Busting the myth

Florence Nightingale was so much more than a lady with a lamp. The legend of the saintly nurse has long obscured the truth ‚Äď that her mathematical genius was what really saved so many lives.

Her ambition led her into the hellish world of Crimean warfare and, as a result, on a journey that would transform nursing and hospitals in Britain.

1820

A gifted child

Florence was named after the Italian city of her birth. She grew up on picturesque English country estates with her elder sister, Parthenope.

Her upper middle class upbringing included an extensive home education from Florence‚Äôs father, who taught his daughters classics, philosophy and modern languages. Florence excelled in mathematics and science. Her love of recording and organising information was clear from an early age ‚Äď she documented her extensive shell collection with precisely drawn tables and lists.

1837

Florence hears God

The Nightingales took their daughters on a tour of Europe, a custom intended to educate and refine gentlewomen in the 19th Century.

But Florence's unconventional character continued to develop, as entries from her diary of the trip show. She recorded detailed notes of population statistics, hospitals and other charitable institutions. In spite of her mother's disapproval, she later received further tuition in mathematics. Yet her biggest rebellion was still to come. In 1837, she became convinced God had 'called' her to his service but her parents were horrified when she revealed what she thought the service should be…

1844

A proposal

Florence was an eligible young woman ‚Äď intelligent, striking and wealthy. Proposals were sure to come her way, but Florence had a proposal of her own.

Her family expected her to marry well but the prospect of a life of domesticity left Florence cold. By 1844, she had decided nursing was her calling. She proposed training in Salisbury, but her parents refused. They thought nursing was lowly, immodest work done by the poor or servants, completely unsuitable for a woman of Florence’s social standing. Florence, however, persevered. In 1849, after a long courtship, she even declined a proposal of marriage, believing her destiny lay outside wedlock.

1853

The breakthrough

Nothing could sway Florence from her mission to nurse. She defied her parents' wishes and continued to visit hospitals in Paris, Rome and London.

In 1850, realising his daughter was unlikely to marry, Florence’s father finally relented and allowed her to train as a nurse in Germany. Parthenope struggled to accept her sister’s hard-won independence and suffered a nervous breakdown in 1852. This forced Florence to return and care for her. But in August 1853, the breakthrough finally came: Florence became superintendent at a women's hospital in Harley Street. After nearly a decade, she had realised her ambition of becoming a nurse.

1854

The Crimea calls

The Crimean War broke out in 1853. Newspaper reports from the front line told horror stories of the appalling conditions in British army hospitals.

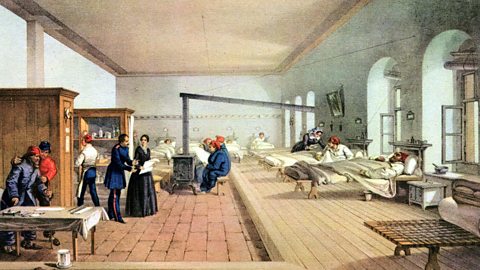

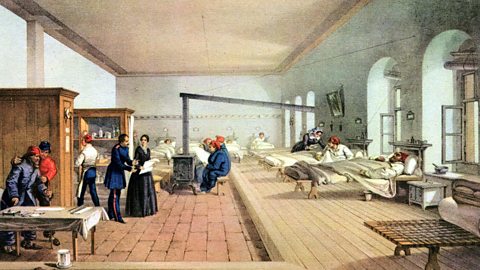

Sidney Herbert, Secretary of State at War, knew Florence well. He appointed her to take 38 nurses to the military hospital in Scutari, Turkey. It was the first time women had been allowed to officially serve in the army. When she arrived, the Barrack Hospital was filthy ‚Äď the floor was an inch thick with faeces. She set her nurses to work cleaning the hospital and ensured soldiers were properly fed and clothed. The regular troops were, for the first time, being treated with decency and respect.

1855

The death toll rises

Florence’s best efforts to combat the rising death toll failed. It kept increasing relentlessly, with over four thousand deaths in a single winter.

Although she had made the hospital more efficient, it was no less deadly. In the spring of 1855, the British government sent out a sanitary commission to investigate the conditions at Scutari. It discovered the barrack hospital was built on a sewer, meaning patients were drinking contaminated water. The hospital, along with other British army hospitals, was flushed out and ventilation improved. Consequently, the death rate began to fall.

1855

The lady of the lamp hits the big time

When a portrait of Florence carrying a lamp and tending to patients appeared in the press, she quickly gained an army of die-hard Florence fans.

Her work in Scutari improving the living conditions of soldiers in hospitals was hailed by both the press and the public. Her family had to wade through a steady stream of poems posted to Florence ‚Äď the Victorian equivalent of fan mail ‚Äď and images of 'the lady of the lamp' were printed on bags, mats and souvenirs. But Florence was wary of her celebrity. Although she returned home a heroine, she kept a low profile by travelling under a pseudonym ‚Äď Miss Smith.

1856

Florence gets to work

It wasn't until after she had processed all she had learned at Scutari, that Florence used her fame as a powerful weapon in her mission to save lives.

Haunted by the appalling loss of life, Florence met with one of her biggest fans, Queen Victoria. With her backing, she persuaded the government to set up a Royal Commission into the health of the army. Leading statistician William Farr and John Sutherland of the Sanitary Commission helped her analyse vast amounts of complex army data. The truth she uncovered was shocking ‚Äď 16,000 of the 18,000 deaths were not due to battle wounds but to preventable diseases, spread by poor sanitation.

1857

Florence reveals the truth

Florence knew her talent for statistics wouldn't be enough to ensure her report hit home. It was time to prove her mastery of communication as well.

Rather than lists or tables, she represented the death toll in a revolutionary way. Her ‚Äėrose diagram‚Äô showed a sharp decrease in fatalities following the work of the Sanitary Commission ‚Äď it fell by 99% in a single year. The diagram was so easy to understand it was widely republished and the public understood the army‚Äôs failings and the urgent need for change. In light of Florence‚Äôs work, new army medical, sanitary science and statistics departments were established to improve healthcare.

Professor Marcus Du Sautoy explains the rose diagram. Clip from The Beauty of Diagrams (91»»Ī¨ Four, 2010). Image: Florence Nightingale Museum/Bridgeman.

1870

Healthcare for everyone

Florence was ill but wealthy ‚Äď she could afford to pay for private healthcare. But she knew most people in Victorian Britain couldn't do the same.

Impoverished people could only care for one another. Florence's Notes on Nursing aimed to educate people about ways to care for sick relatives and neighbours, but she still wanted to help the very poorest in society. She sent trained nurses into workhouses to help treat the needy. This attempt to make medical care readily available to everyone, regardless of their class or income, served as an early precursor to the National Health Service.

1880

Florence takes the fight to India

Florence had been involved in improving the health of the British army in India since her experiences in Scutari.

By the 1880s, scientific knowledge had advanced to further support her reforming ideas. Like many medical practitioners, she now accepted germ theory, and so emphasised the need for uncontaminated water supplies for people in India. Still collecting data, she campaigned for famine relief and improved sanitary conditions to combat a high death toll that she believed was caused by conditions akin to those she’d witnessed in Scutari. Florence received reports from India until 1906.

1910

Florence dies

Before Florence died at the age of 90, she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit.

The headstrong girl with a well-documented shell collection had achieved so much, in a field once deemed unsuitable for women of her class. Often a lone female voice appealing to the Victorian establishment, her skill for communication and mathematics helped overhaul army and civilian healthcare and saved thousands from a gruesome death. She shrewdly used her public mandate to urge governments into action, enshrining sanitation and personal well-being in our healthcare culture.

Where next?

Florence Nightingale. video

Florence Nightingale tells the story of her life and how she grew up to become a nurse.

Nurturing Nurses. collection

The history of nursing, including Florence Nightingale, Mary Seacole, Edith Cavell and the NHS.

Florence Nightingale: The founder of modern nursing. video

A short film about Florence Nightingale and the work she did to transform nursing during the Victorian era.