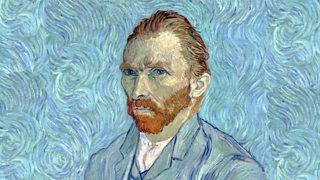

London calling: How the capital inspired Vincent van Gogh

25 March 2019

Before he started his career as an artist, Vincent van Gogh spent time living and working in Britain. WILLIAM COOK explores how London, its suburbs, and an English seaside town influenced one of history’s greatest painters.

Vincent Van Gogh is commonly associated with three countries: Holland, where he was born and raised; Belgium, where he became an artist; and France, where he produced his greatest paintings and died by his own hand, aged just 37. However there is one country that’s often overlooked. Between 1873 and 1876, in his early twenties, Van Gogh lived in Britain, and now this obscure sojourn is the focus of an illuminating new exhibition.

He came to London as a youth. He left as a young man

The Van Gogh and Britain exhibition isn’t confined to Van Gogh’s time in Britain. It examines the British artists who influenced him, and the British artists he inspired.

However the most fascinating part of this forgotten story is the three years he spent in London. He didn’t become an artist here, but London was a lasting inspiration. He came here as a youth. He left as a young man.

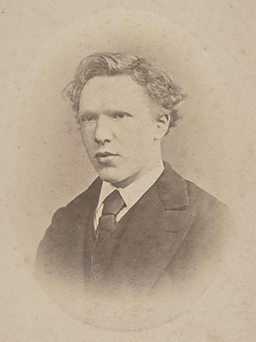

Vincent came to London in March 1873. He’d just turned 20. Through his uncle, an art dealer, he’d landed a job with the art dealers Goupil & Co, in Brussels. After a few months Goupil raised his salary and transferred him to their London offices, at 17 Southampton Street in Covent Garden (still a fruit and vegetable market back then). Vincent was glad to go. London was the biggest city on earth and, in many ways, the most modern. For a young man who wanted to see the world it was a dream come true.

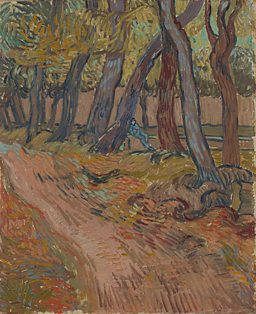

Vincent’s job at Goupil was mundane, but he didn’t mind the work – at first. In his free time he roamed around London, exploring its parks and gardens. He went rowing on the Thames and saw the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy.

He also visited Dulwich Picture Gallery and the National Gallery, where he admired the portraits of Reynolds and Gainsborough, and the English landscapes of Constable and Turner. He especially liked Constable: “He is splendid!” wrote Vincent, in a letter to his brother Theo. He read the poetry of Keats, which appealed to his romantic nature, and the novels of Dickens, which fired his keen sense of social justice.

Vincent found lodgings at 87 Hackford Road in Stockwell, near the Oval cricket ground. Then as now, Stockwell was a mixed neighbourhood, with white collar and blue collar workers living side by side. “Things are going well for me here,” he wrote to Theo. “I have a wonderful home, and it’s a great pleasure for me to observe London and the English way of life.”

Vincent’s landlady, Ursula Loyer, was the widow of a French pastor. She ran a small school on the ground floor of this terraced house – perhaps this was the inspiration for Vincent’s subsequent attempts to become a schoolmaster. Ursula lived upstairs, with her 19 year-old daughter, Eugenie, and Vincent fell hopelessly in love with her. He eventually asked her to marry him, but she said no (she told him she was secretly betrothed to someone else). Heartbroken, Vincent returned home to his family in the Netherlands.

Vincent returned to London a year later, in the autumn of 1874. This time, he was accompanied by his sister Anna, who hoped to find work in Britain as a governess (it seems she was unsuccessful). They lodged at 395 Kennington New Road, between the Oval and Waterloo railway station, in a house called Ivy Cottage, the home of a publican called John Parker.

Keep your love of nature, for that is the true way to learn to understand artVincent Van Gogh

Vincent returned to his old job at Goupil (now in new offices at 25 Bedford Street, around the corner from the old shop on Southampton Street) but by now his interest in this fledgling career had waned. He still didn’t aspire to become an artist, but he’d started thinking like an artist.

“Try to take as many walks as you can and keep your love of nature, for that is the true way to learn to understand art,” he wrote to Theo. “Painters understand nature and love her and teach us to see her.” This is clearly an aspiring artist talking, whether he realised it yet or not.

Vincent did several drawings during his time in London, including a sketch of 87 Hackford Road. This didn’t mean he saw himself as an artist. Before photography became commonplace lots of people drew - it was like taking photos on a smartphone. Even so, these are some of Vincent’s earliest works - and it’s notable that they’re of London, not his native Netherlands.

In the spring of 1875 Vincent was transferred to Goupil’s head office in Paris. For an ambitious youngster this should have been a step up, but Vincent had long since lost all interest in becoming an art dealer. He’d decided he wanted to be a schoolteacher, ideally in Britain.

In December he left Goupil, for good this time, returned to his parental home in Holland, and scoured the English newspapers for adverts for suitable positions. The only opening he could find was an unpaid post at a school in Ramsgate.

Vincent van Gogh was accompanied by his sister Anna on his second trip to London and frequently sent correspondences to his brother Theo conveying his thoughts about the UK’s capital.

Vincent arrived in Ramsgate in 1876 and took to this rugged seaside town straight away. “These are really happy days,” he wrote to Theo. “It’s beautiful here.” The school was located at 6 Royal Road, overlooking the promenade and the bustling harbour beyond. Vincent sketched the seafront from the school’s bay window. The building is still there today. Although he received no salary, the school gave him board and lodging, housing him in a rented room at 11 Spencer Square, a short walk away.

However the school itself was a mean affair – 24 boys, aged 10-14, housed in a dormitory with broken windows and a rotting floor. The proprietor, a Mr Stokes, left the running of the school to his 23 year-old son (the same age as Vincent) and an assistant who was just 17. Vincent taught Maths and French, though his teaching must have been pretty rudimentary. Although he was a voracious reader, he’d never shone at school.

In July 1876 Mr Stokes transferred his school to Isleworth, in West London. Vincent went with him. Isleworth is a leafy suburb now, but it was a working class district then. Located on the River Thames, today it’s a pleasant place to wander, but then it was crowded with docks and wharves, like a scene from Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend. Vincent always championed the poor and needy - here he saw the poor and needy at first hand.

In his free time, Van Gogh visited Hampton Court (a brisk walk away, along the river) and admired the Rembrandts, Holbeins and Bellinis there. “It was a pleasure to see pictures again,” he told his brother.

Vincent soon found a slightly better job at another school nearby, run by a Reverend Jones, who sounds more respectable than Mr Stokes. Impressed by his religious zeal (and possibly less impressed by his rudimentary teaching), the Rev Jones arranged for him to take the Sunday School at Turnham Green - a wealthy district nowadays, but proletarian back then.

The Reverend Jones also encouraged his ambitions as an itinerant preacher. Soon, Vincent was delivering sermons all over London. “Tomorrow I must be in the two remotest parts of London,” he wrote to Theo. “In Whitechapel, the very poor part that you have read about in Dickens, and then across the Thames in a little steamer and from there to Lewisham.”

Vincent returned to the Netherlands in December 1876. He never returned to Britain. His work for the Reverend Jones had inspired him to become a pastor. From the Netherlands he went to Belgium, to teach the impoverished miners of the Borinage the Good News about the Son of God. When that vocation failed he finally turned to painting. The rest is Art History.

You can retrace Vincent’s steps all over London, from the galleries he visited to the places where he stayed. The highlight is 87 Hackford Road, which is currently being renovated, as a centre for young artists and writers.

The school across the road has been renamed the Van Gogh School, and there’s even a Van Gogh Walk, through a cul-de-sac that’s become a garden. “I walk here as much as I can – it’s absolutely beautiful, even though it’s in the city,” Vincent wrote to Theo. “There are lilies, hawthorns and laburnums blossoming in all the gardens, and the chestnut trees are magnificent.”

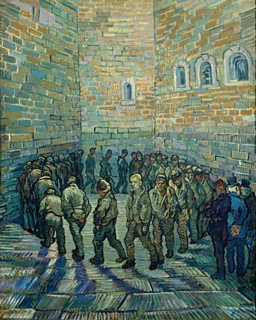

Vincent never painted these trees and flowers (his only painting of London was Prisoners Exercising, a metaphorical self-portrait inspired by a Gustave Doré engraving of Newgate Prison) but London planted a seed in him that grew and grew. The trees and flowers he painted a decade later, across the Channel in France, would change the course of modern art.

is at Tate Britain, London, from 27 March to 11 August 2019.

Related Links

Current exhibitions

-

![]()

Streetwise art

How Keith Haring made New York City his canvas.

-

![]()

London calling

How the capital inspired Vincent van Gogh.

-

![]()

The original emoji

Why The Scream is still an icon for today.

-

![]()

Da Vinci decoded

See the Renaissance master's drawings in twelve UK cities.

More from 91�ȱ� Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms