Suleiman is also known in Turkey as 'the Lawmaker' because of his complete reconstruction of the Turkish legal system.

The golden age of the Ottomans

By Elif Shafak, Turkish author

��

At school we read about Suleiman the Magnificent, you know, his life. Nevertheless in history books I don’t think we get to understand the feelings of the human being, you need to read other things to understand that world better.

One of the interesting things about Suleiman the Magnificent’s life was his great love for Hürrem Roxelana and that’s something we still widely talk about in Turkey, this big, amazing, unforgettable love story. In the Western world when people talk about Ottomans, sultans they almost instantly think about harems, many women come to mind, but when you look at Suleiman the Magnificent’s life it wasn’t like that at all. He was very much in love with one woman and to him she was so precious. There are these poems he wrote for her, he dedicated so many things to her and she had an amazing power in the palace.

There’s an amazing respect for particularly Suleiman’s age. It was called the Golden Age of the Ottomans. They made amazing achievements and I’m not talking about solely military achievements, culturally it was a very prolific time. There was a lot of interest in arts, in poetry, in calligraphy at the time, artists were very much supported. The Sultan himself was writing poems - poets were very well received in the palace. It was also a cultural renaissance for the Ottomans, so in many ways I think people have a lot of respect for Suleiman the Magnificent’s era and his approach.

I think the Ottoman Istanbul is a place that I love to visualise. It is such a colourful place. Sometimes we complain today about how Istanbul is so crowded, but in an interesting way it was always a very crowded place. It always had its rhythm and fast energy.

In terms of architecture, how well do we preserve Ottoman buildings? We’re not very good at that in Turkey, we need to improve. Sometimes you would see a bunch of very ancient old Ottoman tombs or tombstones just squeezed between two apartment buildings so when people washed their clothes and put their laundry on the balcony they look at these tomb stones. We live together – the dead and the living, the ghosts and the people who are alive today. I like to think of Istanbul as a city in which the dead and the living live together.

What is a tughra?

By Caroline Finkel, Ottoman historian and author

��

You could think of it as an imperial cipher or monograph perhaps, because it contains within it the names of each Sultan, who had his own tughra designed when he came to power, so it has the name of the Sultan, his father, and then a formula saying ‘ever victorious’. So if we look at the British Museum tughra, you can read within it the word ‘Suleiman Shah, bin (meaning ‘son of’) Selim Han Shah (Selim being his father) and ‘El Muzzafah daim’. The little bit at the left inside the big loop, daim, means ‘ever’. So ever victorious, El Muzzafah daim’.

It developed – it was rather simple at first – over time. It developed in these different, various Turkish cultures, and with different Sultans according to, perhaps, the ambitions of the Empire at that time: the ambitions of the calligrapher, perhaps, of the decorator. It was put together both by a calligrapher and a decorator who did all the fancy work, the little flowers etc. The beautiful artistry you see in the British Museum example. Suleiman’s perhaps impresses more than any of the others though later and earlier Sultans had almost, sort of, flights of fancy tughras, containing the same formula of course.They were used on the top of official documents, orders, Sultanic orders, but they were also used on property deeds, you know, for instance they could be just in black and white, the same design, simpler. They were used on the deeds of charitable foundations which were very important to the Ottomans and other Islamic cultures. They were used on official buildings, and on coins, for instance.

So they were very widely used and most people of course at that time were not able to read them, but they could recognise them. You could have an image of this thing and they knew what it meant.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Mon 13 Sep 2010 09:4591�ȱ� Radio 4 FM

- Mon 13 Sep 2010 19:4591�ȱ� Radio 4

- Tue 14 Sep 2010 00:3091�ȱ� Radio 4

- Mon 9 Aug 2021 13:4591�ȱ� Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Leaders and Government—A History of the World in 100 Objects

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

![]()

Shakespeare - African Treasure

Shakespeare - African Treasure

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects