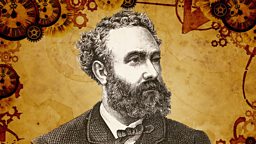

Why Jules Verne is the ultimate steampunk hero

As Radio 4 embarks on a journey with a set of Victorian adventure stories, we examine how the work of 19th-century French novelist Jules Verne feeds into the modern steampunk movement.

What if modern technology existed in the Victorian age? That’s steampunk’s simplified anachronistic premise. Picture the noisy collision of today’s machinery with 19th-century materials and characters.

Steampunk imagines a past that never existed. The term was coined in the late 1980s to describe a science-fiction subgenre of Victorian-set fantasy. It’s since tentacled out into something between a hobby and a movement. Through eccentric, home-crafted period dress and gadgetry, steampunks escape from the here-and-now into the never-was. They look back to an age when science and engineering were greedily stripping the world of secrets.

Nowhere is that age evoked with more vigour than in the adventure novels of 19th-century French novelist Jules Verne. Here’s what makes Verne the godfather of steampunk.

Professors, captains and eccentrics: Verne’s heroes

The steampunk spirit goes deeper than flying goggles and top hats; it’s about the restoration of values including etiquette, connoisseurship and individualism. The figure of the mad professor – a learned eccentric elevated by his expertise and ingenuity – is central.

The steampunk spirit goes deeper than flying goggles and top hats; it鈥檚 about the restoration of values including etiquette, connoisseurship and individualism.

Prof. Otto Lidenbrock, the geologist-adventurer who takes the titular Journey to the Centre of the Earth in Verne’s 1864 novel, is this figure’s archetype. As author Diana Wynne Jones writes in her introduction to the Penguin Classic edition, “Every other mad professor ever since is simply an imitation of this one.”

Engineering genius Nemo, the mysterious submarine captain at the heart of Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), provides another template. Nemo shuns society to live underwater in Victorian splendour. His ship carries a piano, paintings, a library of 12,000 volumes, a priceless collection of marine artefacts and a monogrammed dinner service etched with his Latin motto. A polyglot aesthete who builds his own underwater stun-guns and fights sharks in hand-to-fin combat, Nemo is an original steampunk anti-hero.

Extraordinary voyages: Verne’s expeditions

Neither Lidenbrock nor Nemo – nor the aloof and exact Phileas Fogg of Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days (1873) – exhibit the politeness admired by steampunk culture, but they do embody steampunk’s spirit of discovery and exploration.

Verne’s most famous novels were fantastic travelogues imagining strange modes of locomotion to new horizons. He shot characters into space and out of erupting volcanoes. He took readers to the ocean floor, miles under the Earth’s crust and into orbit around the moon.

Steampunk is doused with that same spirit of pioneering wanderlust. Its followers adopt personas of dirigible captains and international explorers, characters for whom machines have made the planet suddenly conquerable.

Machines, engines and weaponry: Verne’s gadgets

Verne and steampunk share a fascination with technology and scientific apparatus. The same dials, pumps, meters, gears and coils which scatter Verne’s novels also decorate the costumes and accessories steampunks build and wear.

Fanciful as they may have seemed to a 19th-century audience, the vehicles and weapons Verne invented were based on contemporary science. Many, including the electric submarine and solar-powered spacecraft, eventually came to pass (though regrettably, steam-powered mechanical elephants in his novel The Steam House have yet to hit the mainstream!).

Conquering the unknown: Vernian ambition

When a giant sea-monster appears to be terrorising naval vessels in the opening pages of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the novel’s narrator joins an expedition to hunt the creature. He decides that “ridding the world of this monster was [his] veritable vocation and the single aim of [his] life.” The same single-mindedness seizes Prof. Lidenbrock in Journey to the Centre of the Earth when he decodes a message containing directions to the Icelandic volcano where said journey begins. Phileas Fogg typifies the can-do attitude of Verne’s protagonists when he makes the potentially ruinous wager that he can achieve a seemingly impossible feat and tour the world in just 80 days.

The belief that someone possessed of enough science and nerve can do anything is fundamental to Verne’s stories and to steampunk’s individualist culture. Want to reinvent yourself as an airship pilot? Go ahead, says steampunk. Want to build a functioning prosthetic arm from car boot sale finds and a soldering iron? Be our guest!

Refuge in non-conformity: steampunk’s revolt

“The Nautilus is not only a vessel,” says the narrator of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea about Captain Nemo’s submarine. “It must also be a place of refuge for those who, like its commander, have ceased all communication with land.”

Steampunk is also a place of refuge. Unlike Nemo’s crew, its followers’ escape from the rest of the world might be temporary, but a refuge it remains – one inspired by the imagination and spirit of Verne, and writers like him.

Radio 4's To the Ends of the Earth season begins with Jules Verne's classic Journey to the Centre of the Earth which is available to or download free, for a limited time via the iPlayer Radio app. .

-

![]()

Criminologist David Wilson talks to former bank robber Noel "Razor" Smith about his life in crime.

-

![]()

Plays, adaptation and dramatisations with Britain's best actors.

-

![]()

Exceptional readings and dramas from Radio 4.

-

![]()

Readings from modern classics, new works by leading writers and world literature.