Book at Bedtime: A short guide to abridging, in 10 parts

27 July 2015

Ever since The Three Hostages by John Buchan was , Book at Bedtime has been giving audiences the pleasure of being read to as sleep beckons. The latest book to be abridged, by radio dramatist ROBIN BROOKS, is Harper Lee's Go Set a Watchman. Brooks' job is to cut the works of great novelists down to size for the listener. He has previously grappled with , and . Here he gives the inside track on the art of abridging.

begins on Radio 4's Book at Bedtime on 10 August.

My dear producer Eilidh McCreadie asked me to write about abridging for Book at Bedtime, and I duly turned out a detailed account. But she said, gosh, Robin, this is a bit long, why not cut it down into ten short episodes?

1.

First of all, the maths. Your 14-minute episode allows you approximately 2,000 words. So – if you’re lucky enough to get 10 episodes – that’s 20,000 words total.

2.

But the novel you’ve been given may be getting on for – like, e.g., To Kill a Mockingbird – 100,000 words... or more. So now you’ve got to get rid of at least 80% of the original.

3.

How can you possibly do justice to some great masterpiece while chucking away most of it?

4.

You can’t. But the slot remains popular – no plans to abolish Book at Bedtime I’ve heard of yet – it must work somehow. So what can you do?

5.

You know it’s at least a flavour of the original. You might take comfort from the fact that the listener will at least hear the writer’s voice; this is no small thing, this is sort of .

6.

Some kinds of fiction are easier to abridge than others. “” is a welcome word. Anything episodic is good. Choose some. Cut others. Bingo!

Don Quixote: A picaresque novel

7.

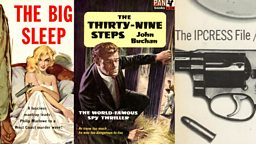

Don’t go near a detective plot. You have to leave out most of the red herrings, and then what’s the point?

The Big Sleep: Hardboiled & labyrinthine

8.

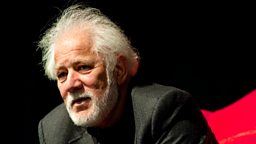

Also avoid authors who create a tightly-woven tapestry in which one pulled thread unravels all. That cunning swine , for instance. Treat him and his like with caution.

'Bogies' & Greene - a tough day for the abridger

9.

Anyway, you can enjoy chopping things to pieces! Because –

10.

Actually, it is an education, and even a bit of a privilege, to be hired to get your knife into a fine novel, and hack and slash and work out which bit is the beating heart, and which just the… appendix.

Related

-

![]()

Readings from modern classics, new works by leading writers and literature from around the world

-

![]()

Clips and production notes from Robin Brooks' adaptation of Joyce's novel, broadcast on Bloomsday 2012

-

![]()

Writer Andrew Smith visited Monroeville, Alabama in 2011 to see how life had changed in the previous half-century

-

![]()

War reporter and author Tim Butcher chooses Graham Greene for Radio 4's Great Lives

-

![]()

Book readings from Radio 4 available on 91热爆 iPlayer

More from Books

-

![]()

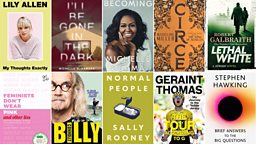

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

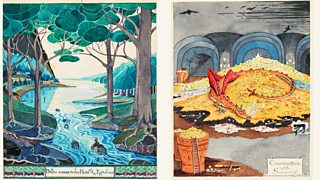

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

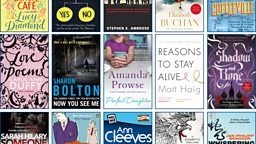

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.