Have scientists found an exomoon outside our solar system?

- Published

- comments

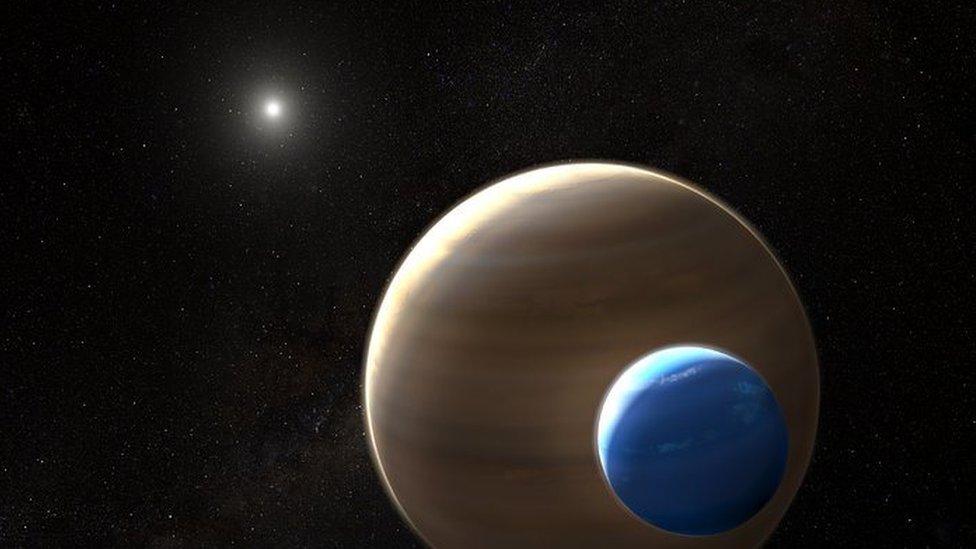

This artist's impression depicts the possible exomoon Kepler-1625b-i, the planet it is orbiting and the star in the centre of the star system

The giant ball of rock hanging in the night sky has long fascinated astronomers and space scientists.

But how many other moons are there that we don't know about?

Astronomers say they have found the first significant evidence for a moon outside our own solar system - an exomoon.

They say data from the Nasa and the European Space Agency's Hubble Space Telescope, as well as older data from the Kepler Space Telescope, indicate it's roughly the size of planet Neptune.

The new results are presented in the journal Science Advances.

On Earth we have just one moon, and neither Mercury and Venus have any.

But some of the other planets in our solar system, have dozens!

Mars has two moons.

Saturn has 53 that have been named, but there are also 9 moons awaiting confirmation.

Uranus has 27 moons that we know of.

Neptune has 13 named moons and one awaiting confirmation.

Jupiter has 79 known moons.

Scientists have long been searching for exoplanets - planets outside our solar system - getting their first results around 30 years ago.

While astronomers now find these planets on a regular basis, they hadn't found any moons orbiting exoplanets.

In 2017, Nasa's Kepler Space Telescope detected hints of an exomoon orbiting the planet Kepler-1625b.

Now, two scientists from Columbia University have studied this planet and a star - more than 8,000 lightyears away - in more detail.

A lightyear is the distance light can travel in a year, and it's a long, long way - one lightyear is roughly 6 trillion miles!

They say the new observations with the Hubble Telescope show compelling evidence for a large exomoon orbiting the planet.

This possible moon is unusual because of its large size.

If this moon is indeed as big as the planet Neptune, it would be much bigger than any moon in our own solar system.

What could the team see through the Hubble Telescope?

To find evidence for the existence of the exomoon, they closely watched the planet before and during its movement in front of its parent star.

They detected a dip in brightness of the starlight during the crossing, and then a second dip about 3.5 hours later.

This would be consistent with the effect of a moon following the planet.

In addition to this second dip, Hubble provided supporting evidence for the exomoon by detecting the planet's movement more than an hour earlier than predicted.

The change could also have been caused by the gravitational pull of a second planet in the system, but the Kepler Space Telescope found no evidence to suggest there are any others.

However further observations will still be needed to fully confirm the existence of the new exomoon, but scientists are hopeful.

"If confirmed, Kepler-1625b-i [the new exomoon] will certainly provide an interesting puzzle for theorists to solve," said David Kipping, who was also involved in the study.

Study leader Alex Teachey said he sees it as "an exciting reminder of how little we really know about distant planetary systems".

- Published18 September 2018

- Published22 August 2018

- Published28 July 2018

- Published8 December 2018