Who Wrote Shakespeare?

Many people have wondered what William Shakespeare would be doing if he were alive today.

Would he be writing for the stage, or considering that his plays were created as popular mass-entertainment would he instead be working as a scriptwriter for film or television? Are they the modern media which are the closest equivalents to the stage of the Globe Theatre?

Dr Martin Wiggins of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon has examined years of scholarship, on a line by line basis, of the authorship of the known canon of Shakespeare's plays. As he reveals, this analysis makes a present day career for the Bard, perhaps as lead writer in the Writers' Room of a hit TV series like House of Cards or Breaking Bad less crazy than it might at first appear...

-

![]()

Did powerful and independent contemporary women inspire Shakespeare's compelling female characters?

-

![]()

A pioneering partnership produced by the 91�ȱ� and British Council with partners the RSC, Shakespeare's Globe, BFI, Royal Opera House and Hay Festival

In the early 1610s, Sir George Buc, the Crown official responsible for the oversight of the English commercial theatre, acquired a printed copy of an old play called George-a-Greene, the Pinner of Wakefield. As well as being the government’s regulator and censor of drama, he was also an enthusiast, so it irked him that the book didn’t say who the author was. So he asked someone who might know: the longest established playwright still working in the business, William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare told him what sounds like an obvious cock-and-bull story: George-a-Greene was written, he said, by ‘a minister, who acted the Pinner’s part in it himself’. Obviously dissatisfied with that answer, Buc addressed the same question to the veteran actor Edward Juby, and was told, more plausibly, that the author of George-a-Greene was Robert Greene – who happened to have said some scandalously rude things about Shakespeare on his deathbed in 1592, that still stung the greater playwright years afterwards.

The point of the story is that, towards the end of Shakespeare’s professional career, people who were interested in plays wanted to know who had written them. That wasn’t always the case.

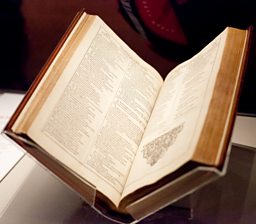

It wasn’t until 1598, with Love’s Labours Lost, that his name appeared on the title page

Shakespeare started writing for the stage in 1591, and selected scripts began to appear in book form three years later, but it wasn’t until 1598, with Love’s Labours Lost, that his name appeared on the title page. The seven Shakespeare plays published before that, including Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, and Richard II, appeared without any attribution, just like that copy of George-a-Greene that irritated Sir George Buc all those years later.

Thereafter, Henry V managed to be printed in 1600 without a by-line, but then ascription became the norm, and booksellers might even invite their customers to buy Thomas, Lord Cromwell ‘written by W. S.’ (actually by Thomas Heywood), or The London Prodigal ‘by William Shakespeare’ (actually by Thomas Dekker), or A Yorkshire Tragedy ‘written by W. Shakespeare’ (actually by Thomas Middleton). Evidently Shakespeare’s name had been recognized as a selling point.

Shakespeare on Tour

Raising the curtain on performances of The Bard’s plays countrywide from the 16th Century to the present day.

Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus was performed at the Rose Theatre in London on Thursday 24 January 1594.

The play which was performed the day before was the lesser known George-a-Greene, the Pinner of Wakefield.

Sir George Buc, Master of the Revels, later acquired a copy of George-a-Greene, the Pinner of Wakefield and tried to establish the name of the author.

Sir George Buc’s copy still survives in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C., complete with the notes from his personal interview with William Shakespeare...

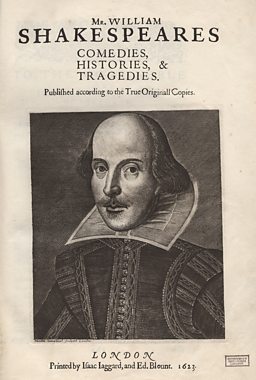

So how do we know exactly what plays he did and didn’t write? Unlike Sir George Buc, we can’t just ask around, but at least we have a secure starting-point in the printed collection of 36 of his Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies that was compiled after his death by his colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell, and published in November 1623: the ‘First Folio’. It isn’t his Complete Works, for he had a hand in at least six more plays that weren’t included:

- King Edward III, printed in 1596 without ascription;

- Pericles, Prince of Tyre, printed in 1609 with his name on the title page but with a garbled, pirated text;

- The Two Noble Kinsmen, a collaboration with John Fletcher printed in 1634 under both authors’ names;

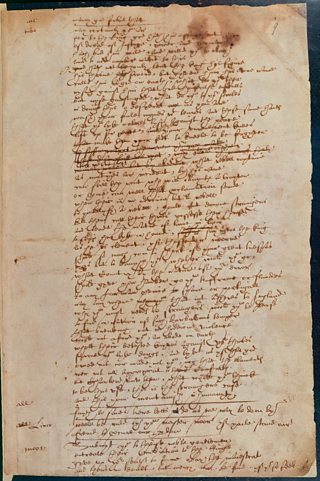

- Sir Thomas More, a chaotic working manuscript now in the British Library, with a page in Shakespeare’s handwriting;

- Cardenio, another collaboration with Fletcher which survives only in an adaptation published in 1728, in which the reviser left much of Fletcher’s work untouched, but sedulously rewrote most of Shakespeare’s;

- Love’s Labours Won, a lost play now known only from mentions in a literary guidebook of 1598 and a bookseller’s catalogue of 1603, and possibly also a cryptic allusion in a later comedy.

Five of those six plays were written in collaboration with other authors. (Of course, we shall never know about the sixth, Love’s Labours Won, unless someone someday discovers a copy.) Could that be why they didn’t make it into the First Folio? Probably not. Because the other difficulty thrown up by the collection is that six of the 36 plays it does include also contain a significant amount of material written by other men.

Putting it in a nutshell, William Shakespeare wrote most of what we now know as ‘Shakespeare’, but not the whole of it.

William Shakespeare wrote most of what we now know as ‘Shakespeare’, but not the whole of it

Again, how do we know? Partly it comes down to how different authors use language. Everybody in the world has their own distinctive ‘voice’: their way with words, their little phrases, the rhythms and structure of their sentences, which collectively might be thought of as their linguistic ’fingerprint’. If you know someone well enough, you will often recognize instinctively when it’s them talking and when it’s somebody else; and this is just as true of professional writers as of ordinary people, even playwrights whose words go into the mouths of many different characters.

Shakespeare or Fletcher?

Can you recognize Shakespeare’s voice when you hear it? Here are two passages from The Two Noble Kinsmen, in which some scenes were written by Shakespeare and some by a younger dramatist, John Fletcher. Both are speeches by the Jailer’s Daughter, who falls for one of her father’s prisoners, helps him to escape, and then goes mad with grief when her love proves to be unrequited.

Both speeches are performed by Danusia Samal, who plays the part in the . But which is Fletcher and which Shakespeare?

Shakespeare's only surviving literary manuscript

Sometimes it may seem obvious when we’re listening to Shakespeare rather than another author.

Here’s Ian McKellen performing a speech from Sir Thomas More, in which the title character quells an anti-immigration riot in London. More begins his speech with the words, 'Friends, masters, countrymen'.

In Julius Caesar, written about eighteen months before Sir Thomas More, Mark Antony begins his address to the Roman mob in almost exactly the same terms: ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen’. But that gives us a problem. More’s ‘Friends, masters, countrymen’ is obviously Shakespearian, but is it a case of Shakespeare recycling his own material, or another writer channelling Shakespeare?

The circumstantial evidence is a little stronger in Edward III, in which the King tries unsuccessfully to seduce the Countess of Salisbury and earns himself the condemnation of her father, the Earl of Warwick, played here by Paul Eddington in the 91�ȱ�’s 1977 radio serial, Vivat Rex:

One line in that speech, ‘Lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds’, also appears in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 94, which was written around the same time as Edward III, but was only published in 1609. It’s a reasonable inference that Shakespeare wrote them both, but is it beyond reasonable doubt?

The problem is that anything writers do deliberately will be easily imitable by others; so to be sure, we have to look at the words they use without really thinking about it.

In Shakespeare’s time, English usage had not yet been standardized, so the small, functional words we need to make ourselves understood could be found in a range of different forms, and different writers had different preferences. Fletcher, for example, was much more likely than Shakespeare to use ye than you, and to use the casual, worn-down ’em rather than them. That doesn’t mean that every time you hear ye or ’em it must be Fletcher and every time you hear you or them it must be Shakespeare: the preference is a statistical tendency across a large run of writing that can be detected by computers more easily than by the impatient human ear.

Computers have also shown us how an individual author will habitually use consecutive strings or three or more commonplace words that are rarely found elsewhere in the same configuration. These are the kinds of things that authors write without knowing it, and that we may perhaps hear and recognize without knowing why, and which help attribution scholars to identify who wrote which bits of which plays.

Want to try testing yourself again?

Here are two more passages from a play Shakespeare wrote in collaboration with Fletcher, this time Henry VIII. In one extract, Cardinal Wolsey, played by Ian McNeice, reflects on his fall from power, while in the other, King Henry VIII (Danny Sapani) hears from the Queen’s lady-in-waiting (Pauline McLynn) the news that he has a new baby daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth I.

Which dramatist wrote which?

(*The answers, to both these Henry VIII clips and the clips from The Two Noble Kinsmen, are at the bottom of the page.)

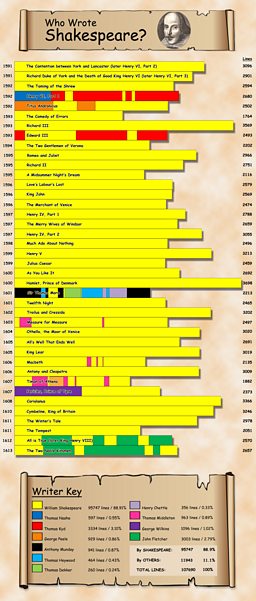

So who wrote ‘Shakespeare’? The results are in: 89% of the canon was by William Shakespeare, and contributions by ten other playwrights account for the other 11%. This chart shows you exactly who wrote which bits of which plays:

At one level all this is not very important: no matter who wrote what, each play is a complete entity designed to be seen and enjoyed as a whole, and nobody in their right mind would sift out the Shakespearean material and throw the rest away. But the chart does help us to understand more about the circumstances in which the plays first came into being.

This production-line process made it possible for plays to be written rapidly

The usual mode of dramatic collaboration in Shakespeare’s time began with somebody (not always the eventual author of the play) planning out how a story would break down into scenes. Groups of scenes were then assigned to different authors, who wrote them separately and concurrently, not necessarily in systematic communication with one another. (When writing The Two Noble Kinsmen, Shakespeare and Fletcher certainly never spoke the name of the character Pirithous to one another, with the result that Shakespeare writes it as having three syllables and Fletcher as four.)

This production-line process made it possible for plays to be written rapidly, which was sometimes necessary to feed a demanding market (and for authors to feed themselves and their families). Evidently Shakespeare was not always the senior partner in this, something easiest to understand in the case of Edward III, written at the lowest point of his professional career, after his original acting company had gone bankrupt and before he had found secure, long-term employment with another.

But some of the collaborations seem to have operated differently. Sometimes, as with Titus Andronicus and Pericles, Prince of Tyre, Shakespeare took over plays that had been planned and started by other writers, and made them his own. Sometimes he adapted a play that was already finished: what we now know as Henry VI, Part 1 was written by Thomas Nashe and Thomas Kyd for a rival company as a standalone play to cash in on the success of Shakespeare’s two-parter about the same reign (originally entitled The Contention between York and Lancaster, and now known as Parts 2 and 3); it was later acquired by Shakespeare’s company, whereupon he turned all three plays into a serial and wrote three new scenes for Part 1. And sometimes his own plays were likewise adapted: the non-Shakespearian material in Measure for Measure and Macbeth was added after his death by Thomas Middleton, and these were the only versions available when the First Folio was compiled in the early 1620s.

...something akin to a head writer or script editor in modern television

There are hints, too, that Shakespeare may have worked for his company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, not only as actor and principal playwright but also as something akin to a head writer or script editor in modern television. Perhaps not coincidentally, most traces of this activity come during a period when his own output of solo-written plays had fallen to one per year. This best explains his intermittent interventions in Sir Thomas More, and he may also have contributed to Ben Jonson’s Roman tragedy, Sejanus (1603), written at the same time as Measure for Measure; Jonson later acknowledged that there had been a second author – whom he said he respected but did not name – but carefully revised out the man’s work before publishing the play in 1605.

Since Sir Thomas More ran into serious censorship difficulties and may never have been performed, and since Sejanus was a disastrous flop, booed off the stage at its first public performance, it is possible that literary management may have turned out not to be Shakespeare’s forte. (His solo-written output went back up again after 1604.) And indeed, the chart shows that, from the very start of his career, he seems to have preferred to write alone.

But like almost everyone who is human, and professional, he didn’t always get to work the way he liked.

By Dr Martin Wiggins

Martin Wiggins is the Senior Scholar of The Shakespeare Institute, Stratford-upon-Avon, and author of Shakespeare and the Drama of His Time (2000), Drama and the Transfer of Power in Renaissance England, and the ten-volume British Drama, 1533-1642: A Catalogue (2012-18)

Shakespeare or Fletcher? Answers

*The first clip from The Two Noble Kinsmen "He has mistook the brake I meant" is by Shakespeare, the second "I am very cold" is by Fletcher.

The first clip from Henry VIII "Farewell to the little good you bear me" is by Fletcher, the second "Who's there, who's there I say" is by Shakespeare.

More on Shakespeare...

-

![]()

A Midsummer Night’s Dream meets Fight Club in Shakespeare and Fletcher’s rarely performed tragicomedy at the Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon until February 2017

-

![]()

Experience an incredible commemoration of the Bard's 400th death anniversary with videos feauring David Tennant, Ian McKellan, Adrian Lester and more

-

![]()

Watch some of the most memorable Shakespeare speeches, as chosen by the RSC, featuring Peggy Ashcroft, Patrick Stewart, Vanessa Redgrave and more

-

![]()

From the Bard's influence on pop music to his face appearing on a £20 banknote, discover more unorthodox and unusual tales of Shakespeare from past to present