Spartak and survival - the story of Nikolai Starostin

- Published

As Celtic fans watch their Champions League opponents, Spartak Moscow, take to the field, almost all will know former Celt Aiden McGeady.

Most will probably be aware they are facing Russia's most successful club.

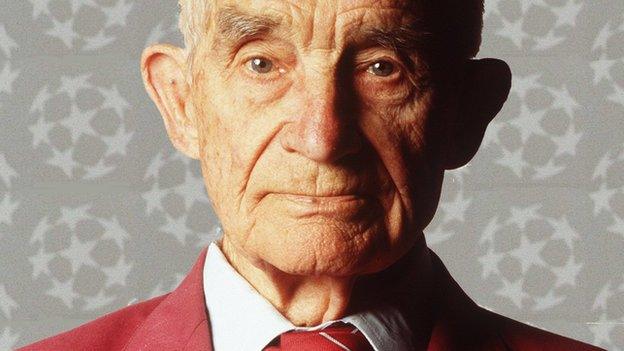

But few will know the dramatic life of Nikolai Starostin, the man who created, almost singlehandedly, Russia's most popular club.

The turmoil of the revolutions of 1917 and subsequent civil war left little time to think of football, but for one young Muscovite it was a matter of survival.

Starostin, the oldest of four brothers, became the breadwinner for his family when his father died in 1920.

A talented sportsman, he earned a living playing football in the summer and ice hockey in the winter - becoming Soviet captain in both sports.

The USSR of the 1930s worked on a system of patronage and Starostin found his in Alexander Kosarev, head of the Komsomol youth organisation.

Kosarev saw political benefits in being associated with football success and, when Starostin suggested forming a club for food workers, he backed the idea and Spartak were born.

Football in the USSR saw clubs associated with particular state ministries - CSKA were the army team, for example - but Spartak remained a voluntary sport society.

As such, supporting Spartak came to be viewed as a minor act of disaffection.

However, as well as making powerful friends, Starostin had also made a powerful enemy.

Lavrentii Beria was the head of the NKVD, Stalin's feared secret police and a man to be feared.

Beria was a football fan, and head of the Interior Ministry-affiliated Dinamo sports society, whose teams, particularly Dinamo Moscow, dominated Soviet football.

With one club representing the secret police, and one representing the voice of dissent, a fierce rivalry was inevitable.

However, claimed Starostin, there was a more personal nature to the grudge.

He recalled beating a Georgian team in the 1920s which featured a 'crude and dirty left half', one Lavrentii Beria.

The new team quickly became the top Soviet club when leagues were established in the USSR in 1936 - previously, competitive sport had been viewed as unsocialist - winning league and cup doubles in 1938 and 1939.

In the late 1930s Stalin's purges reached their peak, as millions of Soviet citizens were arrested, sent to the Gulag - or, all too often, executed.

As the Komsomol was purged in 1938, Kosarev was arrested and shot.

Without his powerful patron Starostin was isolated, and Beria soon showed his power.

After Spartak defeated Dinamo Tbilisi in the semi-final of the 1939 Soviet Cup, Spartak beat Stalinets Leningrad 3-1 in the final.

Beria was not going to let the defeat of his favourite team go unpunished, and a replay of the semi-final was ordered - after the trophy had been presented.

The original referee was arrested, but Spartak still triumphed, beating Tbilisi 3-2, much to Beria's chagrin.

"When I glanced up at the dignitaries' box, I saw Beria get up, furiously kick over his chair and storm out of the stadium," recalled Starostin.

One night in 1942, Starostin states, he awoke to a pistol being held to his head; Beria was to take his revenge.

The brothers spent two years in the feared Lubyanka prison in Moscow, before being sentenced, on what Starostin claims was a charge of 'praising bourgeois sport', to 10 years' hard labour.

However, there is evidence that he was actually convicted on charges of fraud - a not uncommon practice in Soviet times.

The labour camps were harsh, brutal places in Siberia or the Arctic north, with fatality rates of up to 30% in some camps.

However, for the second time in his life, football was to prove key to Starostin's survival.

As a famous sportsman, he found camp authorities wanting him, ironically, as coach for local Dinamo teams.

This allowed Starostin better rations and he was allowed to sleep at the club's training ground rather than in the grim barracks.

Starostin's life took another strange turn in 1948, when he was summoned to the phone to take a call from a Red Air Force general - Stalin's son Vasilii.

Vasilli had an air force team, VVS, and brought Starostin to Moscow to coach it.

Beria, however, had other ideas, and Starostin was forced to move into the younger Stalin's house for protection.

A game of cat and mouse between the two powerful figures ended with Starostin exiled to Kazakhstan, to coach Kairat Almaty.

After Stalin's death in 1953 an amnesty for some political prisoners was announced and Starostin was freed.

Finally, in 1954, 12 years after his arrest, he returned to his city and his club, as president.

Starostin remained at the helm of the club until 1992, dying in February 1996 with the club he had formed going on to win that season's Russian title.

- Published3 December 2012

- Published12 February 2013

- Published6 December 2012

- Published1 December 2012

- Published26 November 2012

- Published23 November 2012