The Day When God is Dead

An exploration of grief as the journey without destination, and the hope that can follow…

In a special Radio 4 documentary, The Right Rev James Jones reveals the little-known story of Holy Saturday, the early church’s dark night of the soul

As a Bishop, I’ve accompanied many people in their mourning. Those whose lives have been destroyed by the infected blood scandal; those whose loved one’s lives were shortened at the Gosport War Memorial Hospital; those survivors and the bereaved through the Grenfell Fire.

Margaret Aspinall lost her son James in the Hillsborough Disaster – her dark night of the soul. Through the lives of the Families of the 97 who died in the football disaster, I’ve observed how grief is a journey without destination. Like the grief of those who followed Jesus to the Cross and witnessed his unlawful killing.

Listen to The Day When God Is Dead. Combining theology with powerful human stories, The Rt Rev James Jones tells the story of Holy Saturday and probes the deep psychological truths at its core. There are times in all our lives when we are plunged into grief and doubt the things we hold dear...

I chaired the Panel that uncovered the truth of what happened at Hillsborough and I’ve been a witness to Margaret’s Aspinall’s grieving and her grievances. We’re approaching the 34th Anniversary of Hillsborough. Yet the way Margaret talks about her son James it seems like yesterday. Her grief brings to my mind a statue of another mother, Mary, holding Jesus taken down from the cross. I showed this image – the Pietà – to Margaret…

"That was still Mary's baby. And that saddens me to look at that. I see my own grief and my own child.

It's incomprehensible, to be honest with you, to see her son suffer so much and not have that bitterness in her. What a lovely mother. Mary knows she's met her son again. I'm hoping I'm good enough to meet my son again, I don’t know, but I hope so."

Hillsborough mother Margaret Aspinall reflects on the Piet脿

"It's incomprehensible to see her son suffer so much and not have that bitterness in her"

The day that falls between Good Friday and Easter Sunday is often ignored, as we rush from the darkness of Jesus’ crucifixion to the light of his resurrection. But for Christians, Holy Saturday is an essential step in that journey from despair to hope. It’s a day to experience the doubt and absence Jesus’ disciples felt as he lay cold in the tomb. In this programme, I want to find out what it means – psychologically and spiritually – to have this day when God is dead.

After a traumatic loss there are some who talk about finding closure. But there is never any closure to love. Nor should there be closure. In fact Jesus countered the very idea of closure when he told his followers to remember and to keep on remembering his own death. Rowan Williams, the previous Archbishop of Canterbury, explained the significance of that day, Holy Saturday… was it beginning of the remembering?

"We don't rush towards a happy ending after Good Friday and Easter Sunday doesn't just make us say, 'Oh well, we can forget about Good Friday.' In between there's been this period where you sit with, you digest the level of the loss, the darkness. And well, you find your way through that, waiting through that darkness to whatever it is that opens the doors on Easter Sunday."

To what extent can we say that Holy Saturday was a day when God was dead?

"In some sense, that is literally the case, because the person in whom Christians believe God lived uniquely was on Holy Saturday a dead person. That’s a paradox. It's something which really stretches our imagination, our resources of language, but it also says something about the fact that death is not a place where God is not, death is somewhere that God can contain, inhabit, accompany."

Words fail us to describe great mysteries. We resort to images and paintings, to sculptures, parables and stories to express the unfathomable. Artists have sought to penetrate the mysteries of Holy Saturday by capturing it in canvas and in stone. The day after a death is a bewildering time – you are suspended between your old familiar world and a foreign landscape of unknowns that you begin to navigate. This is the No Man’s Land of Holy Saturday. I went to the National Gallery to meet Dr Siobhan Jolley, their specialist in Art and Religion and talked to her about Holbein’s painting of the Christ "dead and buried".

Here Holbein has produced this incredible wide and very claustrophobic sense of Christ in the tomb.

"I think one of the reasons that it's so striking is precisely that, that we've got this very elongated, very thin body that's already starting to show the signs of decomposition. His face, he's got this greeny-grey pallor to it. And these long, spindly fingers, these incredibly bruised hands and feet, almost of reaching out of this confined space. There can be no doubt for the viewer looking at this that it is a dead body that they're being confronted with."

I asked Siobhan if what we have is not just a dead man, but as some critics have observed, a dead God.

"That’s why this image can be so striking and so resonant. One of the more interesting interpretations of this scene is by an artist called Kehinde Wiley. Kehinde had an exhibition here at the National Gallery but this is from a much earlier series which depicted fallen warriors and prone heroes. We've got a young, very healthy black man and he's not dead. His eyes are open and he's looking out towards the viewer. This is a young man who very clearly should not be in that tomb looking out to the viewer as if to say how am I here? Why am I here? There is a real injustice here, that this is a young man 33 years old who should not be in a tomb, who should not be dead."

In that journey of grief without destination the grave is one of the milestones. Lyn Connolly’s son Paul was murdered – getting out of a taxi one night he was stabbed by a stranger and died. On the path to Paul’s grave Lyn found herself, in Biblical terms, in the "Vale of Tears".

"I could never walk past it. It was one of those things that you think if I ever go past you feel as if, oh, that's not showing love or respect. I used to, I suppose, go just to feel close to Paul, to cherish Paul. But when I went, it was just tears. It was pain. And it was really deep grief and guilt. I remember saying – a lot – 'I'm so sorry, Paul.'

"Thankfully it was just at that time. It was no comfort to me. But God, one day, he interrupted my grief. And this day, when I was there, I just got that Scripture came to mind. Why seek the living among the dead? And it had such a huge impact on me because I thought that's true, he isn't here and that realisation was just such an amazing comfort. I think when somebody dies, you only want to know two things, really: where are they and are they safe? And I could answer both of those and I thought, yeah, I know he's with you, Lord. No one can hurt him anymore. And in those days, I think heaven became more real even than here."

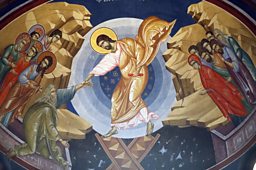

On Holy Saturday, beyond the waiting of the bereaved disciples and beneath the stillness of the tomb there is a parallel drama being acted out. The narrative is told most powerfully in the icons and liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church, as Rowan Williams explains…

"The way in which Eastern Orthodox icons depict the Resurrection, it’s a picture of Christ descending among the dead. When Jesus enters into that realm of the dead, into the underworld, the realm of the forgotten, the long departed, he, as it were, says to them, 'There is a possibility that is a future open for you, which you never dreamed of. And there's a new level of fulfilment into which you can enter.' So the story there of the Resurrection is not simply about something that happens to Jesus, but something that happens to the human race."

The idea of Jesus descending into Hell, to reach out to the faithful dead, entered the Creed only in the early 4th century. But there are hints of it in the New Testament. And it’s depicted in an altarpiece by Giovanni dal Ponte at the National Gallery.

"We have the doors of hell and underneath them are some demons being crushed. So Christ has kicked these doors down, and here we've got John the Baptist, the forerunner, who is first of all guiding Adam and Eve, and then this endless stream of other patriarchs and figures from the Hebrew Bible who are being saved. And actually we've got another really beautiful tiny panel here by Juan de Flandes, and here you can see this sea of heads and it's depicting this saving action is so much more."

The first witnesses to the resurrection were women. At the National Gallery, Siobhan Jolley showed me Titian’s famous picture capturing the moment Mary Magdalen meets the risen Jesus. I've known this painting for many years, this is the first time that I've stood in front of it. This scene is of the Risen Jesus with Mary Magdalen. What I see so strongly in this Noli Me Tangere (Don't touch me), is that he's, as it were, recoiling and yet leaning into her. Almost a paradox.

"It's a very unnatural pose. Jesus is very awkwardly clasping that white garment around him and really pulling himself away from Mary Magdalen. This is a definite 'do not touch me' or 'do not cling to me'.

"And that's why I would always read this as 'don't cling to me' as an instruction not cling to the way things were, but let's think about the way things will be."

Grief is not a static state. It changes people and communities. Many marriages and friendships don’t survive grief. But grief can be as creative as it is destructive of human bonds… if only we can resist that urge to cling to the past.

Lyn Connolly found herself going into prisons with no experience except that of a murdered son’s mother. Her journey of grief led not to closure, but opened up a new world where perpetrators of violent crimes, including murders, met their mothers in her…

"Sometimes we think, God is a God of all comfort, the Bible says. The people who killed Paul have never said sorry, but these people did, and that sort of healed that part of me. And these people, they thought of their victims – and I was like a surrogate victim, and they were like a surrogate offender. It was so powerful being able to talk to them and I just remember looking out and just thinking you're damaged and you know we're all broken here. But there's hope.

"I miss having a son. And these people in prison... well, it's like God's given me hundreds of sons. And I write to lots of them and I hope I say things to them that their mothers would probably want to say. Sometimes they've had absent parents, absent family, but again, it is just I feel like the Lord is making things up to me, by bringing me into this place where all these lads are just hungry for affection and for things that we take for granted in life. That's so powerful. And I tell the men, I say, you know. You all have a story. And you can help other people."

"It is finished." Jesus’ last words from the Cross. They echo throughout Holy Saturday. The end of the Incarnation! Jesus – "a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief". "Crucified, dead and buried." Revealing to us the utter humility of God. It’s the end, but not the end. The focus shifts from Mary, his tearful mother, to Mary who wept for the forgiveness of her sins. In the dawn of the following day she found the empty grave and through her tears thought she saw the Gardener of Gethsemane. It was a gardener she saw, but it was the Gardener of Eden, hoe in hand, with scars and wounds unhealed, promising to journey on beyond the grave and to make all things new…

It is a day in which life is pushing through constantly. And I think of that, that deep mystery of life buried in the darkness of the Earth, pushing towards the light unstoppably. That's the source of our hope.Rowan Williams

Rowan Williams

"It is a day in which life is pushing through constantly. And I think of that, that deep mystery of life buried in the darkness of the Earth, pushing towards the light unstoppably. That's the source of our hope, and that's the presence with which, and in which, we wait on Holy Saturday."

Margaret Aspinall

"I know I'm getting the help from somebody very special. I don’t mean James, I mean God himself. He must be helping give me the strength to carry on. He's let me live my life without my son. To see my children growing up and to see grandchildren born. I've got a lot to thank God for. I know where James is, even though it still hurts me and I do get angry that why didn't you let me have him for more years? Many more years. Why didn't you? But who knows, maybe James had a job to do elsewhere. I don't know. I don't know."

Eastertide on 91热爆 Radio

-

![]()

Easter at King's

Live from King's College Cambridge, Daniel Hyde conducts the 91热爆 Concert Orchestra, Philharmonia Chorus and soloists in Dvorak's Stabat Mater.

-

![]()

Good Friday Meditation

The Wounded Surgeon: The Rev Lore Chumbley, a former hand surgeon, reflects on the healing hands of the Crucified Christ.

-

![]()

Easter: A Matter of Life and Death

Master of the Temple Church, Robin Griffith-Jones, presents an Easter special with music sung especially for the programme by the 18 voices of the Temple Church Choir.

-

![]()

Easter Sunday Worship

A celebration of the Eucharist with the archbishop of Canterbury's Easter Message. Led by the Dean, the Very Rev鈥檇 Dr David Monteith. Live from Canterbury Cathedral.