Episode Transcript – Episode 47 - Sutton Hoo Helmet

Sutton Hoo helmet (made seventh century AD) found in Suffolk, England

Yesterday we were in the heat of Arabia, tracking the rise of the Islamic Empire and the reshaping of Middle Eastern politics after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. Today, we're still in the seventh century, but I'm shivering in the chill of East Anglia, at a place where, in the summer of 1939, poetry and archaeology unexpectedly intersected and transformed our understanding of British national identity.

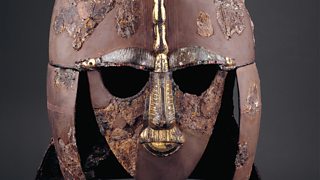

All the hundred objects in this series are, I hope, evocative of distant worlds, but some, like today's object, possess an almost magical power to carry us into the past. It's a helmet. Its discovery was part of one of the great archaeological finds of modern times, and it speaks to us across the centuries with a haunting intensity.

"An embossed ridge, a band lapped with wire, arched over the helmet, head protection to keep the keen ground cutting edge from damaging it when danger threatened, and a man was battling behind his shield." (Seamus Heaney)

I'm in East Anglia, a few miles from the Suffolk coast, and the wind is howling straight from the Urals. I'm at Sutton Hoo, where in 1939 one of the most important and most exciting archaeological discoveries in Britain was made. It uncovered the tomb of an Anglo-Saxon who had been buried here in the early 600s, and it completely changed the way we thought about what had been called the "Dark Ages" - those centuries that followed the collapse of Roman rule in Britain. I'm with Angus Wainwright, the National Trust archaeologist for the East of England... what can we see of the site now?:

"Well we're standing amongst a number of large mounds, high up on an exposed ridge looking down towards the River Deben. We're about 100 feet (30 m) up here, and we're standing next to one of the biggest mounds, which we call, excitingly, Mound 1, which is where the great ship grave was discovered in 1939. And we've got about 18 or 20 other mounds around us."

It was in this ship grave that the famous Sutton Hoo helmet was found. Surprisingly, there was no body, but in the ship's burial chamber there was an astonishing range of valuable goods drawn from all over Europe: weapons and armour, elaborate gold jewellery, silver vessels for feasting, and many, many coins. Nothing like this from Anglo-Saxon England had ever been found before.

The discovery of this ship burial in the summer of 1939 captured the British public's imagination. It was hailed as the "British Tutankhamun". But the politics of 1939 lent a disturbing dimension to the discovery: not only did the excavation have to be hurried because of the approaching war, but the burial itself spoke of an earlier, and successful, invasion of England by a Germanic-speaking people. Here's Angus Wainwright again... what did they actually discover when they excavated in 1939?:

"The first thing they discovered very early on in the excavation were ship rivets - these are the iron rivets that hold together the planks of a ship. They also discovered that the wood that had made up the ship had rotted completely away, but by a rather mysterious process, the shape of the wood was preserved in a kind of crusted blackened sand, so by careful excavation they gradually uncovered the whole ship. And the ship is 27 metres long, so it's longer than the biggest of the ocean-going yachts. It's a really massive ship, it's the biggest, most complete Anglo-Saxon ship ever found."

We're inland. Why would anybody here want to be buried in a ship?

"Ships were very important to these people. The rivers and the sea were their means of communication. It was much easier to go by water than it was by land at this time, so that people, say, in modern Swindon, would have been on the edge of the world to these people. Whereas people in Denmark and Holland would be close neighbours."

And the big question of course - for anybody looking at the grave and what was found in the grave - is that there's no body. Where do you think the body is?

"Well, the absence of the body was a bit of a mystery when the excavation happened, and people wondered whether this could be a cenotaph - i.e. a burial where the body had been lost - so it's a sort of symbolic burial if you like. But nowadays we think a body was buried in the grave, but because of these special acidic conditions of this soil it just dissolved away. What you have to remember is that a ship is a water-tight vessel, and when you put it in the ground the water percolating through the soil builds up in it and it basically forms an acid bath in which all these organic things like the body and the leatherwork and the wood dissolve away, leaving nothing."

We still don't know who that owner was, but the Sutton Hoo helmet put a face on an elusive past, a face that has ever since gazed sternly out from books, magazines and newspapers. It's become one of the iconic objects of Britain's history.

It's the helmet of a hero, and when it was found, people were immediately reminded of the great Anglo-Saxon epic poem 'Beowulf'. Until 1939, it had been taken for granted that Beowulf was essentially fantasy, set in an imaginary world of warrior splendour and great feasts. The Sutton Hoo grave ship, with its cauldrons, drinking horns and musical instruments, its highly wrought weapons and lavish skins and furs, and not least its hoard of gold and silver, was evidence that 'Beowulf', far from being just poetic invention, was a surprisingly accurate memory of a splendid, lost, pre-literate world.

Think for a moment of the helmet, decorated with animal motifs made out of gilded bronze and silver wire and bearing the marks of battle; now listen to the poet Seamus Heaney reading from 'Beowulf':

"To guard his head he had a glittering helmet

that was due to be muddied on the mere-bottom

and blurred in the upswirl. It was of beaten gold,

princely headgear hooped and hasped

by a weapon-smith who had worked wonders

in days gone by and adorned it with boar shapes;

since then it had resisted every sword."

('Beowulf', lines 1448 - 54)

Clearly the Anglo-Saxon poet must have looked closely at something very like the Sutton Hoo helmet. Seamus Heaney was reading from his own translation of 'Beowulf' - what does the Sutton Hoo helmet mean to him now?:

"I never thought of the helmet in relation to any historical character. In my own imagination it arrives out of the world of Beowulf, and gleams at the centre of the poem and disappears back into the mound. The way to imagine it best is when it goes into the ground with the historical king, or whoever it was buried with, then its gleam under the earth gradually disappearing.

"There's a marvellous section in the Beowulf poem itself - the Last Veteran it's called - the last person of his tribe, burying treasure in the hoard and saying: 'Lie there treasure, you belong to earls, the world has changed'. And he takes farewell of the treasure, and buries it in the ground. That sense of elegy - a farewell to beauty and farewell to the treasured objects - that hangs round the helmet, I think.

"So it belongs in the poem, but obviously it belonged within the burial chamber in Sutton Hoo. But it has entered imagination, it has left the tomb and entered the entrancement of the readers, I think, of the poem - and of the viewers of the object in the British Museum."

The Sutton Hoo helmet belonged of course not to an imagined poetic hero, but to an actual historical ruler. The problem is we don't know which one. It's generally supposed that the man buried with such style must have been a great warrior chieftain, and because all of us want to link finds in the ground with names in the texts, for a long time the favoured candidate was Raedwald, king of the East Angles, mentioned by the Venerable Bede in his History of the Anglo-Saxons and probably the most powerful king in all England around 620.

But we can't be sure, and it's quite possible that we may be looking at one of Raedwald's successors or, indeed, at a leader who's left no record at all. So the helmet still floats intriguingly in an uncertain realm on the margins of history and imagination. Here's Seamus Heaney again:

"Especially after 11 September 2001, when the firemen were so involved in New York, the helmet attained new significance for me personally, because I had been given a fireman's helmet way back in the 1980s by a Boston fireman which was heavy, which was classically made, made of leather with copper and metal spine on it and so on. I was given this, and I had a great sense of receiving a ritual gift, not unlike the way Beowulf receives the gift from Hrothgar after he kills Grendel."

In a sense, the whole Sutton Hoo burial ship is a great ritual gift, a spectacular assertion of wealth and power on behalf of two people - the man who was buried there and commanded huge respect, and the man who organised this lavish farewell and commanded huge resources. We are clearly in the presence of power.

The Sutton Hoo grave ship brought the poetry of Beowulf unexpectedly close to historical fact. In the process it profoundly changed our understanding of this whole chapter of British history. Long dismissed as the Dark Ages, this period - the centuries after the Romans withdrew - could now be seen as a time of high sophistication and extensive international contacts, that linked East Anglia not just to Scandinavia and the Atlantic, but ultimately to the eastern Mediterranean and beyond.

The very idea of ship burial is Scandinavian, and the Sutton Hoo ship was of a kind that easily crossed the North Sea, so making East Anglia an integral part of a world that included modern Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The helmet is, as you might expect, of Scandinavian design. But the ship also contained gold coins from France, Celtic hanging bowls from the west of Britain, Imperial table silver from Byzantium, and garnets which may have come from India or Sri Lanka. And while ship burial is essentially pagan, two silver spoons clearly show contact - direct or indirect - with the Christian world.

These discoveries force us to think differently, not just about the Anglo-Saxons, but about Britain. For whatever may be the case for the Atlantic side of the country, on this side of the island, the East Anglian side, we have always been part of the wider European story, with contacts, trade and migrations going back thousands of years.

As I leave Sutton Hoo I'm struck by a paradox. I travelled here through Constable country - the landscape that's become for us all synonymous with Englishness. The Anglo-Saxon ship burial here takes us at once to the world of Beowulf, the foundation stone of English poetry. You can't help feeling that here you are near the heart of English national identity. Yet not a single one of the characters in Beowulf is actually English. They're Swedes and Danes, warriors from the whole of northern Europe, while the ship burial here contains treasures from the eastern Mediterranean and from India. The history of England that you can tell from these objects is a history of the sea as much as of the land. Of an England long connected to Europe and to Asia which, even in 600 AD, was being shaped and re-shaped by the world beyond itself.

-

![]()

Listen to the programme and find out more.