Earth from Space – Explained

Before I start I should state for the record that I am not a remote sensing expert.

by Chloe SaroshSeries Producer

Far from it.

I am a television producer who was lucky enough to work with remote sensing experts and as such I will keep the technicalities to their most basic to avoid upsetting them!

We have had such an overwhelming response to the series with so many people asking how we achieved some of the shots, that I thought I might walk through the process behind some of the sequences that were the most challenging and how we accomplished them.

Time-lapse

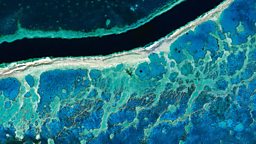

This was something that we only realised we could achieve whilst making the series. We started with before and after shots, for example the images of coral bleaching on the Barrier Reef in episode 3. Then we realised that we could show more gradual change by asking the satellite companies to take images for us of the same area over days, weeks and months. By combining these images we can show snow cover the Himalayan Mountains where the snub-nose monkeys live or the rapeseed bloom transform the Chinese landscape. We did this in exactly the same way you would create a photographic time-lapse; line the images up so they match exactly, take out any images that are of poor quality and then combine them to create a moving image.

In the case of the Amazon River in episode 2 we needed to go back further and so we used NASA archives as their satellites have been taking pictures for decades. By combining the images of the same section of river taken over ten years, removing any where cloud obscured the view (it’s the Amazon, it rains a lot!) we could show the river’s tributaries twisting and turning to form oxbow lakes.

Perhaps the most arresting time-lapses are of cities growing and forests disappearing in episode 4. We can see the planet changing right in front of our eyes. Lining up such detailed images that change so dramatically year by year is incredibly challenging. We were grateful to the Google Earth Imaging team for their expertise in achieving this.

I am not a remote sensing expert.

Super Zooms

We knew we wanted to deliver some epic zooms from way out in space, right down to the ground. These were undoubtedly our biggest challenge.

First a bit of (very basic) background on the different images satellites are taking. There are cameras that are way out in space taking images of the whole Earth. Then there are satellites that are taking images that are a bit more detailed - continents and countries. These images are ‘stitched’ together to cover larger areas of the globe (these are the kind of shots of the planet we’re used to seeing from NASA and ESA) and then there are the super high-resolution cameras that can show incredible detail.

We knew that, in theory, the resolution of the very best satellite imagery is such that if we zoomed right into the image we could then create a seamless ‘take over’ with a drone to finish the shot. Theory and practice are of course very different things! The satellite has to be programmed to capture the exact spot that the drone is also filming. The drone needs to be filming at the right moment. Clouds get in the way, the light changes, it rains and the drone can't fly, all sorts of things can and did go wrong BUT we were also very lucky.

In the case of the elephants in episode 1 we zoom all the way in from a continent view. To achieve this we move through at least two different satellite images, from Africa as a recognisable whole into the more detailed image that captured the elephants and finally into the drone shot. The result is pretty mind-bending.

Of course the satellite only goes over once each day and takes a single image which is an extra pressure. In episode 3 there is a beautiful zoom from satellite to drone over tulip fields in the Netherlands. We had to film for several days to make sure that we had the satellite and drone matching exactly. We were more lucky with the Kung-Fu sequence in episode 1. This whole sequence was incredibly challenging as the performance lasted less than 25 minutes. We had three cameras on the ground, a drone in the air and the satellite camera. However with all of this and a clear sky we still only had a single shot from space. The satellite company later informed us that they had taken a shot of the same display at another date which (as we’d filmed the sequence on the ground and knew the satellite image to be true to the display) allowed us to show a second ‘hit’ of the routine from space later in the sequence.

We also had a lot of help from scientists who are using this technology to study the planet. In episode 3 the British Antarctic Survey guided us to single satellite images that we were able to zoom through to find individual albatross and another of the blood on the ice of birthing Weddell seals. These are pinpricks of colour in a huge image. Amazing.

Stef Lhermitte from Delf University provided us with drone mapping that reveals the extent of the blue lakes on the ice shelf also in episode 3. Due to the weather conditions and orbit of the satellites, Arctic imagery is slightly harder to come by and we didn’t have a close, detailed shot of the lakes. He had mapped hundreds of drones images to create a single shot of the area, this mapping allowed us to zoom right in from satellite to a single lake.

In short, doing something new is challenging and sometimes a little daunting but we had help from brilliantly knowledgeable people who were generous with their expertise. We couldn’t have achieved this series without them.

Of course the satellite only goes over once each day and takes a single image which is an extra pressure.