Liz Hooper never meant to fall in love with two haemophiliacs, any more than she ever intended to be widowed twice. But fall in love with them is what she did, one after the other. And now they are gone, she says, her heart overflows for both men equally.

Sometimes Liz wonders what the chances must have been. A million to one? More?

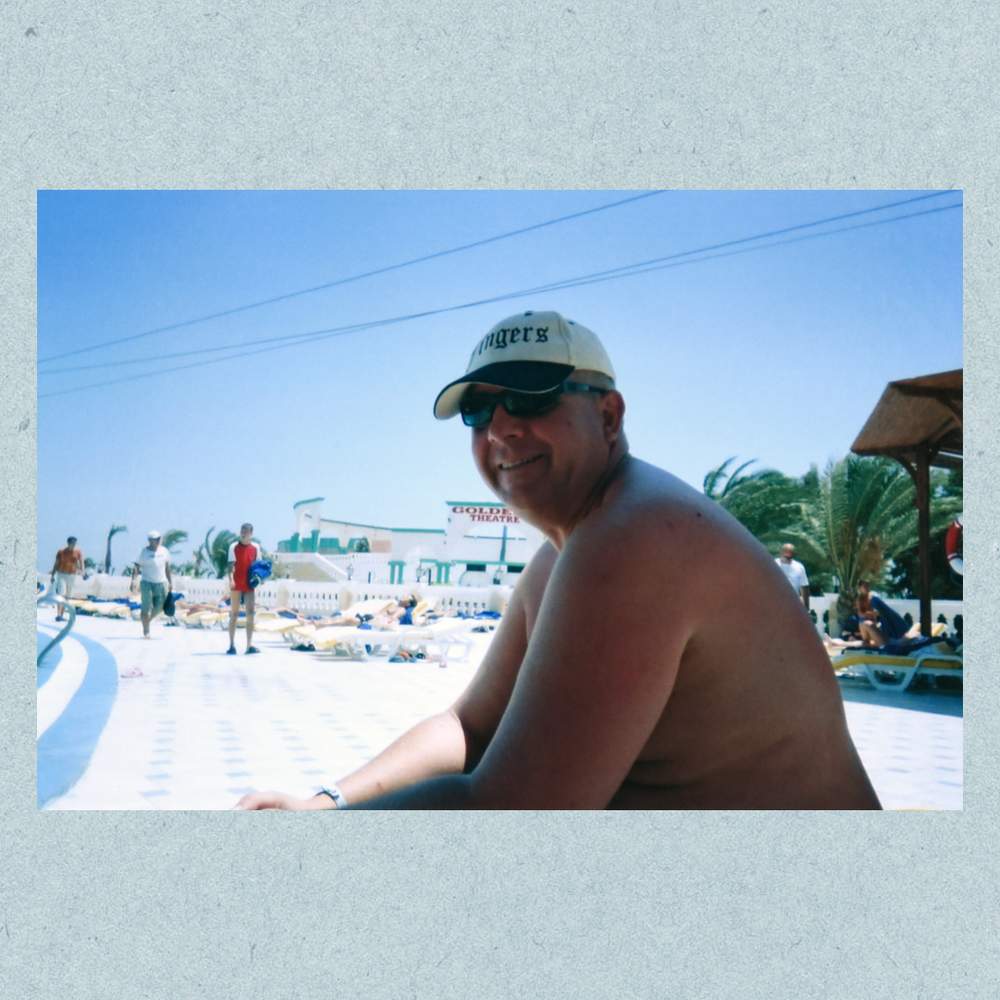

They were such wildly different characters. Jeremy was loud, gregarious, an extrovert - at 6ft and 17 stone, as large a character as he was a physical presence. Paul was his opposite, slightly built, quiet and dry-witted, a gentle man as well as a gentleman.

And what she felt for each of them was singular, unique. Jeremy was her first love, she says, and Paul was her soulmate.

But probabilities aren’t something Liz dwells upon much, barely six months after Paul’s death and almost a decade after Jeremy’s. It's still too painful to contemplate.

What united Jeremy and Paul, as well as their love for Liz and her love for them, was the scandal that killed both men. It's been called the biggest in the history of the National Health Service, and campaigners say it has resulted in the deaths of at least 2,883 British haemophiliacs - though no-one has yet been held accountable.

During treatment for haemophilia, Jeremy and Paul were given contaminated blood products, and they died horribly as a result.

If Liz hadn’t lost Jeremy, she wouldn’t have met Paul. And that’s a bittersweet pill for her to take, she says, as she sits in her living room and recalls them both. “Because I’d wish neither of them dead, but I wouldn't want my life without either of them in it.”

In 1978, when Liz was 13, a special assembly was called for the third year at Kineton High School in rural Warwickshire. The headmaster stood up and announced that a new pupil would soon be joining them and that he had a disease that meant his blood didn’t clot - so no-one was to pick on him and no-one was to fight with him. Liz - then Liz Byng - was intrigued about this boy who was special enough to warrant his own assembly.

Soon afterwards, Jeremy Foyle arrived at the school gates. He was far from the delicate child the headmaster’s warning might have implied. Short, plump and sporting a pudding-bowl haircut, Jeremy was a Chelsea supporter with a London accent - a Jack-the-lad type, Liz recalls, prone to settling arguments with his fists (he was outraged when he learned about the assembly).

Because he arrived mid-way through the school year, he was slotted into whichever classes had space for him, and one of these was, improbably, Liz’s needlework class. Her first impression was that he was, as she puts it, an obnoxious little git.

Jeremy was born on 17 April 1965 in Sutton, on the border between Surrey and south-west London, with severe haemophilia B. The diagnosis arrived relatively late, at the age of nine, after a series of bleeds left him on a plasma drip with both legs in traction. His parents moved to Kineton so he could be closer to the specialist haematology unit at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford, about an hour's drive away.

Despite the severity of his condition, Jeremy went out of his way to disregard the advice of his doctors. When they warned him that getting into playground fights wasn’t good for him, he went out and joined a boxing club. As he grew older, he made a point of turning up to hospital appointments on a motorbike.

From across their needlework class, Jeremy would pass Liz notes asking her to the village disco. Liz wasn't interested. They moved in different circles. Liz was a country girl who liked riding horses. Jeremy became a punk, spiking up his hair with egg whites, going to gigs and drinking too much. After their O-levels, Liz stayed on at school while Jeremy dropped out. “I didn’t see him, other than just around the village, looking like a pillock with his punk hair,” she recalls.

Matthew was infected with HIV at the age of eight.

Read his story here:

In 1982, when Liz was 16, she went to a school end-of-year party in the village hall. Jeremy gatecrashed, and when she spotted him at the door Liz was astonished at how he’d changed. He’d shot up in height. The spiky haircut and the puppy fat had gone. He was dressed like the singer of some post-punk band: black Doc Marten boots, narrow black jeans, a grey shirt and a vintage German military jacket. “He’d become a proper man,” says Liz. In an instant she realised she had fallen headlong in love with him. “I was just totally besotted. And it was mutual because he made a beeline for me.”

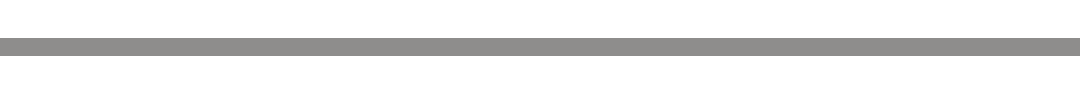

Jeremy stayed by Liz’s side all night. When it was time to leave, he gave her his packet of John Player Special Silver with a handful of cigarettes inside. Liz would hold on to it for years. Then he told her to listen to the song that was playing. It was Only You by Yazoo, and five years later it would be the first dance at their wedding.

After the disco, Liz wrote in her diary: “JEZ LUVS LIZ LUVS JEZ,” and drew a heart around it. They were now a couple, and inseparable.

Jeremy began proving he was more than a rebellious school dropout. After landing a job behind the counter of a builders' merchant, he discovered he had a talent for making sales. “He could sell a fridge to an Eskimo,” says Liz. He rose from the counter to a series of roles as a sales rep and, eventually, as a company sales and marketing director. “He was very driven,” she says. It seemed to her that he had to prove to the world he could achieve things in spite of his illness. “I think being a haemophiliac made him more motivated.”

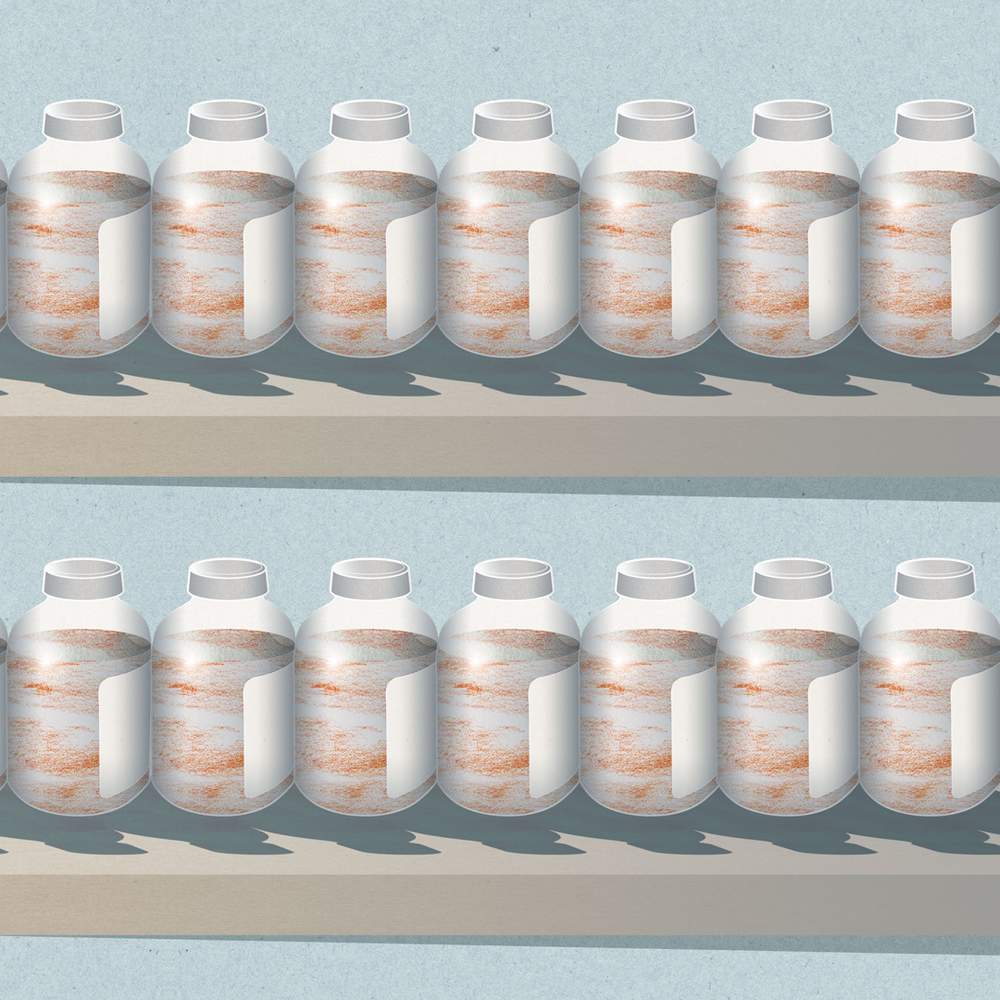

Over time, Jeremy’s drive brought material rewards: a detached home, fast cars in the driveway - at one stage, a Lotus Europa for him, an Escort XR3 for her - and holidays to New York, Las Vegas and Egypt. They had a wide circle of friends, and Jeremy would hold court at barbecues and parties. “If you were in a crowded room, you always knew Jeremy was there,” Liz says. “He was always the life and soul of the party.”

But there was another side to Jeremy that he mostly managed to keep hidden from his friends and co-workers. His bleeds left him in great pain and restricted his mobility - his blood would fill the cavities of his leg joints, making movement extremely uncomfortable.

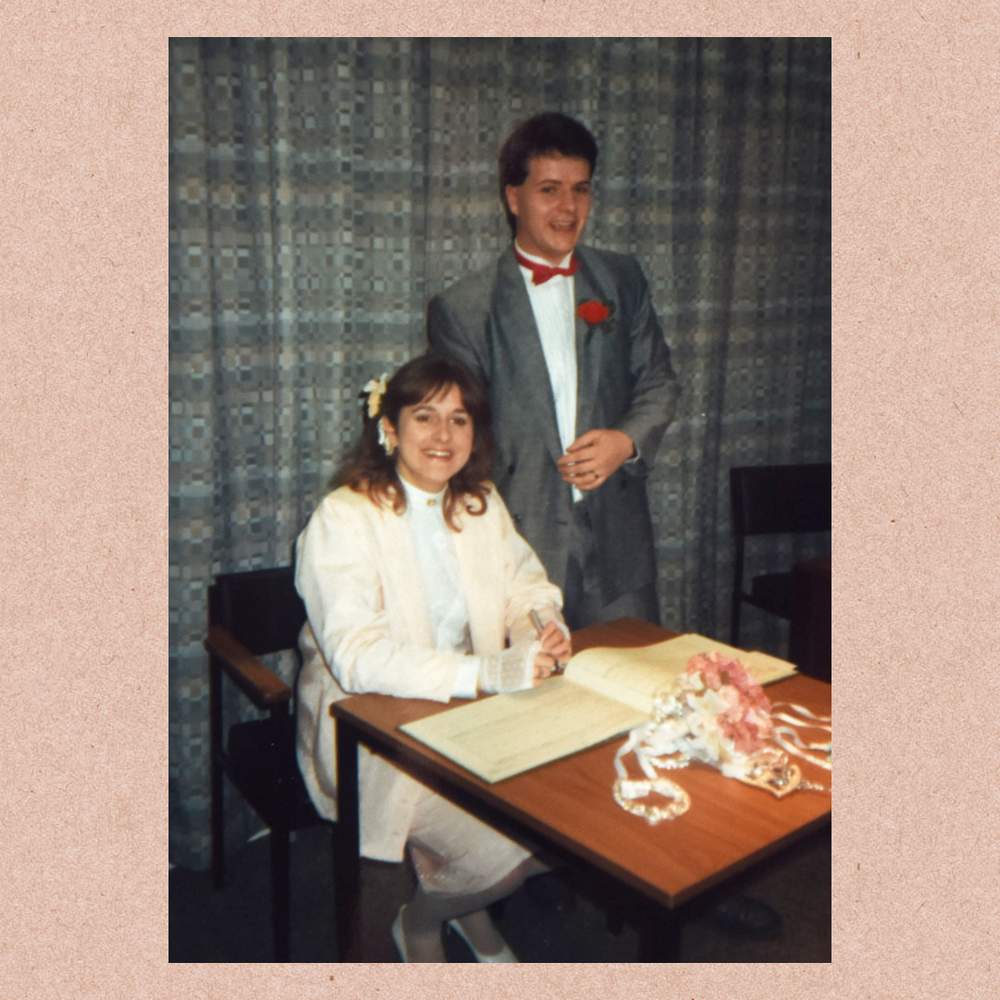

In the 1970s and 80s, a new treatment for haemophiliacs was hailed as a wonder drug. Those with the condition (mostly men) were given injections of proteins called factor concentrates - usually Factor VIII or, in Jeremy’s case, Factor IX - that helped clot their blood. They were made from donated blood plasma, and demand was so high that the NHS began importing them from abroad, including the US.

If Jeremy had a particularly bad bleed, he’d need to use two large syringes to apply the Factor IX, and Liz would help change them over. “It wasn’t just a case of him being this lovely, gregarious, vibrant person. I also knew the fragile person that other people didn’t see. I've sat with him when he cried because he was in so much pain from a bleed.”

Occasionally there would be reports on the evening news about a scandal involving the blood of haemophiliacs being contaminated with infectious diseases. But generally Jeremy felt fine and mostly didn't pay his condition much notice. “He was living a normal life, a happy normal life, he was doing what he wanted, when he wanted. He didn’t want to know anything else,” says Liz. In 1993, the couple’s son, Lewis, was born.

And then one day, three years later, Jeremy answered a phone call from the hospital. He needed to come in, and could his wife accompany him?

The doctor had bad news. Jeremy had a disease called hepatitis C. At some stage he’d been given Factor IX contaminated with the virus.

The problem was the imported factor concentrates. Many of the US donors came from the fringes of society - prison inmates, prostitutes and drug addicts - and were often paid for donating their blood.

The products were made in huge vats from the plasma of tens of thousands of people. Just one donation infected with a virus would be enough to contaminate the whole batch.

As early as 1974, warnings had been raised about the safety of Factors VIII and IX and in 1975 the Health Secretary David Owen told Parliament that the UK aimed to be self-sufficient in blood products within two to three years. It wasn't.

Eight years later, as the Aids crisis unfolded, US blood products were still coming in. The Department of Health received expert advice that they should be withdrawn, but this was not heeded until 1986 - a further three years later. It wasn’t only haemophiliacs who were affected – it is feared that tens of thousands of non-haemophiliacs may have been infected through blood transfusions, too.

It turned out Jeremy had been infected 10 years earlier, and he was livid. “Oh, he was fuming,” says Liz. “The language was foul.” Above all, he was furious because he feared he had passed the virus on to Liz and Lewis. There was an anxious wait before his wife's test results came back negative, which meant his son was in the clear too.

Hepatitis C primarily attacks the liver. It wasn't unusual that Jeremy hadn’t noticed anything was wrong - the disease doesn’t have any noticeable symptoms until the organ is seriously damaged. It can then lead to cirrhosis - scarring - of the liver tissue, and ultimately to liver failure and cancer.

Jeremy attempted to carry on as normal, but when he began to feel tired and lethargic he was offered experimental treatments that it was hoped would kill the virus - ribaviron tablets and injections of interferon. “He was on that for six months and it was the most horrific thing,” says Liz. The drugs made him nauseous, he was unable to sleep and he became aggressive and short-tempered.

“It was probably the closest he and I ever came to being divorced,” says Liz. Each evening he would come home from work and shut himself away from his son and his wife. Liz took it personally, but later, after coming off the drugs, he explained that he hadn’t wanted to inflict his mood swings on them. “He was in such a dark place,” Liz says.

After the six-month course of treatment was finished, Jeremy was tested for the virus, and the drugs hadn’t shifted it. “It was six months of total hell for no reason,” says Liz. Jeremy couldn’t face going back on the medication again. He preferred to live with the risk of liver failure rather than put his family through that a second time.

So he resolved to struggle on and his and Liz’s relationship returned to normal. He was still feeling tired, but he never knew to what extent this was simply down to the pressures of a stressful job. Over time he began feeling stomach pains, but an endoscopy didn’t reveal anything untoward.

He and Liz both knew the risks, and while both were dimly aware that haemophiliacs infected during the 1980s were dropping dead, neither was fully aware of the scale of the problem. “He was scared, but his way of dealing with it was just to be flippant about it,” says Liz. “He always said: ‘Well, you know, I don’t want to make old bones.’”

On 7 December 2008, the family sat down to breakfast as normal. Lewis, now 15, caught his bus to school. Liz went to the insurance company office where she worked part-time handling claims.

Not long before lunchtime, she was in a meeting when a colleague knocked on the door. The mobile phone she had left on her desk was going off. It was Jeremy. “Please can you come home?” he asked. “I’m really not very well.”

Liz raced back to the house and called out Jeremy's name as she stepped through the front door. No-one answered. She went upstairs and opened the bathroom door. “It was absolutely horrific,” she says. There was bright red blood everywhere.

Then she went to the bedroom. Jeremy was lying on the bed, ashen-faced. The colour had drained from his lips. Barely conscious, he told Liz he’d been vomiting blood.

She rang an ambulance. Paramedics arrived to take him to hospital. He was booked in for an endoscopy to see what was wrong. The next morning, before he went in for the examination, Jeremy told Liz: “Right, I’m going to get this done and then I’m going home and I want to have a hot bath and a big cup of tea with sugar.” He didn’t normally take sugar, only on special occasions, as a treat.

Those were the last words he ever said to Liz.

The endoscope was put down his throat, but it didn’t get very far before an internal bleed erupted. He then had a cardiac arrest. The medical staff resuscitated him and rushed him into surgery.

A doctor summoned Liz to tell her what had happened. “I knew from his expression what he was going to say,” she recalls. There was nothing they could do. “I still feel ashamed of myself,” Liz says. “I remember getting on the floor in front of the doctor. I held my arms out and I said to him: ‘Take my blood because if you take my blood, he’ll have it.’” The doctor told her it was too late for that.

The doctor asked if she wanted to see Jeremy. She did, but she would later deeply regret setting foot inside the operating theatre. There was blood everywhere. “It was coming out of his mouth and out of his nose and even the corners of his eyes. His body was just rejecting everything.” She couldn’t stay with him. “It’s a memory that I’ve got etched in my mind and it was just like something from a horror film.”

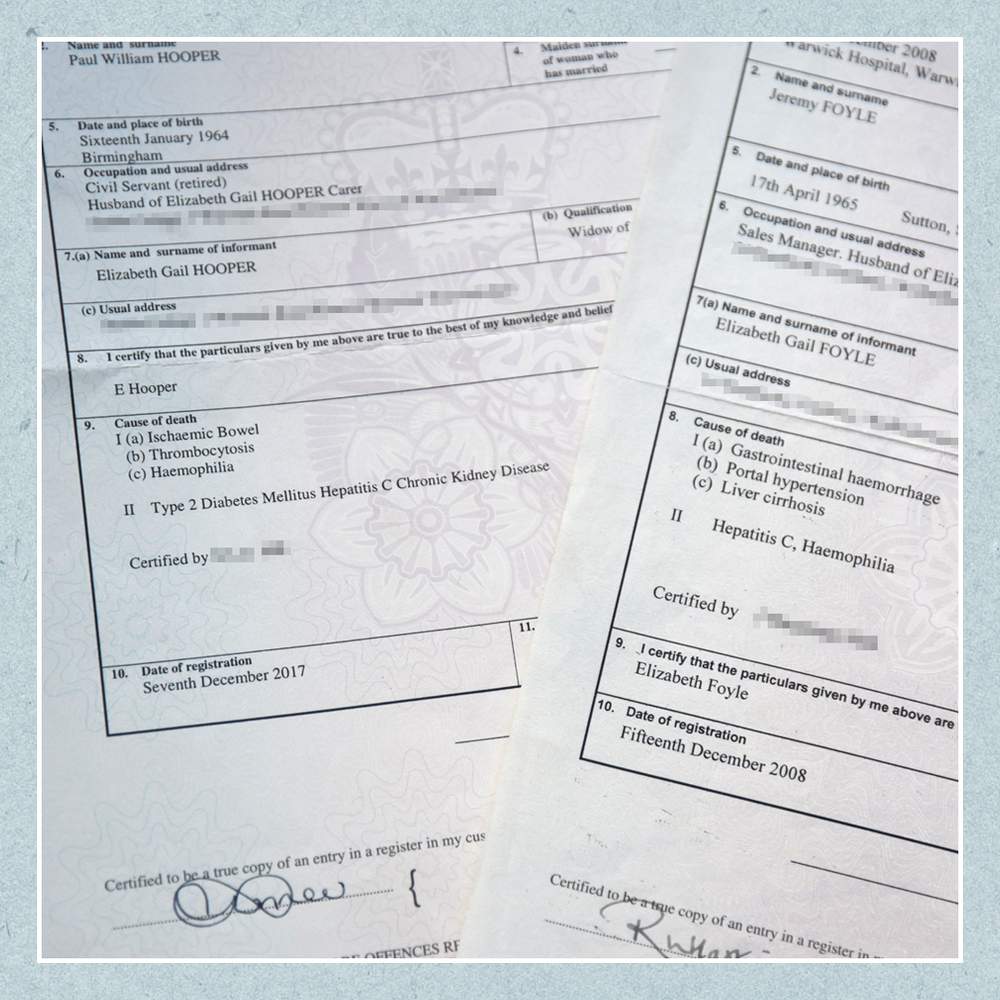

Just before midnight, Liz received a call telling her that Jeremy had died. He was 43 years old. Liz had had no idea that Jeremy, who was never a big drinker, had developed cirrhosis of the liver. On his death certificate, hepatitis C was listed as a cause.

“We just assumed that because of him being a haemophiliac he’d bled to death,” Liz says. But the doctors told her it wasn't the haemophilia that ultimately did for him. Because his liver was so badly scarred, it had become harder for his body to move blood through it. So it had opened up a new vessel to transport the blood - but this “wasn’t up to the job” and ruptured. “It was the hepatitis C. The total cause of his death was hepatitis C.”

Before she could mourn Jeremy, before she could face up to the loss of the man she had loved for 26 years and confront his horrific death, Liz had to go into survival mode.

She didn’t know where to begin. Jeremy had always looked after their finances. He had been on a good wage, and her part-time salary wasn’t enough to cover the mortgage. Despite the scale of the contaminated blood scandal, there was very little in the way of compensation. She was eligible for £25,000 from the Skipton Fund, set up to make payments to people infected with hepatitis C through NHS blood products. But this was a drop in the ocean.

She sold the house. Lewis, still only 15, went through the legal paperwork with her - and found a smaller place to live. One night, not long after she and Lewis had settled in, she sat down to dinner and lifted a fork of spaghetti Bolognese. Before it reached her face, a force hit her, as though someone had punched her in the stomach. “I just went to pieces,” she says. “I cried and cried and cried and cried and I couldn't talk.”

The grief was like nothing Liz had ever experienced. It manifested in her as a searing physical pain, like burning coals in her stomach and hot rods poking into every part of her body. “I had a total and utter catastrophic breakdown,” she says. “I couldn't speak to anybody, I didn’t want people to talk to me, I didn’t want to open my mouth. I just wanted to sit in a corner with a duvet over my head. That was a very, very dark time for me.” It hurt even to make decisions, even whether or not she wanted Marmite on her toast.

“He’d been my life,” she says.

“He was my everything. He was my first love, and it was an all-consuming love. I took him and loved him and I loved all the bad parts as well as all the good parts. To me, he was the most perfect human being.”

As she finally began to emerge from the lowest depths of her grief, it was Liz’s son who told her she had to start engaging with the outside world again. “This is just stupid, Mum,” he told her. He set up a profile for her on Facebook. This was 2009 and Liz didn’t know what Facebook was.

One day she left a comment below a friend’s post - she can’t remember what, something throwaway - and someone replied to her. His name was Paul Hooper, and he was a friend of a friend. Liz responded to Paul’s response, and he responded again. Then he sent her a friend request.

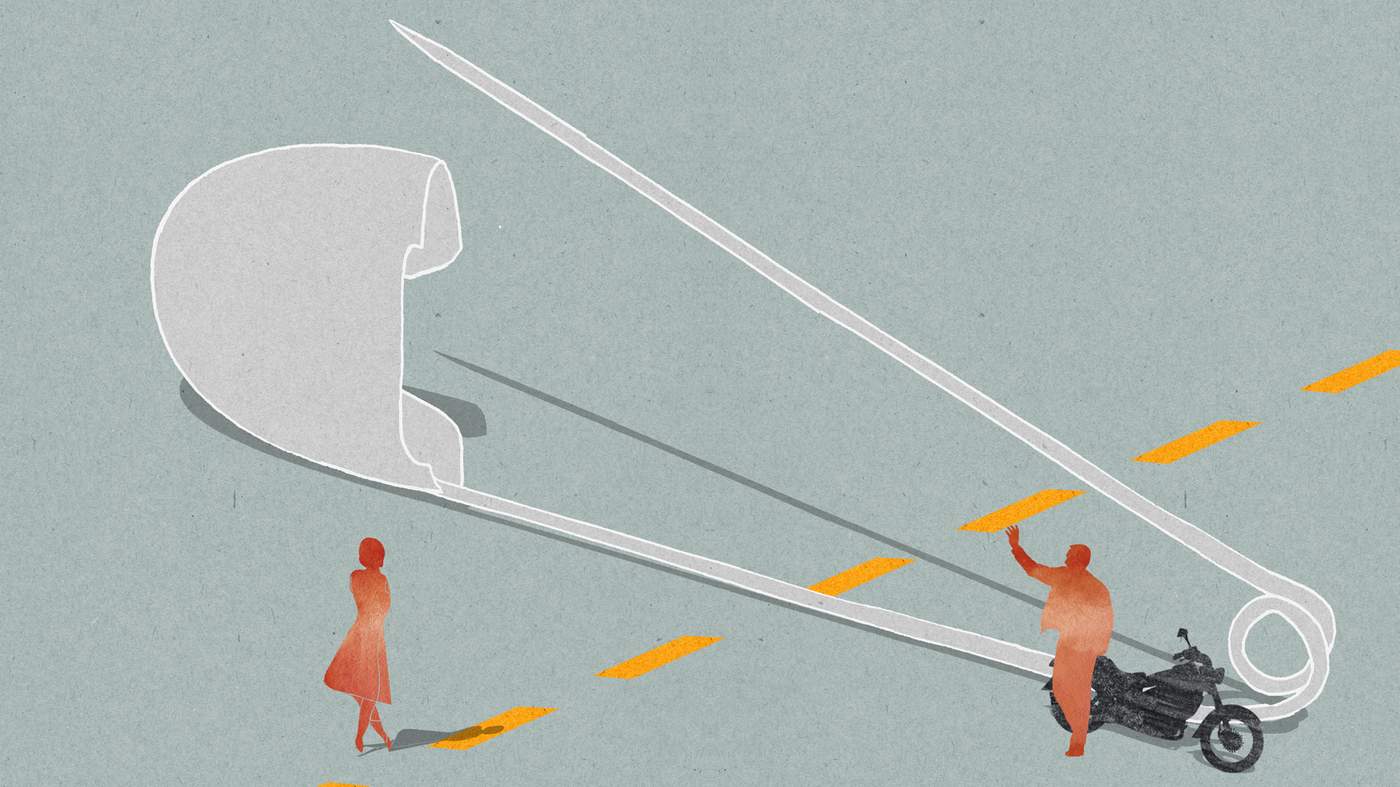

They exchanged private messages - “How old are you?”, “I keep dogs”, “I love dogs too” - and private messaging turned into texting and texting turned into phone calls, two or three times a day. They spoke about their childhoods and Liz mentioned that she was a widow. Then Paul happened to mention, in passing, that he was “poorly”. You can’t just say something like that and leave it hanging there, Liz told him. Poorly with what? Paul told her he was a haemophiliac.

She explained that she knew all about the condition, told him about her late husband. “I’d lived with it so there was nothing he could tell me that would shock me.”

The coincidence was striking. “I wasn’t looking for another husband, let alone a husband that had haemophilia,” she says. But that was how things turned out.

One weekend, Paul and Liz travelled up to Cambridgeshire to the house of a friend of Liz's. When they finally met in person, it was apparent from the start they were quite different characters - Paul a quiet, taciturn Brummie, Liz more gregarious, an outdoorsy type. But they hit it off immediately.

“It was like a coming-together of two old friends that had been brought up together,” says Liz. “It was like I’d known him for years.”

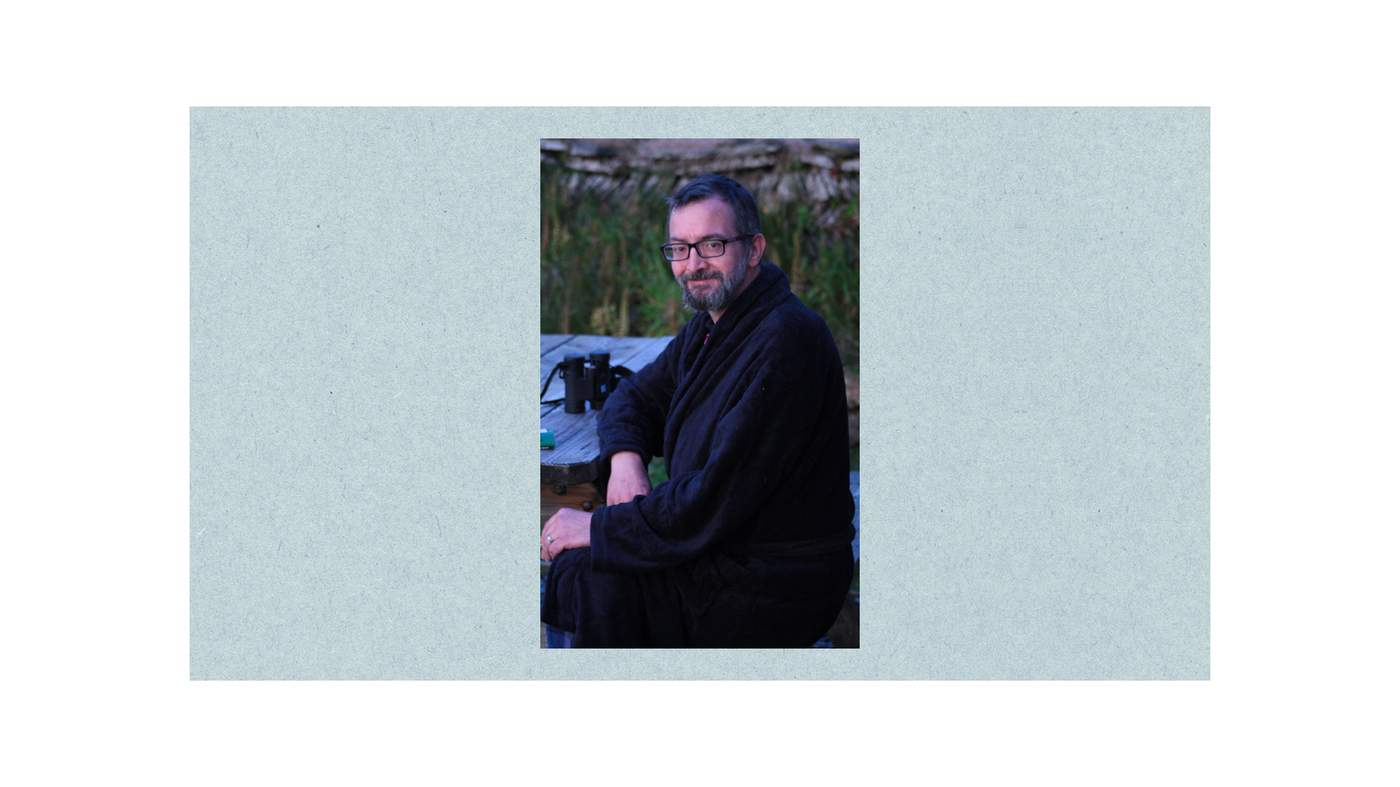

He was gently spoken with a quick, dry wit. He called Liz his “posh bird”. To her, he was “Hoops”. He’d stand up when ladies entered the room. He was quite unlike anyone she'd met before. “He was the opposite to Jeremy,” she says. He wasn't particularly outgoing. He wasn’t much interested in material possessions either, apart from his beloved cameras, which went everywhere with him.

Before their relationship became physical, Paul mentioned that he had HIV as well as hepatitis C - he was one of about 1,250 haemophiliacs infected with both as a result of the contaminated blood scandal. Liz didn’t have any experience of HIV, but she knew it wasn’t something she had to worry about as long as the two of them used protection.

Paul William Hooper was born on 16 January 1964 in Birmingham, and unlike Jeremy - who had no close relatives with the condition - everyone around him had been acutely conscious of his haemophilia from birth. His grandfather and a cousin had it too and, instead of attending a mainstream school, Paul was sent to one for children with physical disabilities.

He’d worked as a civil servant, but had been made redundant after his employers found out he was HIV-positive. He always described himself as “medically retired”. He kept himself busy with activism. He was part of the campaign to get to the bottom of why the contaminated blood scandal had happened in the first place. He’d go on demonstrations and visit Downing Street bearing petitions demanding answers.

But beyond his campaigning, Paul had become somewhat reclusive since losing his job - in fact, he’d barely left the house after he was mugged twice near his home in Walsall. Both he and Liz were emerging from dark periods of isolation when they met each other. He’d stopped taking combination-therapy drugs for his HIV until Liz told him he was being selfish and ordered him to go back on them.

“We saved one another,” Liz says. “We came together at a time when we both needed one another. He helped me crawl out of that horrible place I was in.”

Liz could always recall the date of every significant anniversary with Jeremy. But with Paul it always felt to her as though the calendar was irrelevant and time was out of sync. “It was like - we got married in 2011, but we’d known each other since 1896,” she says. “The first time that we met, it was almost like we’d just carried on a conversation we’d been having a few years before.”

By the time they moved in together in Kineton, Liz and Paul had settled into the routine of a happy middle-aged couple. Paul’s mobility was much better than Jeremy’s had been, and they’d go bimbling - a Brummieism of Paul’s meaning “wandering semi-aimlessly” - around the shops in Stratford-upon-Avon, and take trips to Bath and Paris. There was a village near their home called Wellesbourne that had a small airfield, and they’d go to watch the planes take off and land.

While his movement was better than Jeremy’s, overall Paul’s illness had a much greater impact on his life. There were endless hospital visits and check-ups - for the HIV, the hepatitis C and the haemophilia. Paul couldn’t drive so Liz would have to accompany him to the clinics. She was learning for the first time the scale of the contaminated blood scandal. “Paul really opened my eyes to it,” she says.

On one occasion a doctor mentioned that he had high blood pressure. Then one morning in November 2015, Paul woke up with a headache that wouldn’t go away. When it finally cleared up, he told Liz he had a “wiggle” in his line of sight. Eventually, it turned into a blind spot. When he went to the hospital to get it checked out, the doctors found his blood pressure had sky-rocketed. He’d had a stroke, and his eyesight deteriorated over the next few months to the point where he was registered blind.

Paul’s loss of sight transformed the couple’s relationship. Bimbling around town was no longer possible. Paul was terrified of making a fool of himself and didn’t like to leave the house much. Liz dressed him, cut up his food, trimmed his beard. Doing his injections became a task that took hours. It brought them close together, but they were trapped indoors. The most devastating thing for Paul was that he could no longer make his posh bird a cup of tea.

One day they made a rare visit to a cafe in Wellesbourne. Paul wore wrap-around dark glasses because the sunlight hurt his eyes. It was the first time since he’d lost his sight that he’d eaten out. He was worried about spilling food all over his plate. Paul ate his scampi and chips and drank his tea and listened to the planes landing, and he began crying.

Paul’s health was now precarious. He’d have seizures and, one day when he had been hospitalised for sepsis, a doctor warned Liz that he could die at five minutes’ notice. But somehow he kept bouncing back. His sight was gone for good but his sense of humour was intact. Over time Paul and Liz settled into a kind of routine. She was optimistic. “He’d be back to being my Hoops,” Liz says.“Going about his business, laughing and joking and taking the mickey out of me and making me laugh.”

One morning Paul woke up and told Liz he didn’t want breakfast, as he was feeling a bit bloated. Liz didn’t think much of it. Paul had seemed to be having one of his better phases health-wise, and the two of them had been planning a week’s holiday in Devon together. She left him in bed and popped out to walk the dogs.

When she returned, half an hour later, she realised he was iller than either of them had thought. He vomited on the bed and lost control of his bowels. Liz helped him up on to a commode they kept in the room, stripped him off and began cleaning him up. “I’m all right, I’m all right,” he insisted, but Liz thought otherwise. She dialled 999.

A paramedic was on the scene within minutes and, after checking Paul, he called an air ambulance. The helicopter landed on a playing field next to their house. Liz held her husband, his head on her chest, as the house became filled with people and noise.

“Don’t you be dying on me, Hoopy,” Liz told Paul.

“Don’t be daft, you silly woman. I’m not going anywhere.”

There were now so many medical staff in the bedroom that there wasn’t room for Liz. From downstairs, she could hear all hell breaking loose. A doctor emerged to tell her that Paul had had a cardiac arrest and they had resuscitated him with a defibrillator. “Prepare yourself for the worst,” the doctor told Liz.

Paul was raced to hospital and Liz followed. When she arrived, the doctors told her that he’d had two more cardiac arrests on the way. There wasn’t much more they could do for him. Liz went into the intensive care unit to say her goodbyes. He wasn't conscious and unlike Jeremy, when she'd last seen him, Paul looked peaceful. Liz told him that she loved him, that he wasn’t to worry, that she would take care of everything.

Liz had known from the early days of their relationship that she was likely to outlive Paul but he'd been in a good place when he died, apart from his blindness. “I knew that he was not going to be with me forever,” she says. “In my naivety, I suppose, I just thought I’d get him a bit longer.”

Paul died on 1 December 2017. He was 53. On his death certificate, hepatitis C was listed among the causes. For the second time in less than a decade, the tainted blood scandal had left Liz bereaved.

In the small cottage she shared with Paul, Liz sits on her sofa and sips from a mug of tea. A pendant containing some of Paul’s ashes hangs around her neck. Six months have passed since she lost him, but grief hasn’t yet consumed her. There has been too much to sort out and too much to process. She has cried, but she hasn’t yet fallen to her knees and sobbed her heart out, as she knows she will.

“At the moment, you’re meeting me in that phase I was in with Jeremy where I knew I had to get my son safe,” she tells me. “I’m marching. My feet are going one in front of the other. When I get to that point, and not until I get to that point, can I allow myself to stop and think about what’s actually gone on.”

As Liz was Paul’s full-time carer, most of her income died with him. There were seven years left on their mortgage and now the house is on the market. When the sale goes through she will move in with her mother, who lives nearby, and then she will begin to grieve. “It’s like deja vu,” she says. “But I’m taking my anti-depressants, and I’m not going back to that place I was in with Jeremy. I do not want to hit that wall, which is a very real fear for me.”

While she hasn’t had long to mourn, Liz has had a little time to reflect on the public inquiry into the use of infected blood that recently began its investigative work. Chaired by Sir Brian Langstaff, it is the culmination of decades of campaigning by victims and their loved ones. According to the pressure group Tainted Blood, Paul is one of more than 70 victims who died between the government announcing the inquiry would take place and it actually beginning.

She isn’t interested in compensation. Nor is she getting her hopes up that the inquiry will deliver justice, or indeed answers. The entire contaminated blood community has been through too many disappointments for that. But she desperately hopes it does.

“We’ve been hurt in the most horrific ways. Our menfolk have been killed in the most horrific manner - they’ve been poisoned and slowly allowed to die," she says.

“I mean, Jeremy, for God’s sake, bloody bleeding to death, you can’t begin to imagine. My Paul, Hoops, lying on the bedroom floor, covered in vomit and crap, just bloody horrendous. They were both fantastic men, they were salt-of-the-Earth, God’s honest-to-goodness men who deserved their lives, they didn’t deserve what they had done to them.”

She knows that she isn't a political animal, the kind of person who could go to London and campaign and lobby her MP. She’s used to trees and open space, not people and brickwork. All she can do for her husbands is let the world know who they were, she tells me.

"Use my words," she says, quietly and firmly.

"Use as much as you want. Tell everyone what happened to Paul and Jeremy.

“I’m bloody honoured to have known both of them, I really am. I’ve been a privileged, privileged woman. I had my first love and I had my soulmate. They’ll always be with me and I will love both of them equally and my heart overflows with love for the pair of them. They’re amazing men, and they need their stories told, both of them.”