What can novels tell us about how men and women respond to a crisis?

27 October 2020

The Covid-19 pandemic has raised questions about whether male and female leaders respond differently in times of uncertainty. PROFESSOR SEBASTIAN GROES and PROFESSOR KARINA VAN DALEN-OSKAM think their new study of novels about power and politics might give us a clue.

Image: Angela Merkel and Jacinda Ardern (Alamy)

Recently, news stories from a range of sources including and argued that countries led by women have handled the Covid-19 pandemic better than those led by men.

The NYT singled out leaders such as Jacinda Ardern and Angela Merkel for a ‘new leadership style’ that avoids bias, groupthink and blind spots by making use of many different sources of information.

This is a provocative claim. The same papers took pains to point out that dividing leaders into homogenous groups of men and women is not necessarily helpful. However, it raises interesting questions about whether - and why - there might be differences in the way that men and women react to moments of political upheaval.

Why turn to literature?

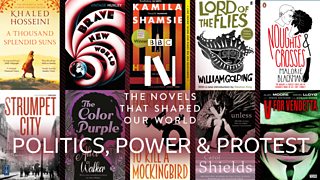

Recently, a panel of authors and literary experts selected ten novels about power, politics and protest that shaped their world. Re-reading these and other novels – and using innovative computational analysis – has highlighted differences between the books written by men and women.

We can ask why this might be the case. Do men and women use language differently? Have the unequal opportunities faced by women – in literature as in politics - led them to adopt different strategies in public spaces dominated by men? Or do publishers and panelists choose to recognise different kinds of fictions from authors of different genders?

Seeking answers to these questions may throw new light on different political responses.

The Novels That Shaped Our World panel chose ten novels on ‘Politics, Power & Protest'. From left to right: Stig Abel, Mariella Frostrup, Juno Dawson, Kit de Waal, Alexander McCall Smith and Syima Aslam.

- A Thousand Splendid Suns – Khaled Hosseini

- Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

- 91�ȱ� Fire – Kamila Shamsie

- Lord of the Flies – William Golding

- Noughts & Crosses – Malorie Blackman

- Strumpet City – James Plunkett

- The Color Purple – Alice Walker

- To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

- Unless – Carol Shields

- V for Vendetta – Alan Moore

Seeing differently

The 91�ȱ� novels address a broad range of conflicts. Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta focusses on oppressive government. Malorie Blackman's Noughts & Crosses imagines a world in which Africans have enslaved Europeans. Khaled Hosseini's A Thousand Splendid Suns is an analysis of women in Afghanistan. This eclectic selection shows there’s no such thing as feminine and masculine subject matter.

However, there may be differences in the way men and women approach these topics. Some authors take on political events and regimes directly. James Plunckett’s epic Strumpet City traces the lives of a dozen (mostly male) Dubliners during the violent 1913 Dublin Lock-out, and does not shy away from explicit descriptions of poverty. William Golding’s Lord of the Flies is an analysis of politics and violence among young men.

By contrast Carol Shields’ Unless is steeped in gender politics, but also a beautiful, introspective meditation on ordinary lives. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird reveals stark truths about racism, but focuses on how these injustices are perceived by children.

In her essay ‘Women and Fiction’ (1929), Virginia Woolf argues that women have different values to men, allowing them to undermine male-dominated ideology and convention by expressing themselves differently.

A Room of one's own

Responding too quickly

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 have inspired many novels. A recent book made the bold claim that male and female authors have responded differently. Women tended to write about 9/11 indirectly, through form, style, imagery and symbolism. Men, to put it crudely, were more likely to show falling bodies and crashing planes.

Men including Philip Roth, John Updike, Don DeLillo, Martin Amis and Jay McInerney often represented the event soon after the attacks. Many women withheld their responses. Lionel Shriver withdrew her novel The New Republic because she felt the depiction of violence might upset readers.

In the 91�ȱ� list, Kamila Shamsie’s 91�ȱ� Fire was published more than a decade after 9/11, and addresses intricate problems of Muslim identity since then.

-

![]()

Tell us what you think of our Politics, Power & Protest list, and suggest novels about politics we should have chosen.

-

![]()

Review novels on other themes

See all our The Novels That Shaped Our World surveys

Choosing which perspectives to show

In our Novel Perceptions study we have used innovative computer analysis to take a closer look at the language of the 91�ȱ� panel’s selection. Using computer analysis we have identified words which occur significantly more than statistically probable, and noticed differences in the pronouns that our male and female authors favoured.

When we compare nouns referring to family in the women’s novels we find ‘dad’, ‘mum’, ‘sister’, ‘folks’, ‘mother’, ‘aunt’, ‘family’, ‘aunty’, ‘daddy’, and ‘mama’ occurring frequently.

In the novels by men we only find ‘father’ and ‘mammy’. The novels by women writers tend to take a broad view of society, while the focus on family is narrower and more hierarchical in male novels.

Have the unequal opportunities faced by women led them to adopt different strategies in public spaces dominated by men?

Creating a different mood

In the 91�ȱ� novels, the word ‘blood’ occurs 55 times in the women’s writing, but 157 times in the men’s. The prevalence of blood - often associated with violence - is telling. ‘War’ can be found 24 times in the women’s novels and 66 times in the men’s. In the novels written by men, the word ‘war’ was frequently found near the word ‘heroes’. This pattern was absent in the novels by women.

We find an even bigger contrast with the word ‘love’: in the male fiction it occurs 135 times compared with 341 times in the female novels. Even more interestingly, in the novels by women, ‘love’ is combined with ‘unconditional’ whereas in the male fiction it often appears together with ‘abolish’.

The novels by men included more examples of ‘smoke’ and ‘fire’, as well as features of the landscape such as ‘rock’, ‘mountain’, ‘sea’ and ‘forest’, evoking outdoor, public spaces. The novels written by women had more instances of ‘school’ and ‘home’.

Differences such as these not only shape our reading experiences; they may also help us think differently about what power means and who wields it – and how.

Would a different selection of novels tell a different story?

Such findings are intriguing, but are only a starting point. The selection of The Novels That Shaped Our World may be a subjective list, but it’s an interesting experiment that seems to suggest that linguistic analysis can show subtle differences between novels published by authors of different genders.

Our next step is to widen our selection of novels. To do this we need your help. We would like the public to nominate their favourite books about power, politics and protest so we can compare these with choices from literary professionals and academics.

The word ‘blood’ occurs 55 times in the women’s writing, but 157 times in the men’s.

You can take part in the study

Help us by rating one or more of the novels our panel have chosen, and then telling us about which novels we should have included.

The Novel Perceptions project is led by Professor Sebastian Groes at the University of Wolverhampton, and Professor Karina van Dalen-Oskam at the Huygens Institute, The Netherlands.

Calling all readers

You might also like

-

![]()

The Novels That Shaped Our World

Last year, a panel of authors and literary experts chose a hundred novels that changed them. See the full list.

-

![]()

Get personalised reading recommendations

Help us complete the largest ever survey of English novels, and get recommendations for your next great read.

-

![]()

Between the Covers - Our guest's favourite books

Which novels did our guests choose in 91�ȱ� Two's new book club?

-

![]()

Making a protest: Ten political novels to challenge your views

Find out more about the ten novels about Politics, Power and Protest that our panel chose for The Novels That Shaped Our World.