Episode Transcript – Episode 99 - Credit card

Credit card (issued 2009), from United Arab Emirates

If you asked anyone which twentieth century invention had most impact on our daily lives today, instant answers might include the mobile phone or the personal computer. I suspect not many people would think first of the little plastic rectangles that fill our wallets and purses. Yet since they emerged in the late 1950s, credit cards have become, in every sense, part of the currency of life. Bank credit is now, for the first time in history, no longer the prerogative of the elite and, maybe as a result, the long dormant religious and ethical debate about the use and abuse of money has been reborn in the face of this ultimate symbol of triumphant consumer culture. Today's object, our penultimate in this History of the World through things, is indeed a credit card. But it's a slightly unusual one, and it leads us to a perhaps unexpected conclusion about the way our world now behaves and believes.

"If everyone were able to make every transaction through a credit card, then would you actually need money in the conventional sense at all?" (Mervyn King)

So far this week, I've chosen objects with which to explore some of the key elements of twentieth-century life and living - sex and human rights, revolution, war and the aftermath of war. It's now the turn of that third great constant of human affairs, money. I couldn't finish this History of the World without going back to it.

It's featured throughout the series, from gold coins of the proverbially rich King Croesus, to the paper currency of Ming China and the first currency to go global - the King of Spain's pieces of eight. Today's global currency is neither metal nor paper, indeed it's not really money at all, it is a promise in plastic.

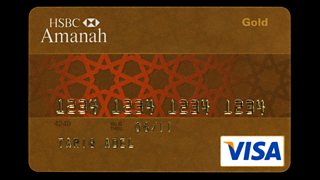

We all know the dimensions of this particular piece of plastic, because every credit card in the world is of the same internationally-agreed size and shape, so that they can all fit into the "holes in the wall" that now puncture our urban universe. It's got on it the name of the bank, and the usual run of numbers that identify it, and us as its user. This one happens to be coloured gold, and it's got a confirming inscription which says, in text on the top right-hand side of the card, "Gold". It wants us to know that it's a portal to big spending-power. This virtually weightless bit of plastic is worth a good deal of gold.

Of course, a credit card as such isn't itself money, it's merely a physical object that provides a way of promising money, moving it and spending it. None of us is now ever likely to see the money we've saved - it appears simply as long strings of numbers on statements and receipts. Money has lost its essential materiality and, with the flick of a few fingers, it can be conjured up virtually anywhere in the world, instantly.

All the coins or the banknotes we've looked at so far in this series have had king or country stamped on them, but our card acknowledges no ruler or nation, and no limit to its reach, other than its own plastic mortality, its expiry date. This new way of handling money gives us cash without frontiers, and it has conquered the world. Yet, even on credit cards, the aura of traditional money remains. The card that's telling our story proudly bills itself as a gold card. Croesus is still with us. This card is telling us that, like all the best money, it is as good as gold. And so even a complete stranger can be confident that he will ultimately be paid.

For Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England, these cards are merely a new solution to the age-old problem of how far you can trust a stranger. Here he is:

"As in all types of money or cards used to finance transactions, the acceptability, the trust, which the other side of the transaction puts in it, is paramount. If I could give a different example, which I think illustrates the importance of trust here . . . when Argentina had its financial collapse, and it reneged on its national debt in the 1990s, the currency became worthless, and in some of the villages in Argentina, the use of IOUs as a substitute for paper currency started to grow up. The problem with an IOU is that the 'U' has to trust the 'I' - and that may not always be the case. So what happened was that, in the villages, some of them would take the IOU to the local priest, and ask him to endorse it. Now that was an example, in terms of the use of religion, which was not fundamentally about religion as such, but was about enhancing the trust that people had in the instrument that was being used."

In the absence of a village priest with global reach to endorse our IOUs, we use credit cards which span the world. This particular gold card carries two brand names familiar all round the world. One tells us that it is issued by a London-based bank, a name familiar on every British high street. The other tells us that it functions through the backing of a US-based credit association. But the card also has on it writing in Arabic. In short, this card is connected to the whole world, part of a global financial system, backed up by a complex electronic superstructure that most of us hardly think about as we key in our PIN numbers. All our credit card transactions, carried out with cards like this one, are tracked and recorded, building a huge dossier of our movements and purchases, and slowly writing our economic biographies as we move around the world.

It's an extraordinary development. We are free now, as never before, to spend our way round the globe, but most of us haven't the slightest idea how this system of moving money actually works. Even more important, we don't know who is monitoring our spending, or what they do with the information they gather. As they know more and more about us, we know less and less about them. The one thing we do know is that the banks - that this recent technology makes possible - are far beyond anything previously known, and that their global power transcends national boundaries. Here's Mervyn King again:

"The spread of a wide range of financial transactions, whether using cards issued by international banks or using the other services that they offer, have created institutions which are trans-national, which are bigger than the ability of national regulators to control, and which, if they do get into financial difficulties - fortunately not many have, but where they do get into difficulties - then, as we've seen, they can cause enormous financial mayhem."

In one respect, cards are like traditional coins and banknotes. They've got two sides, each holding important information. But the difference is that the back of the credit card holds information we can't read. That black magnetic strip is the electronic verification system that allows us to move money around the world relatively securely, and that permits instant communication, instant transactions and instant gratification. It's this micro-technology, one of the great global achievements of the last generation, that has made the worldwide credit card possible, and with it, worldwide banks. This little black strip is the hero, or the villain, of this programme. All the rest is simply a consequence of it.

Credit cards do something that was never possible before. They allow ordinary people to borrow at relatively low cost, avoiding both the pawnbroker and the loan-shark. Of course, such opportunities bring risk, and easy credit undermines traditional values like thrift - you don't have to save before you can spend. So it's not surprising that this new instrument of credit quickly became a target of concern for moralists and religious leaders, branded as dangerous, even sinful, in its very nature - and that it led to a new, loaded vocabulary. The "shopaholic" is our equivalent of the old-fashioned "spendthrift" and "wastrel". "Flashing the plastic" would certainly figure in any modern 'Rake's Progress'. Type in "credit card debt" on a search engine on the web, and you will find harrowing tales of lives wrecked by profligacy. It's merely the latest manifestation of the perennial dangers of living beyond our means, and of the perils of money-lending - always an urgent issue for the world's religions. Which leads us back to our card.

In the middle of it is a decorative rectangular strip, with criss-crossing red stars. It's curiously reminiscent of an object we discussed in one of last week's programmes - the drum from Sudan. This is Islamic patterning, and we know that it was carved on the side of the drum when it was taken to the Islamic north of Sudan, and branded to show the new world to which it now belonged. The decoration on our card makes the same point. It shows it was not just issued by a London bank, but by that bank's Islamic finance wing, based in the Gulf. The decoration announces that this card is different from ordinary credit cards - it's compliant with Sharia law.

All the Abrahamic religions have worried about the social evils of usury - the charging of interest. Both the Bible and the Qur'an have forthright things to say about it, from the prohibitions of Leviticus - "Thou shalt not give him money upon usury, nor lend him thy victuals for increase" (Leviticus 25:37) - to the scathing words of the Qur'an - "Those that live on usury shall rise up before God like men whom Satan has demented by his touch." (Qur'an, 2: 275)

The most recent manifestation of this age-old concern has been the rise of Sharia-compliant Islamic banking, offering services consistent with Islamic religious belief. Islamic banks are not permitted to invest in alcohol, the arms trade, pornography or gambling, and our Islamic credit card is paid for by a fixed service charge, not by interest. Here's Razi Fakih, from the Islamic wing of HSBC, known as Amanah, and based in Dubai:

"Islamic finance is a very new industry, the industry related to conventional industry. Conventional banking and finance has been around for as long as we all remember. Islamic finance started some time in 1960s Egypt, and I think it is only in the 1990s that it actually took off. If you were to go back to the early beginnings of Islamic finance, that's about just four decades old, but if you are to look at the recent development, and where it has really taken on a significant usage, it's only since 1990. So it's just less than two decades old, in that context."

This recent development, tying religion to the heart of commercial activity, runs counter to what, for most of the twentieth century, had become the received wisdom. Most intellectuals and economists from the French Revolution onwards, including Marx himself, assumed that religion would steadily dwindle as a force in public life. One of the striking facts of the first decade of the twenty-first century has been the return of religion to the centre of the political and economic stage in large parts of the world. Our gold Islamic credit card is part of that growing global phenomenon, one of many attempts to find a new accommodation between those old opponents, God and mammon.

The next programme is our last. The hundredth object has been the hardest to choose. It looks both to the future and to the past, and it could help change lives all around the globe. I hope everyone will agree that it deserves its place in this History of the World through things.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.