Laying a global cattle killer to rest

- Published

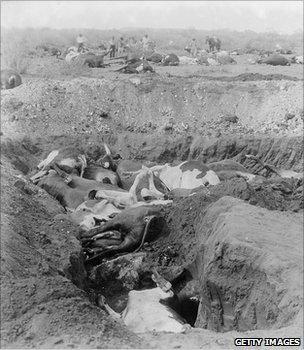

Rinderpest was responsible for killing hundreds of millions of cattle around the globe

After centuries during which it wiped out hundreds of millions of cattle around the world, scientists are preparing to declare rinderpest - otherwise known as cattle plague - formally eradicated.

Untreated, it can kill infected animals within days, wiping out entire herds.

It leaves a trail of economic devastation in its wake.

It is even suggested that the disease may have contributed to the downfall of the Roman empire in 4th Century Europe.

Rinderpest infection generally follows five stages: incubation, fever, lesions and excess mucus, diarrhoea, and death (although a small percentage do recover).

While waves of the disease, over history, regularly devastated buffalo and cattle herds in Asia and Europe, animals elsewhere were spared the horrors of the disease until 1887 when it was introduced by accident into the Horn of Africa.

In 1994, the Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme (Grep) was launched.

Headed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Grep initially focused on establishing the geographical distribution and epidemiology of the disease.

Later, it promoted actions to contain rinderpest within infected ecosystems, and to eliminate reservoirs of infection.

Once experts were satisfied that the virus had been eliminated from a region, surveillance schemes were put in place to ensure it did not return.

Although one of the last places to be infected, East Africa was also one of the last places to become disease-free.

Dr Dickens Chibeu, a Kenyan veterinary epidemiologist, played a central role in freeing the region from rinderpest's grip.

"I have spent the past 30 years of my life fighting for the eradication of rinderpest," he told the Earth Reporters programme.

"A lot of people don't know, but the truth of the matter is that livestock contributes about 30% of the agricultural GDP in Africa, and that is a very high contribution to the national economies."

'Wildfire' of death

Recalling how quickly the disease could spread, Dr Juan Lubroth, chief vet for the FAO, said: "It spreads like wildfire in animals that have no protection, so in a herd of 100 animals, you could lose them all with 10 days."

Maasai pastoralist herdsmen did not think there would ever be an end to the disease, and feared it would destroy their way of life.

However, thanks to the development of the "Plowright vaccine" in the 1950s and later advances in treatments that remained stable in the extreme heat of central Africa, alongside effective control and immunisation programmes, huge steps were made.

But it took a second African pandemic in the late 80s to bring together the world's animal health leaders at a summit in Rome, where a global plan was finally developed to eradicate rinderpest.

The eradication of rinderpest ensures that cultures like Kenyan pastorialists can survive in the future

In November 2009, experts were confident enough that the eradication programme was a success that they could describe the disease as on its "deathbed".

According to the FAO, the rinderpest footprint extended from Scandinavia to the Cape of Good Hope at its height in the 1920s, and from the Atlantic shore of Africa to the Philippine archipelago, with one outbreak reported in Brazil and another in Australia.

Now, experts are preparing to formally declare the global eradication of the cattle plague on 28 June 2011.

"I don't think the green revolution would have happened without the rinderpest vaccine," said Dr Lubroth.

The reason? "Because those animals would not have been able to plough soil or take crops to the market," he explained.

"So I think a lot of people, whether they know it or not, should be grateful."

The Earth Reporters' programme Beating Plague, co-produced by Television Environment (TVE) and the Open University,

- Published14 October 2010

- Published11 May 2011