Episode Transcript – Episode 71 - Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent

Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent (made between 1520 and 1566), from Turkey

Welcome to part three of this history of the world through objects, which we pick up between 1400 and 1500. As always, we're looking at 'things', that tell us about how societies organised themselves, how they viewed their place in the world, and how they traded with - and almost invariably fought with - their neighbours.

At regular intervals we've been spinning the globe to see what has been happening on different continents at the same time, and we've seen that for thousands of years objects have travelled huge distances over land and sea. But in spite of these connections, the world before1500 was essentially still a series of networks. Nobody could take a global view because nobody had ever travelled round the world. Before 1500 nobody could spin the globe. The programmes this week are about the great empires of the world at that last, pre-modern, moment, when it was still unthinkable for one person to visit them all, and when even superpowers dominate only their regions.

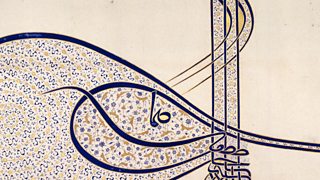

We begin with one of the great rulers of the age, or more specifically with his name - painted across two feet (60 cm) of paper, refulgent in blue and gold, and proclaiming him ruler of a dynamic and expansive Islamic empire. An empire that would reconfigure the geopolitics of the entire world.

"It speaks of power, glory, magnificence, and there's a statement behind his signature." (Elif Shafak)

"It gave you a sense of the imperial, of being part of a whole, of this great and, at that time, very successful enterprise that was the Ottoman Empire." (Caroline Finkel)

Between about 1350 and 1550, great tracts of the world were occupied by superpowers - from the Inca in South America to the Ming in China, the Timurids in central Asia and, in between them, the vigorous Ottoman Empire, which spanned three continents and ran from Algiers to the Caspian, from Budapest to Mecca. Two of the empires I'm talking about this week lasted for centuries; the other two collapsed within a couple of generations. Why? The answer, I think, is that the ones that lasted endured not only by the sword, but also by the pen - that is, that they had flourishing and successful bureaucracies that could sustain them through tough times and incompetent leaders.

And the enduring power that we're looking at in this programme is the Islamic Ottoman Empire that, by 1500, had conquered Constantinople and was moving from being a military power to an administrative one. In the modern world, as the Ottomans demonstrated, paper is power. So it is a piece of paper that is this programme's object.

But what a piece of paper it is! It's about two feet (60 cm) wide, one and a half feet (45 cm) high, and it's a very beautiful painted drawing. It's a monogram, it's a badge of state, it's a seal of authority and it's a work of the highest art. It's called a tughra.

This tughra has been drawn on heavy paper in bold lines of cobalt blue - brilliant blue lines. Three strong verticals and a great sweeping loop to the left, and a tail that runs off to the right, and inside those lines, what looks like a tiny meadow of colourful golden-blue flowers. It's been cut from the top of an official document, and the whole design spells out the name and the title of the sultan whose authority it represents. The words combined in this elaborate pattern read: "Suleiman, son of Selim Khan, ever victorious". This simple Arabic phrase, elaborated into an emblem made out of lavish and opulent materials, speaks clearly of great wealth, and it's no surprise that this ever-victorious sultan, the contemporary of Henry VIII in England and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, was called by Europeans Suleiman the Magnificent.

In 1520, Suleiman inherited an empire that was already expanding, and that he went on to consolidate and extend with almost unstoppable energy. Within just a few years, his armies had shattered the kingdom of Hungary, taken the Greek island of Rhodes, secured Tunis, and fought the Portuguese for control of the Red Sea. Italy was now in the front-line. Suleiman seemed to envisage a restoration of the Roman Empire, but under Muslim rule, and I find it intriguing that this dream of recovering an Ancient Roman glory, which fired the Renaissance in western Europe, was also a spur to the great Ottoman achievement. The two hostile worlds - Christian and Islamic - shared the same impossible dream.

When a Venetian ambassador expressed the hope of one day welcoming the Sultan as a visitor to his city, Suleiman replied: "Certainly, but after I have captured Rome". He never did capture Rome, but today he is without doubt considered the greatest of all the Ottoman emperors. Here's the Turkish novelist, Elif Shafak.

"Suleiman was an unforgettable sultan for many people, for the Turks definitely. In the west he was known as "Suleiman the Magnificent", but we know him as "Suleiman Kanuni Suleiman", who is the "law-maker", because he changed the legal system. I must say, Suleiman was very interested in conquering east and west, and that's why many historians think that he was inspired also by Alexander the Great. So I see that statement, that world power, in this calligraphy as well."

How do you govern an empire the size of Suleiman's, and ensure that power in the centre is properly deployed at the edge? You need a bureaucracy, and administrators all over the empire need to be able to demonstrate that they have the authority of the ruler. This is done by issuing a visible emblem that can be carried and shown to everyone, and that emblem is the tughra. It acted like a warrant, or a sheriff's badge, giving officers of the Empire the stamp of power. The tughra would be at the top of all important official documents, and Suleiman issued about 150,000 such documents in his reign. He was industrious in establishing diplomatic ties, in creating a formidable civil service and promulgating new laws. All of this required letters of state, instructions to ambassadors, legal documents, and so on.

And documents like that would have had a tughra like this. The tughra itself names the Sultan, while the line below reads: "This is the noble and exalted sign of the Sultan's name, the revered monogram that gives light to the world. May this instruction, with the help of the Lord and the protection of the Eternal, be given force and effect. The Sultan orders that ..."

At this point, our paper has been cut, but the document below would have continued with whatever instruction, law, or command was meant to follow. Interestingly, there are two languages in our bit of paper. The tughra itself names the Sultan in Arabic, reminding us that Suleiman is the caliph, the protector of the faithful, with a duty to the whole Islamic world. The words below it are written in Turkish, and proclaim Suleiman's role as Sultan, ruler specifically of the Ottoman Empire, and sovereign of all its subjects - Muslim, Jewish or Christian. So we have Arabic for the spiritual world, Turkish for the temporal.

So who would have read this inscription? Well, given the opulent artistry of this tughra, the recipient must have been very grand, so it might have been a governor or a general, a diplomat or perhaps a member of the ruling house. And it could have been sent to any part of Suleiman's fast growing empire, as historian Caroline Finkel explains:

"He overthrew the Mamluk Empire, so Egypt and Syria with all their Arab population. The Hejas of course as well, with the holy places which were extremely important. All these people were now Ottoman subjects, for better or worse. Suleiman's tughra could be seen as far as the Persian border, where their great rival in the east, the Shia Safavid Empire, was always trying to challenge the Ottomans; in North Africa, where Ottoman naval expeditions were having great success against the Spanish Hapsburgs in the western Mediterranean; and up into the lower reaches of what we now call Russia - Muscovy then."

So, Suleiman's Ottoman Empire controlled the whole coastline of the eastern Mediterranean, from Tunis all the way round almost to Trieste. It was this huge new state that compelled the western Europeans to look for other ways of travelling to, and trading with, the east, this new state that forced them from the Mediterranean out into the Atlantic.

Most official documents get lost. They're destroyed or they're thrown away. Our driving licences, our tax bills, don't usually survive our deaths. So the huge bulk of the official paper of the Ottoman Empire is lost to us. The most likely reason for keeping any official document is if it's to do with land, because subsequent generations need to know the authority by which the land is owned. So if I had to guess what our tughra was for, I would take a bet on it being a document giving a major grant of land, conferring or confirming a huge estate. That would explain why the document survived long enough for a later collector, probably in the nineteenth century, to cut the tughra out of it and sell it as a separate work of art. Because it is a work of art.

In between the strong lines of cobalt blue edged with gold leaf are great loops, containing riotous flowerbeds of spiralling lotus and pomegranate, tulips, roses and hyacinths. This is magnificent Islamic decoration, rejoicing in natural forms while avoiding the human body, and it's also a virtuoso demonstration of calligraphy - of sheer skill and joy in writing. The Ottoman Turks, like their predecessors and contemporaries across the Islamic world, held the art of writing in high esteem. The word of God had to be written with all the beauty of holiness.

Calligraphers were also important bureaucrats, who staffed the Turkish chancery, and they developed a beautiful and extremely intricate script - it's notoriously difficult to read, and deliberately so. Because this is a script designed to prevent extra words being inserted into the text, to prevent the forgery of official documents. So the calligraphers that made our tughra were security managers as well as bureaucrats and, above all, artists, often belonging to dynasties of craft skill passed from one generation to the next. In the Islamic world red tape can often be high art.

Modern politicians often proudly announce their desire to sweep away red tape. The contemporary prejudice is that too much paper-work slows you down, clogs things up. But if you take a historical view, it's bureaucracy that sees you through the rocky patches, and enables the state to survive. Bureaucracy is not evidence of inertia, it is life-saving continuity, and it enabled the Ottoman Empire to continue from the time of Suleiman till the First World War.

Tomorrow, I'm with another piece of paper - from the longest surviving state in the world, and it's no coincidence that it also has the longest tradition of bureaucracy. I'll be in China, with a piece of paper that's like the tughra. It was a powerful tool of the enduring state ... paper money.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.