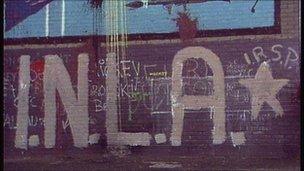

Who are the INLA?

- Published

The INLA has been on ceasefire since 1998

The Irish National Liberation Army was a familiar name on news bulletins throughout the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

A much smaller group than the IRA, it retained a capacity for ruthless killing and was behind some of the most high-profile murders of the period.

The republican paramilitary group is believed to have been responsible for more than 120 murders from its formation in 1975 until its ceasefire in 1998.

Despite its declared ceasefire, the INLA is still thought to have been involved in a number of murders since then.

In February 2009, the INLA claimed responsibility for the murder of a drug dealer in Londonderry.

The group has regularly indulged in bouts of bloody infighting.

Formed in 1975, many of its early recruits were thought to have come from the Official IRA which had called a ceasefire three years earlier.

It came to world prominence in 1979 with the murder of Conservative Northern Ireland spokesman Airey Neave by leaving a bomb under his car in the House of Commons car park.

In December, it was behind one of Northern Ireland's worst atrocities when it killed 17 people in a bomb attack on the Droppin' Well pub in Ballykelly, County Londonderry.

When other paramilitaries began declaring ceasefires in 1994, the INLA did not follow suit until four years later.

In December 1997, Loyalist Volunteer Force leader Billy Wright was shot dead inside the Maze prison by the INLA.

Three members of the INLA died in the jail while on hunger strike in the 1980s.

The INLA murdered Airey Neave in a car bomb outside the Commons

In February 2010, the INLA said it had decommissioned its weapons.

The INLA was believed to have a small arsenal and several dozen active members.

It was thought to hold a small stock of rifles, hand guns and, possibly, grenades and a small amount of commercial explosives dating from the mid-1990s.

In 2009, the Independent Monitoring Commission said its members remained deeply involved in serious crime, with extortion being its main form of income.

INLA members were targeting individuals and exploiting tensions at sectarian interfaces in the recent past, the commission said.

In its report in 2010, it said it "had no reason to change the view we had expressed before that the organisation remained capable of criminal violence".