The unlikely origins of Napoleon Bonaparte

“Posterity will do me justice.”

So declared General Bonaparte from his exile on the island of St Helena, after his final capture at the Battle of Waterloo by British forces in 1815.

Beaten, but not broken. Defeated, but defiant.

With a blockbuster film telling his story this autumn, award-winning podcast Real Dictators turns the spotlight on 18th-century France.

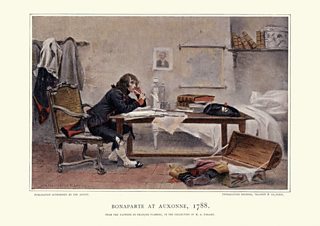

A forensic first episode uncovers how a simple man from a rocky Mediterranean island began his rise to becoming one of the most notorious leaders in world history.

What shaped Napoleon? Read on to find out.

The second son of Corsican rebels Carlo and Letizia, Napoleone di Buonaparte entered the world on 15 August, 1769, a mere year after the French purchased the island from the Genoese government.

Although his family had minor aristocratic roots, life was tough for the Buonapartes on an island where they were forced to cede to their new masters. Young Napoleone detested the French and everything they stood for; as an angry 20-year-old penning that he was born “as the fatherland was dying”.

He served for the army he wanted to overthrow

In order to feed his wife and eight children, Napoleone’s father Carlo set aside his anti-French sentiment to work with the occupiers. In the process, he secured school places for his eldest sons Joseph and Napoleone at prestigious schools on the mainland. At just nine-years-old, Napoleon left home for a military school, where he was bullied.

Princeton professor of history David Bell remarks, “His great ambition until 1793 was to bring Corsica independence from France. It is rather funny therefore to think about him serving in the French army he was hoping to defeat.”

He has a similar backstory to other dictators

School toughened him but, as the aristocratic French teenagers he studied with looked down on him, he retreated into his own company and became a voracious reader. He filled his head with dreams of emulating Hannibal, Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. In the same way as future tyrants Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin, Napoleone was an outsider and did not think of himself as French – not yet. This, says Professor Bell, “gave him an advantage as he could see political manoeuvrings more clearly, and more cynically.”

He cut ties with Corsica after the French Revolution

As the French monarchy fell to revolutionaries in 1789, celebrated rebel – and Napoleone’s idol – Pasquale Paoli, affectionately known as ‘Babbu’ or ‘Daddy’, returned to Corsica in 1790. For the Buonapartes, this was an opportunity to reignite independence.

However, by then, Paoli had spent 20 years enjoying British hospitality, in the process developing a fondness for constitutional monarchy. He threw his lot in with royalists and dismissed the attempts of the Buonapartes to oust their occupiers.

They had to flee Corsica – and the soldier decided to go all in as a French officer. From that point, Napoleon emerged.

He impressed with a statement first victory

After the deposed king Louis XVI was executed in January 1793, a new dictatorial government under Maximilien Robespierre embarked on a spree of violence known as la Terreur (the Terror). European heads of state were alarmed. If it could happen in France, it could happen anywhere.

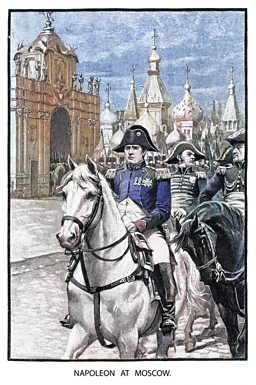

Royalist rebels invited the British to occupy the strategic port of Toulon and in December 1793, Napoleon won his first statement battle. As captain, he chased the British out in a daring mission that won him the spotlight, and a promotion – to brigadier general.

He rose amid the heat of revolution

Andrew Roberts, author of Napoleon the Great, tells the podcast his inexorable rise at just 24 was due to tumultuous domestic conditions.

“One, the revolution got rid of the aristocrats from the army,” he says. “Two, it provided a huge need for officers because war started immediately after it broke out and three, it handed opportunity to Napoleon because he was well connected to the politicians of the day.”

It seems unlikely that without the upheaval and instability prompted by the events of 1789, this “unimpressive student” from military school would have found such breeding ground to prosper in.

He had to fire on his own people

Insurrectionist royalists attacked Paris in October 1795 as 30,000 people massed in central Paris. The job of stamping it out fell to Napoleon who, instead of using cannons on the British, now turned them on the French. He blasted the mob at point-blank range, killing hundreds and suppressing the counter-revolution before it even began. As Roberts puts it, Napoleon “took risks quickly and was decisive. The army became essential to maintain order – and he became indispensable.”

He struggled to impress women

For all Napoleon’s exploits on the battlefield, his conquests in the bedroom were less impressive.

Rejected by a merchant’s daughter, the scrawny, shabbily-dressed general needed help from a political connection to find love. Paul Barras, newly appointed executive leader of the Directory regime, handed over his mistress Marie Josèphe La Pagerie to Napoleon and the military man was besotted.

She, however, was less so, and enjoyed sharing his love-haunted writings with her friends to their great mirth. And yet, the two were good for each other, says Roberts, as she “taught him to behave in high society” and he was her meal ticket to power.

Does history judge him kindly?

Make your own mind up by listening to the full series of Real Dictators – available now on 91热爆 Sounds

More from the 91热爆

-

![]()

Short History Of...

Witness history's most incredible moments and remarkable people.

-

![]()

Being Roman with Mary Beard

Mary Beard uncovers six fascinating stories from the Empire.

-

![]()

You're Dead to Me

Greg Jenner brings together the best names in comedy and history to learn and laugh about the past.

-

![]()

History's Secret Heroes

Helena Bonham Carter shines light on extraordinary stories from World War Two.