Liberia Ebola doctor: 'We're going to win very soon'

- Published

Doctor Mosoka Fallah says Liberia defied predictions that 500,000 people would die

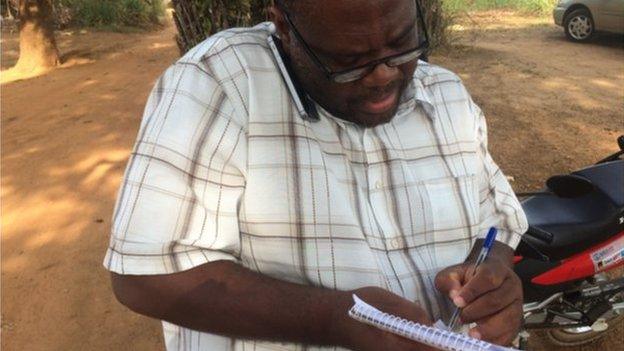

Doctor Mosoka Fallah - a stout, gruff, profoundly earnest man - stood outside a small house on the outskirts of Monrovia in Liberia wondering if this is where it would all end.

"This is the last stretch, the last mile. There's a lot of pressure on us. If they all go for 21 days without symptoms then that could be the end of Ebola," said the 44-year-old Harvard-trained doctor, watching his colleagues take the temperatures of a dozen women and children gathered on the porch.

The Yardolo family are one of the very last "clusters" of potential Ebola cases being monitored by Liberian health authorities in a country that seems to on the verge of eradicating the virus.

Ebola killed more than 4,000 people in this west African nation - the highest figure of the outbreak. But there have been no confirmed new cases in Liberia for a week.

Deputy Minister of Health Tolbert Nyenswah: "It is not over until it is over"

In New Community, a small village north of Monrovia, the virus killed three Yardolo siblings and their mother, Beatrice, is now being cared for at a Chinese-run Ebola Treatment Unit in the city. She is one of only two current Ebola patients nationwide.

"We are pitiful. I'm the one that lost my three children. We have fear and worry," said Beatrice's elderly husband, Steve.

Large-scale trials of two experimental vaccines against Ebola have taken place in Liberia

But 11 days into their quarantine, the surviving family insisted they were all feeling well. I asked Steve Yardolo if he thought this Ebola outbreak might end here. "It's our prayer," he replied.

Dr Fallah - who wears many hats as an unpaid advisor to the Health Ministry, an employee of the international charity ACF, and a community liaison expert - took notes, and promised to bring more food and extra mattresses for the family to help them through the quarantine period.

"It's emotional. It's tough. You can only do this job if you are empathetic. I try my best to understand the pain people are going through," he said.

"In the early months we delayed the [Ebola] response and some of the emails I sent then were full of desperation. But I think the country has risen to the challenge. We've defied the predictions that said half a million [people would die]. We have managed, as Liberians and with our international partners, to achieve nothing less than a miracle.

"I think we're going to win very soon," said Dr Fallah.

Ebola has killed more than 4,000 people in the small west African nation

But that confidence is tempered by a residual anxiety, and by the knowledge that Liberia cannot afford complacency in these final stages of the fight against Ebola. The nation's borders have been reopened, and as of now Guinea and Sierra Leone are still struggling to contain the virus.

And then came the bad news.

As we stood outside the Yardolos' house, one of the many community volunteers rang Dr Fallah to warn him about a woman, who had just been discovered showing Ebola symptoms in a neighbourhood about 10 minutes away by car.

We found a 49-year-old woman lying on a bench outside a small local clinic. She was covered in blood and seemed barely conscious. A relative had brought her here.

It turned out she was one of the Yardolos' neighbours who appeared to have been hiding her illness for several days.

"We've got a suspected case. Temperature is high," said Dr Fallah, juggling two telephones as he called for an ambulance.

"It should be very worrying. If it comes out positive it's very worrying for us. Another 21 days [of quarantine]," he said.

But a day later, I called Dr Fallah on the phone. He sounded elated.

"The test just came back. Negative. The same with one other suspected case of someone who crossed the border from Sierra Leone. So that's nine days now with no Ebola in Liberia," he said.