The most extraordinary skin on the planet

Skin is the body’s largest organ. It has allowed vertebrates to conquer virtually every habitat on the planet by growing hair, feathers, scales and even teeth.

In Secrets of Skin, Professor Ben Garrod explores the latest science and puts his own skin under the spotlight to reveal the layers of the multi-purpose barrier that keeps the outside out and the inside in.

Read on to reveal six groups of animals with truly remarkable skin…

What fascinates me most about skin is that we still have so much more to find outProfessor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

Frogs: Thin skinned... but feisty!

Frogs have some of the thinnest skin of all vertebrates and with very good reason….they breathe through it. Their skin has evolved to let oxygen pass through the cells of the epidermis and dermis and into the blood stream and frogs can get up to 20% of the oxygen they need in this way.

Being thin skinned has an advantage for one group of frogs when it comes to defending themselves. Tiny poison dart frogs are one of the most toxic groups of animals on the planet. They secrete a very potent poison through their skin, the brighter the frog the more toxic the poison.

One toxin, epibatidine attacks nerves, causing numbness and paralysis. Researchers hope that by unpicking epibatidine’s structure and chemistry they may be able to separate its from its deadly toxicity.

Scientists are studying the deadly chemicals these frogs deploy in order to design new pain killing drugs and medicines.Professor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

One of the most toxic skins on the planet

The skin of wild poison dart frogs is deadly due to the animals they eat.

Sharks: Skin that's built for speed

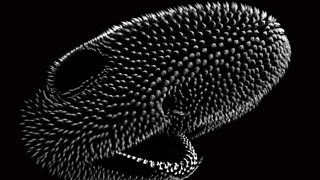

Sharks are some of the most formidable hunters in the oceans, with some species reaching top speeds of over 64 Kilometres per hour. Their skin plays a crucial role in helping them do this. They don’t achieve a super hydrodynamic surface to their skin by being smooth, quite the opposite.

Shark skin is covered in tooth like structures called denticles made from a very similar material that human teeth are made from. The key are riblets, peaks and troughs on the surface of the denticles that reduce the friction of the swirling fluid above the surface of the shark’s skin making them slip through the water super fast.

The shark in this incredible image is only a few weeks old but you can already clearly see the regular arrangement the denticles form in the skin.

If you look at the skin of a shark in microscopic detail you’ll see their skin is effectively covered in millions and millions of tiny teeth.Professor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

The hydrodynamics of shark skin

How dermal denticles help sharks to quickly travel forwards through water.

Hippos: Skin with built in sun protection

UV rays from the sun are one of the most dangerous things the environment throws at the animal world and they are just the right wavelength to damage the skin’s fragile DNA, causing skin cancer. Animals need to find a way to stop UV reaching their skin cells, and a physical obstacle like fur or feathers is brilliant. But if you’re as hairless as a hippo how do you protect yourself from the damaging effects of UV?

One tactic is to spend the day wallowing in mud and water, although it’s hard to completely submerge such a big body, so there’s always a bit of skin in the full glare of the sun – but hippos never get sunburnt.

Hippo skin produces thick red droplets of fluid, known as ‘blood sweat’. When Scientists analysed this blood sweat they discovered it’s not blood or actually sweat, but instead is an oily mixture of water repellent, antibiotic and a UV-blocking chemical that turns red in sunlight.

Hippo skin makes its own sunscreen!Professor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

Atlantic puffins: Skin with a secret code

Puffins are unmistakable with their brightly coloured beaks that they sport during the summer months when they come to land to breed. But there’s something hidden in the skin on their beaks that the human eye can’t see.

Jamie Dunning, an ornothologist, shows Ben a revealing the beak glows with fluorescence. And the reason? Unlike humans who can only see 3 types of colour: red, green and blue, birds have a fourth which allows them to some degree to see in UV light.

The fluorescence on a puffin’s beak only occurs during the breeding season, it drops off during the winter, leading Jamie to conclude that puffins use this secret method of communication to lure in the opposite sex.

It’s amazing, these little birds that we kind of grow up knowing so well, actually have a load of secrets in their skin that we didn’t know before.Professor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

Puffin beaks glow in the dark

Jamie Dunning from Imperial College London has made a remarkable puffin discovery.

Porcupines: The prickliest skin

When it comes to using quills as a weapon the champions have to be porcupines.

A predator like a lion, capable of taking down a 900kg eland, is no match for 30kg of well-defended African porcupine. These big and impressive quills have evolved to be detachable. And just like hair, they fall out from the skin without harming the owner at all.

The smaller quills of the North American porcupine may look underwhelming in comparison, but appearances can be deceptive. In the clip below Ben demonstrates how by stabbing a quill from a North American porcupine into a piece of chicken. It goes in nice and easy, but pulling it out is a different matter. The quill embeds itself into the flesh thanks to its backward facing microscopic barbs…the ultimate defence against attack.

If a porcupine impales an attacker, the lost quills will grow back in a matter of months – while the predator learns a valuable lesson.Professor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

The defensive spines of a porcupine

Porcupine spines are enough to deter the most dangerous of predators.

Crocodilians: Super sensitive skin

As some of our planet’s most formidable hunters Crocodilians sit at the top of the food chain, but they didn’t get to be the apex predators they are by simply using brute force. The real secret to their success is hidden in their skin.

Ben heads to the UK's only crocodilian zoo just outside Oxford for feeding time with some very hungry Nile crocodiles and to set up an experiment to show just how sensitive crocodilian skin is.

Placing a baby alligator into a tank, Ben drops pieces of meat through tubes into the water, so the alligator can’t see where the food is coming from. As the food hits the water, it creates tiny ripples and within a fraction of a second the alligator turns towards the food. It does this through hundreds of tiny dome shaped pressure sensors on its snout. Underneath each dome is a network of nerve fibres that are able to detect the tiniest of movements in the water. It’s a brilliant hunting tactic, meaning crocodilians don’t have to rely on their eyes in murky water, deploying their super sensitive skin instead.

I’m suddenly feeling less confident…..because they can jump as well!Professor Ben Garrod, Secrets of Skin

Watch Secrets of Skin on 91�ȱ� iPlayer

-

![]()

Adaptability

Professor Ben Garrod explores how versatile the basic skin structure truly is, revealing how slight adaptations have created birds' feathers and a rhinoceros’s horn.

-

![]()

Moving

What makes sharks built for speed? How do snakes move without limbs? How do sugar gliders fly without feathers? The answers all lie in their skin.

-

![]()

Protection

Professor Ben Garrod reveals how skin protects vertebrates from extremes of temperature, the harmful effect of UV and a host of living organisms that want to get in.

-

![]()

Communication

Professor Ben Garrod explores how skin has evolved remarkable ways to enable animals to communicate with each other, from vibrant displays of colour to skin pouches to amplify sound.

-

![]()

Defence

What is the most toxic animal on earth? Why is a rhino armour plated? Professor Ben Garrod discovers the complex ways in which skin helps defend animals against threats of all kinds.

-

![]()

Sensing

Professor Ben Garrod explores how some snakes can see using heat, how crocodiles feel through their jaws, and how some animals use electricity to navigate their world.