Fearfully and Wonderfully Made

From Three Ways School in Bath, a specialist school that gives young people physical and sensory support and workplace of singer, composer and music therapist Adrian Snell.

'Fearfully and Wonderfully Made.' From Three Ways School Bath - a Specialist School for Physical and Sensory for young people from 3 to 18, and work place of singer and composer Adrian Snell. Adrian's albums have sold half a million copies to an eclectic audience worldwide, but he also works as a music therapist with young people with special educational needs. Preacher: The Revd Martin Lloyd Williams.

In the 1980s, Adrian's Easter and Christmas rock operas The Passion and The Virgin were premiered on 91�ȱ� Radio 1. Today he works as a music therapist and Arts Therapy Consultant at Three Ways, a special needs school in Bath, from where Sunday Worship will be broadcast.

Adrian's music room at Three Ways is a world away from the concert stage and recording studio, but he says he has no regrets about his transition from international performer to music therapist. 'This has been the most important step in my career as a musician', he says, 'many of us describe music as 'the language of the heart'. 'In the world of special needs, where many of our children are either unable to communicate through the spoken word, or choose not to do so, the idea of music as a language takes on a deeper meaning.'

The son of a bishop and the godson of an Archbishop of Canterbury, Adrian is challenged in another way, 'I find myself asking why are people with special needs so under represented in our churches and Christian communities? We have failed to offer a theology of inclusion, both practically and spiritually. One of the great privileges I have as a music therapist is that I am focusing on what our children and young people CAN do, beyond their limitations.'

This special edition of Sunday Worship will 'drop in' on sessions where music therapy techniques, are used. Interspersed between these moments, the programme will feature songs from Adrian's new album 'Fierce Love', which was inspired by the children he works with and features the extraordinary range of instruments he uses as a therapist.

The service includes a reflection by The Revd Martin Lloyd William's, who until recently had a son at Three Ways School, as well as prayers and readings. Martin openly shares his personal experience, and reflected theology, of bringing up a son with Downs Syndrome.

This edition of Sunday Worship will be broadcast at 8.10 am on Sunday on Radio 4 and available afterwards on iPlayer.

Last on

Clip

-

![]()

The making of Three Ways Sunday Worship

Duration: 03:48

Fearfully and Wonderfully made

Sermon - The Revd Martin Lloyd Williams

��I can remember the day when our son, Benedict Peter was born. 12 July 1992. I looked at him for the first time and I thought something was not as it should be. Ben's eyes in particular suggested something to me. I asked the midwife if she thought there was anything to worry about but she reassured us that all was fine. So we telephoned the family to say that a beautiful boy had arrived. A little later I left to fetch some things and on my way back overheard the nurses at the reception desk talking about a newly arrived baby on the ward who had Downs Syndrome. I think I knew who they were talking about. Not long after, that the paediatrician arrived and said he wanted to examine our baby. He looked for the deeper than usual creases across the palm of his hand. He felt his head for an additional soft spot. He pointed out the large gap between his big toes and the rest of his toes. He was very kind as he told us that in all probability Ben had Downs Syndrome.

��

At that moment everything had changed and yet nothing had changed. This was not the baby we had expected.�� Then we telephoned the family once again.

��

There were so many questions. A bomb had exploded somewhere in our future which changed the horizon rather a lot. But in that present moment, the three of us in the maternity unity, all was peaceful. And then we went home.

��

We were surrounded by love from family and friends and then we chose some godparents with care. One of them, James, had been praying for us and then stumbled across a book of renaissance art, which he sent to us. In it was a depiction of the Presentation of Christ at the Temple by the early renaissance artist Andreas Mantegna. He had painted in many ways a standard piece of religious art: serious, deliberate and reflective. But it was startling in one aspect. Mantegna had painted the baby Jesus seemingly with Downs Syndrome.������

��

As you can imagine, my first reaction was to be deeply moved. God knew and understood our situation! And this painting did not just speak of God's presence with us, it also made a profound statement about the inherent dignity and worth of all people with learning disabilities.

��

To this day, having researched the painting, I cannot get inside the artist's mind, I don't why he painted Jesus in this way, but one thought led to another. And this is what struck me. Babies with Downs Syndrome, grow into toddlers, who grow into children and then teenagers and adults with Downs Syndrome. And I doubt that this was in Mantegna's mind, but in my mind was the question: could God have become incarnate in the world, personally present in the world, by becoming a person with a learning disability? Could that have happened? Would a disabled incarnation in some way have prevented the will of God from unfolding?

��

Well, if the purpose of Jesus is defined primarily in terms of a task he had to achieve or a solutions he had to bring about, then it is difficult to see how he could have been successful had he been born with a learning disability. But might there be another way of understanding things? What if we open ourselves to the possibility of recognising a creator who is so passionate about his creation that he quite literally throws himself recklessly into it in the incarnation. Might he do such a thing not simply because he wants to effect a particular result, but because he cannot bear to be apart from it, because he is intrinsically bound up with its destiny, because it is his very nature to continue to pour himself out?

��

If this whirlwind of Godly passion has as its primary desire the intention of drawing all creation and all creatures back to the source of all life, is it not possible to see a deeper process at work that we need not so much to explain as to be caught up in? And if this is the case, if God's desire is to elicit from us reciprocal love and fierce devotion, maybe it is also important for him to be incarnate in a way that draws out of us an equally selfless love that, in the first instance at least, offers no guarantee of material reward. If God is calling us firstly to love him for himself, rather than with the intention of our obtaining something, what better way to come among us than as a person with learning disabilities, a person so reliant and dependent on other people.

��

In his letters from prison, Deitrich Bonhoeffer wrote this: "God lets himself be pushed out of the world onto the cross. He is weak and powerless in the world and that is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us. Matthew 8.17 makes it quite clear that Christ helps us not by virtue of his omnipotence, but by virtue of his weakness and suffering. . .only the suffering God can help. . .that is a reversal of what the religious person expects from God. People are summoned to share in God's sufferings at the hands of a godless world."

��

The powerlessness of God is uncomfortable and even disturbing. Alarmingly the God described by Bonhoeffer does not so much provoke anger as risk being simply ignored, placed, as it were, in a care home, forgotten, easy to patronize, easy to think of as an object for pity. He becomes therefore like so many with a learning disability.

��

But just as the world attempts to treat Jesus in this way, having managed to entomb him figuratively but safely in a residential care establishment, we come back the following morning and find that the doors have been completely blown off and the residents all gone! Somehow, in the choice the Son of Man makes to identify with the least of the least, God does far more than say, "there there, I know how it feels." In choosing to become the least of all, Jesus subverts the world, fulfils his divine destiny, and sets free all those captives who agree to join him in the Great Breakout that we call redemption. But the world had to be subverted first. The Son of God had to come as one needing not only to give out the heavenly invitation but to receive it, to actually receive God's heavenly invitation to new life, on behalf of a world that for so long had been unable even to get dressed for the heavenly party.

��

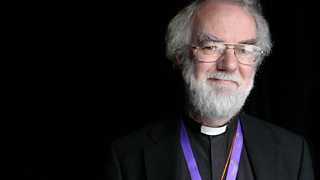

I am fearfully and wonderfully made says psalm 139. Yes you are! And you can show this to be true not by being faster, stronger, clever, or more powerful than the next person, but by forging a connection with those who, you may believe, have nothing to offer you. Rowan Williams said: "How deeply depressing if all the Church offered were new and better way of succeeding at the expense of others." What Adrian's work illustrates, what psalm 139 speaks of, what Jesus is about, is not success at the expense of others, but abundant life that includes everyone.

��

The world of learning disabilities can be vivid, intense and raw as you may have discovered this morning, maybe that is also why the love found here is a fierce love, a love that reflects the love of God himself.

��

��

��

Music list

��

By Adrian Snell.

"Our Father", setting of "The Lords Prayer " from "The Cry", by Adrian Snell

��

Night and Day, Sometimes the Broken Hearted, Fierce Love, Grateful – All from the album ‘Fierce Love’

��

Commotion in the Ocean- specially recorded at the school

��

Hazel: - specially recorded at Three Ways School by Adrian and a pupil.

��

By the Rivers of Babylon – specially recorded at Three Ways School by Adrian and the school choir (Writers: Dowe, Brent - Boney M, 1978) ��

Broadcast

- Sun 6 Oct 2013 08:1091�ȱ� Radio 4