This article contains images of dead bodies

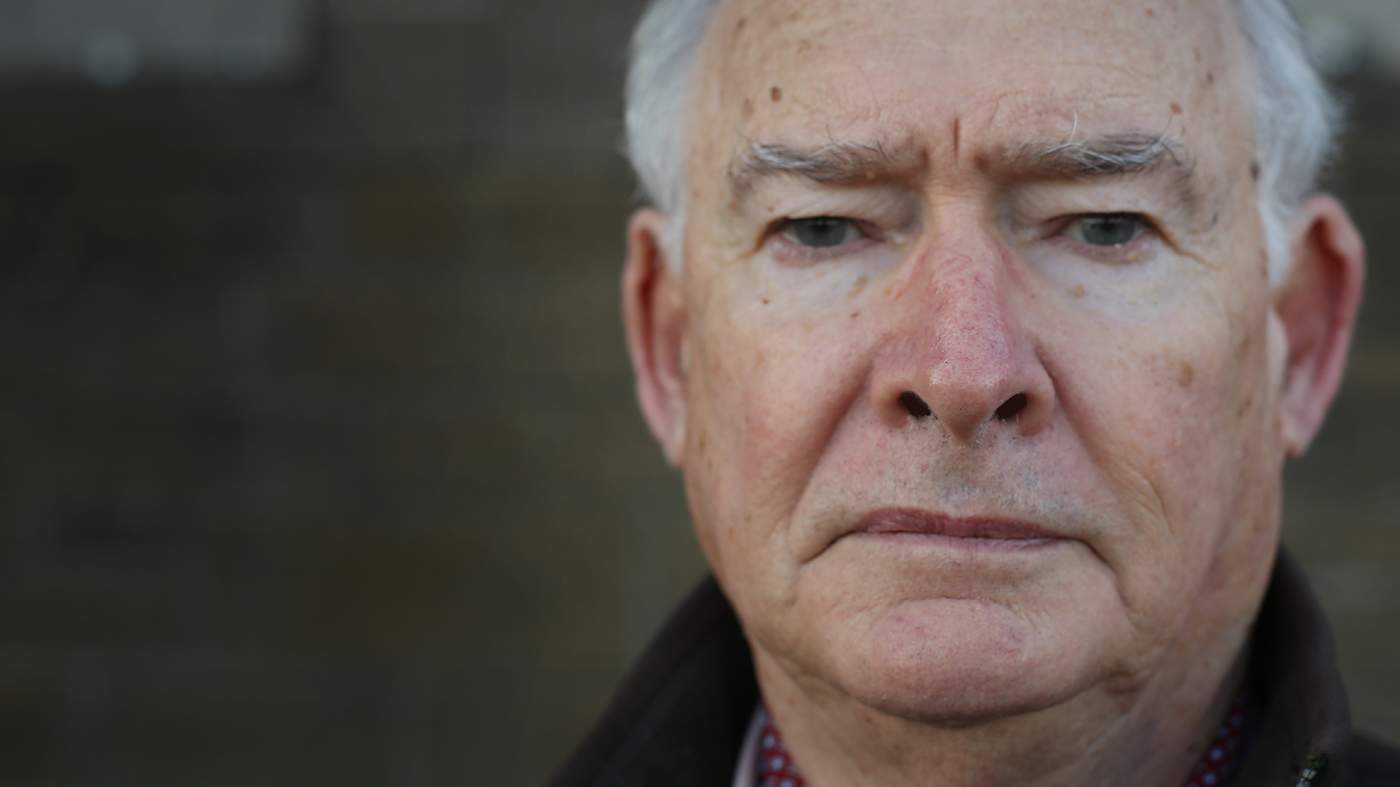

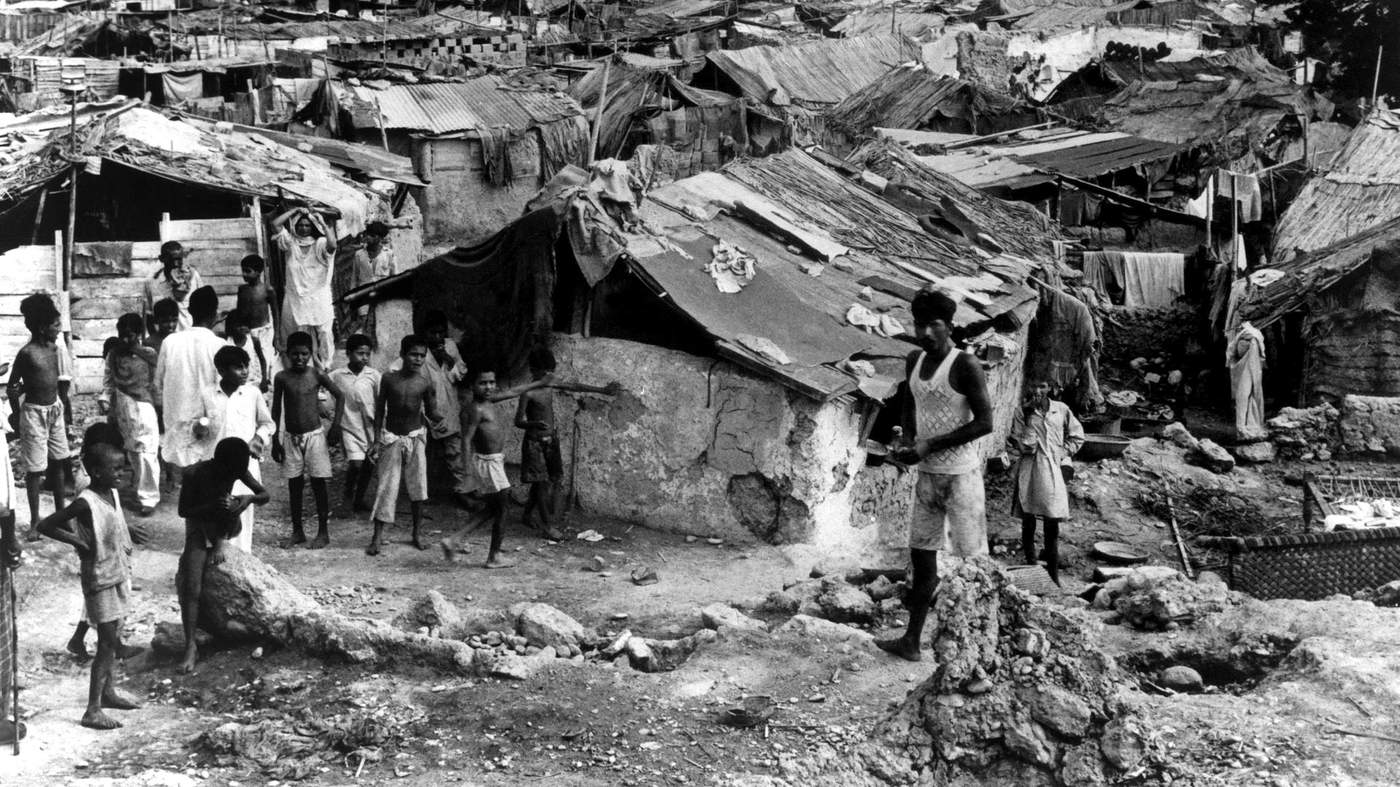

In the weeks before the British left colonial India in the summer of 1947, Ken Miln fished as he always did on the Hooghly river outside Calcutta.

He was 11 years old and in a dinghy with boatmen, concentrating on hooking a big catch. Dead bodies floated past. Using the butt of his fishing rod, he pushed one away.

That may sound awful but we got that used to seeing bodies, not only in the river but on the streets.”

Ken with a catch from the river

“In Calcutta and in the bazaar, the place at times was littered with bodies - children's bodies, too. So a dead body, although an awful thing, didn't really terrify me.”

Ken's parents were from Dundee and were known as jute wallahs. They ran the jute mills around Calcutta, where stems from jute plants were processed ready to be turned into rope or woven into sacking.

They'd been living in India since 1923. 91�ȱ� was in a compound with other British families, surrounded by three high walls. The remaining side led directly to the Hooghly river.

Ken's parents

Just outside the compound was a bazaar, with its fresh fish and food stalls, fakirs (religious people), and sound of loud Bengali music.

Elephants and water buffaloes would drink from the Hooghly. Ken was told not to go down to the river, but from an early age spent most of his time there.

He would also take part in daily baat sessions - conversations with his family's Muslim and Hindu servants. They would then sit on the back verandah gossiping, and reminiscing about life in their home towns.

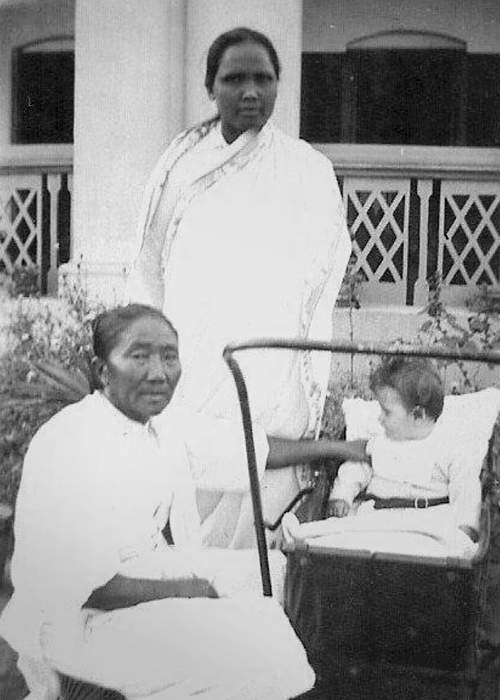

The first words Ken spoke were Hindi - taught by his beloved nanny, or ayah, called Bhutia.

“My first memory was the smell of Bhutia. Her cotton sari usually had the smell of mustard oil, which most Bengalis spread over their body. I grew up with that smell. It eased me," he says.

Ken with Bhutia (seated)

Every other day, Ken ventured outside the compound to the bazaar. He would visit the stalls with local Bengali boys.

Close by, there was an ornate mosque and two Hindu temples. “I can't recall any animosity,” he says.

Ken with local children

But things began to change around the summer of 1946, when Ken was 10.

The baat, or conversation sessions the servants shared, ended abruptly. At night Ken would hear screams, and could see fires burning beyond the compound. At times, there was the sound of gunfire from the bazaar.

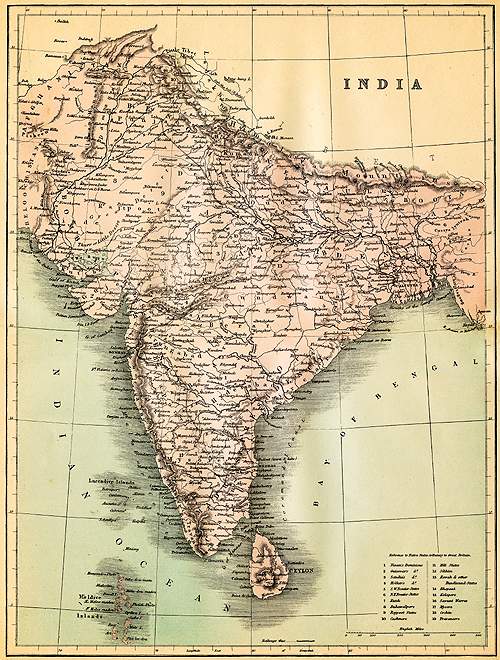

Britain had been the dominant power in India for 200 years.

The Congress Party - led by Jawaharlal Nehru - wanted the British to leave and an India that was united.

The leader of the Muslim League - Muhammad Ali Jinnah - wanted the British out, but was bitterly at odds with Nehru.

He felt India's 100 million Muslims - a quarter of the population - would be marginalised by the Hindu majority.

He demanded safeguards - even a separate homeland for India's Muslims.

In the summer of 1946, Jinnah called a day of action which sparked the Great Calcutta Killings - riots between Muslims and Hindus that left thousands dead.

The riots affected Ken's village, 20 miles from the city.

He still has nightmares about a particular incident he witnessed.

Some of the workers from the jute mill got into a fight. Ken doesn't recall whether they were Hindu or Muslim.

“There were two men with lathis - bamboo poles - and they beat the other two over the head. They killed them.”

Communal riots were spreading beyond Calcutta and across northern India. This uncontrolled violence was interpreted by the British as irreconcilable differences between Hindus and Muslims.

In late 1946, the UK's Labour government - its exchequer exhausted by World War Two - had decided to end British rule in India.

In June 1947, the last Viceroy to India, Lord Mountbatten, announced the country would be partitioned.

The Punjab region in the West, and Bengal in the East - both of which for centuries had been melting pots of religions and cultures - were to be divided.

Lord Mountbatten at Viceroy House in New Delhi

(Getty Images)

Mountbatten stunned everyone by saying the transfer date would be August.

India would be divided in a breathtaking 11 weeks, leading to the creation of the independent nations of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Bengal - where Ken lived - had seen some of the worst violence in the year leading up to the split.

But the violence preceding partition was nothing compared with what was to follow. Authorities on all sides were completely unprepared.

Millions of Muslims moved to West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Millions of Hindus and Sikhs travelled to be within India's new borders. It would become one of the largest mass migrations in history.

People who had co-existed for centuries turned on one another. Hundreds of thousands lost their lives, and tens of thousands of women on all sides were raped and abducted.

The Punjab was to become a bloodbath.

The riots affected Ken's village, 20 miles from the city.

He still has nightmares about a particular incident he witnessed.

Some of the workers from the jute mill got into a fight. Ken doesn't recall whether they were Hindu or Muslim.

“There were two men with lathis - bamboo poles - and they beat the other two over the head. They killed them.”

The riots between Muslims and Sikhs and Hindus were spreading beyond Calcutta and across northern India. This uncontrolled violence was interpreted by the British as irreconcilable differences between Hindus and Muslims.

In late 1946, the UK's Labour government - its exchequer exhausted by World War Two - had decided to end British rule in India.

Lord Mountbatten at Viceroy House in New Delhi

(Getty Images)

In June 1947 the last Viceroy to India, Lord Mountbatten, announced the country would be partitioned.

The Punjab region in the West, and Bengal in the East - both of which for centuries had been melting pots of religions and cultures - were to be divided.

Map of British colonial India

(Getty Images)

Mountbatten stunned everyone by saying the transfer date would be August.

India would be divided in a breathtaking 11 weeks, leading to the creation of the independent nations of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Bengal - where Ken lived - had seen some of the worst violence in the year leading up to partition.

But the violence preceding partition was nothing compared with what was to follow. Authorities on all sides were completely unprepared.

Millions of Muslims moved to West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Millions of Hindus and Sikhs travelled to be within India's new borders. It would become one of the largest mass migrations in history.

People who had co-existed for centuries turned on one another. Hundreds of thousands lost their lives and tens of thousands of women on all sides were raped and abducted.

The Punjab was to become a bloodbath.

Legacy life

Dr Veena Dhillon

from Edinburgh

After Amar Kaur Dhillon died, Veena found a poem that her mother had written describing her wedding night and how she had to flee the next day.

It was in a collection of papers in an old ring binder found in Amar's flat. It included poems and essays from a time in her life that she rarely spoke of while she was alive - partition.

In August 1947, Veena's parents were living in Western Punjab, which now belongs to Pakistan.

Dad was very unwilling to talk about partition. He was traumatised by it. Only when he had dementia did he start talking about it.”

In one poem - The Night of the Flight - Veena's mother describes spending her wedding night on the roof of her new home under the “twinkling” stars, and how the next morning they were forced to flee for India:

You were young

I was young

We were young and in love

Nothing mattered

Spoil and scatter of '47

Meant nothing

We dwelt in another world

The world of love of intoxication

In a fashion

It was our first night together

The night before the flight

From ancestral home

We lay face to face

Under the blue dome

And drank from the moon

Its milky moonlight

In it we watched

Many stars twinkling in our eyes

Yours and mine

We watched and watched

All night with such a delight

Unslept the whole night

Crack of dawn the message arrived

“Be ready, we are going”

Going?

Where?

Why?

Questions... nobody answered!

Hush on lips

Anxiety in mind

Breakfast?

Packing?

Nobody bothered "Hurry, hurry, quick

Trucks are moving - no time

For leaving message for the left behind"

Nears and dears

Mothers, fathers

Trucks were moving, military truck

Evacuating, dwellers of stately homes,

Women and children and some men

Their guardians

Refugees!

“I think she was really keen that family history should not be forgotten, because in lots of ways I am rootless," says Veena.

"I’ve never been to the geography of the place where probably my family and my ancestors lived for almost certainly centuries.”

Perhaps she was trying to give something to us because I don’t have a root.”

Veena admits her find - which details her parents' journey, life as refugees, and how her grandmother died of cholera immediately after leaving Pakistan - is a piece of the jigsaw.

“It’s a little bit of the root.”

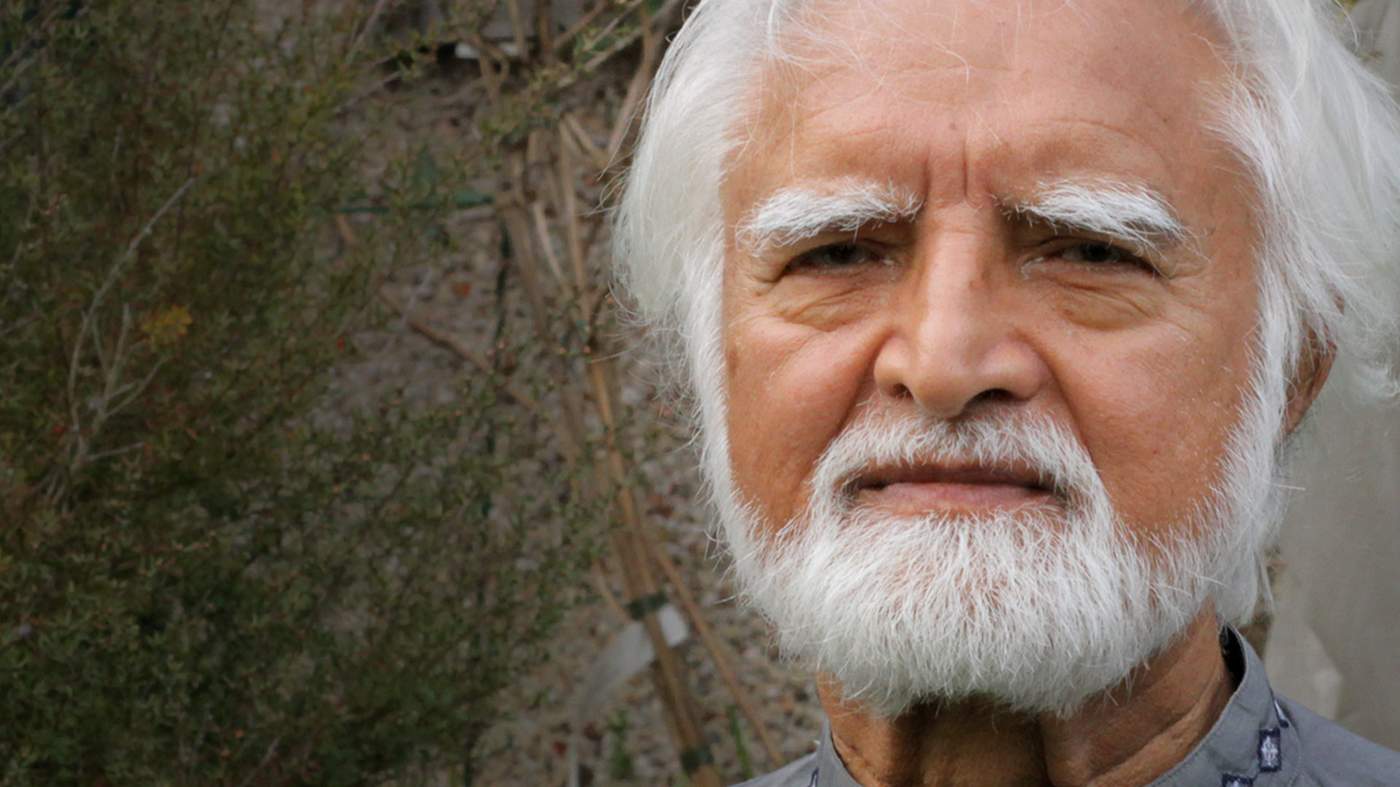

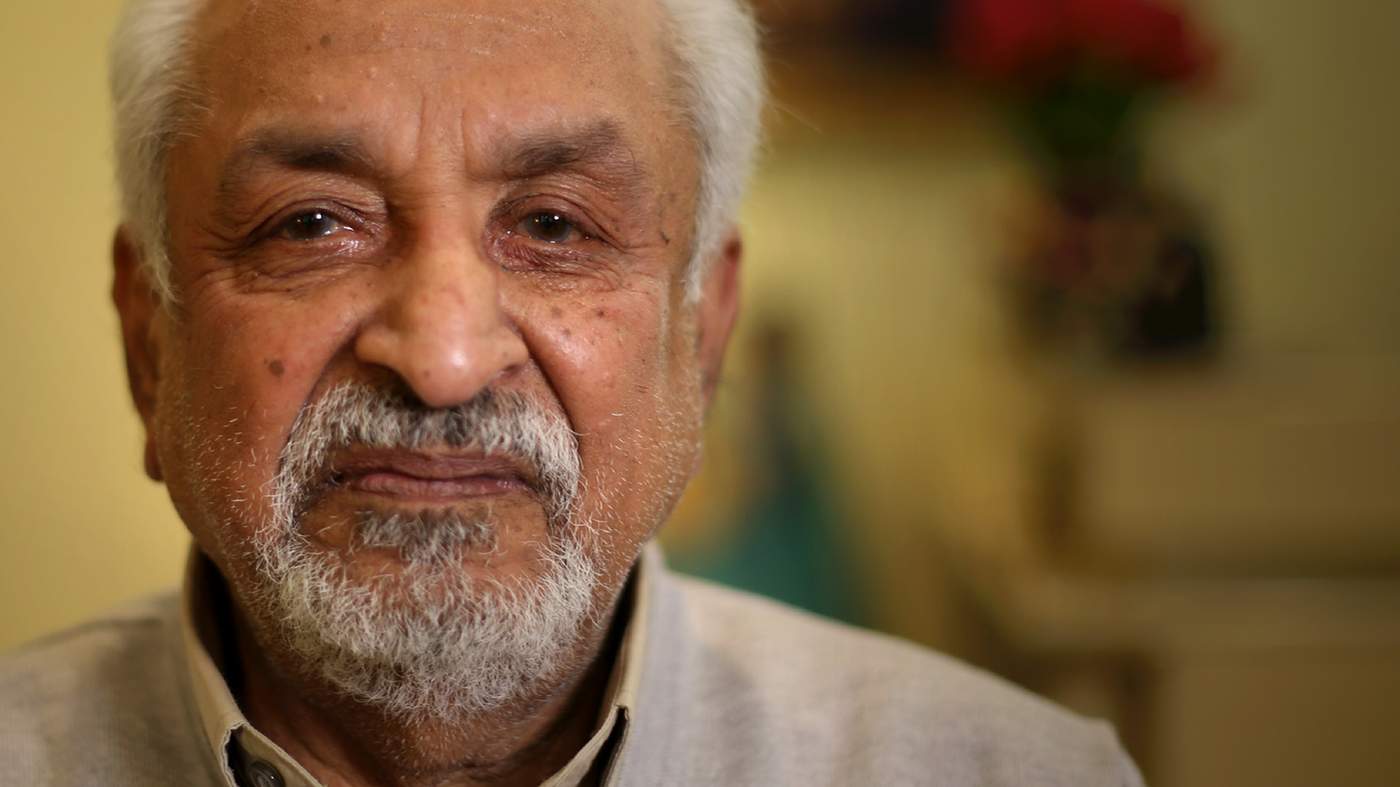

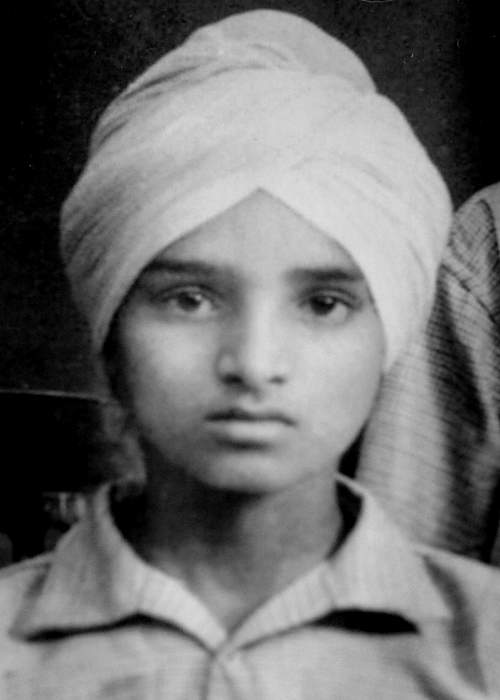

Gurbakhsh Garcha was at school on the day India won independence from Britain. It was 15 August 1947.

The 12-year-old boy in the Punjab village of Dhandari Khurd near Ludhiana recalls celebrations, and sweets being handed out.

Gurbakhsh as a boy

But he also remembers that many of the villagers weren't quite sure what independence meant.

They wanted Nehru to be King. To them a new government was a king. They had only lived under a monarch until then.”

Two days after independence, Gurbakhsh and around 50 men sat around the one wireless in the village to listen to All India Radio.

There was an announcement of where the borders were to be drawn. The atmosphere was tense.

His village was safely within India. Then there were gasps of disbelief.

“When it was declared that Lahore had gone to Pakistan, I could see people in my village, elderly people, crying,” he says.

They didn't want Lahore to go, it was a big prize.”

“Lahore was Punjab's most cosmopolitan city, with a very large Hindu and Sikh population.”

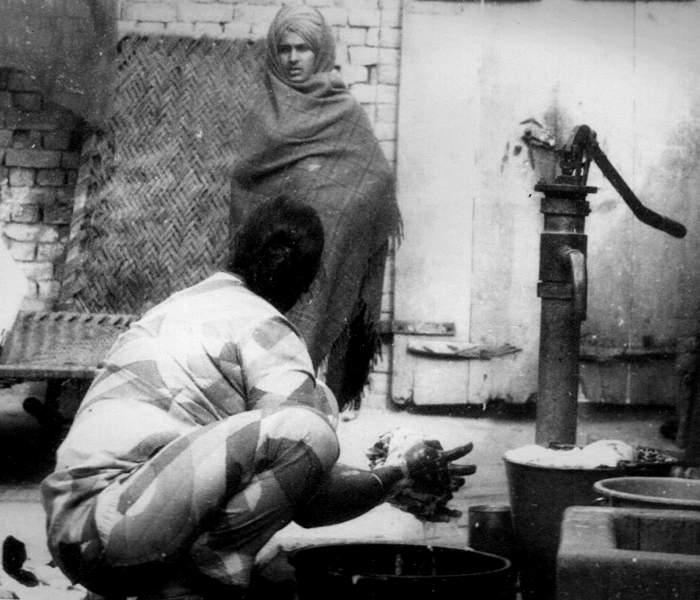

Gurbakhsh's village was small.

Sikh elders under the banyan tree in Gurbakhsh's village

There were 150 people - mostly Sikh like Gurbakhsh, a quarter Muslim and only one Hindu family.

“My childhood was really wonderful. We had open streets to run around in. I could go into anybody's house - there wasn't a tree around the village I hadn't climbed.”

It was a harmonious, tight-knit community.

“We didn't really think about religion very much. It was a fairly close relationship all the time. We never thought 'one day we'll have to separate from each other'.”

Old photos from Gurbakhsh's village

Soon after partition, things changed.

Posters went up on the walls and trees inciting violence, saying anyone who wanted Pakistan would meet their “kabristan” - Muslim burial ground. Then the attacks started “by the Sikh gangs who carried swords and spears”.

These mobs came from outside the village looking for Muslims.

Gurbakhsh's teacher and two sons were slaughtered and many of his Muslim neighbours began to move out.

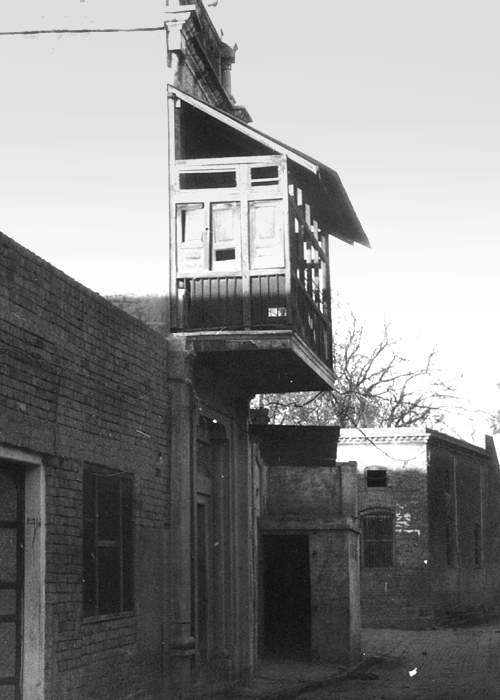

Gurbakhsh's childhood home

There is one goodbye Gurbakhsh cannot forget.

His uncle's mother had died and one of her best friends, a Muslim neighbour they all called Mai, had raised Gurbakhsh's uncle and his brothers as her own - even suckling them.

Gurbakhsh would see her when he was playing with his cousins.

“Mai would bathe me when I was young. Her sons would carry me to her farm. Family relations were very, very close.”

He remembers everyone crying as they said their goodbyes.

Mai took Gurbakhsh in her arms and said they would return. She handed the keys to her house to Gurbakhsh's uncle.

“They all thought they would be back. My uncle had the keys to the house for years afterwards. He wouldn't let anybody near the house til it became quite obvious there was no way they were coming back.”

The village was on the main railway line from Delhi to Lahore.

Gurbakhsh's family were farmers, and one of their fields was 20 yards from the tracks.

Trains would pass carrying refugees from both sides of the border.

It was really horrific because we started seeing trains going very slowly, doors open, bodies hanging out. Some dead, some dying, smeared in blood.”

One day he saw something unusual. Life amidst death.

A dishevelled woman with two small children fell off one of the trains. She crossed the fields, and Gurbakhsh and other villagers crowded round them.

The woman was Muslim. The Sikh women of the village took her to a farm building for her protection.

She was crying all the time and clinging on to her two children and just saying continuously 'Allah will help, Allah will save us'.”

“She was frightened, just a victim. She had no idea what would happen to her. The villagers said: ‘Don't worry, you're safe here. Do you need food? Can we give you any clothes and things?’

“She refused the offers, only accepting milk for her children.

“People hadn't lost their humanity, especially women.

“The future must have looked quite bleak in her situation with that sort of carnage going on.”

A few days later the villagers organised with the police to take her and the two children to a safe camp near the border.

Posters were now going up urging respect for all religions.

But it was too late.

Refugees board an Indian train bound for Pakistan

(Getty Images)

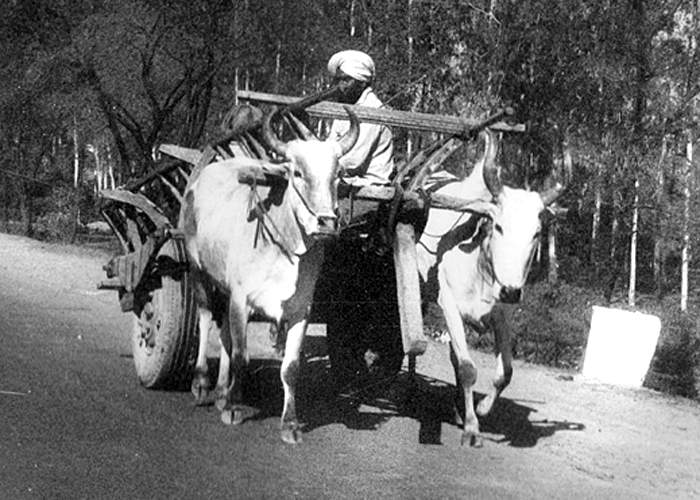

Across the Punjab, millions of people were journeying not only by train, but also by foot. Muslims were leaving the Indian Punjab for Pakistan - while Hindus and Sikhs moved in the opposite direction.

Gurbakhsh recalls the long lines of refugees stretching in both directions.

“They had bullock carts and several hundred people travelled together for safety.”

They would sleep on the road, some camping in the groundnut fields.

Resting on a journey to Pakistan

during partition

(Getty Images)

A year later, Gurbakhsh and his grandfather were weeding together in the fields.

The grandfather noticed that the groundnut crop was surprisingly lush in certain, seemingly random, patches of the field.

They discovered that the crops had been fertilised by the bodies of refugees - the frail, the sick, the young - who had died on their journey and been buried in shallow graves.

“My grandfather said you must not disturb them. It is their place of rest.”

Gurbakhsh says partition has left its mark on him.

“Your whole psyche changes when you are living through that sort of thing. I don't think you are normal any more having seen such horrid things. You just slowly change and come to accept what is happening around you. My faith in humanity is shaken.”

Legacy life

Tara Parashar

from Birmingham

Tara was in Delhi, clearing the house of her recently deceased grandfather, when she found some smashed photo frames.

“They were quite big, covered in mould and really dirty.”

She took the photograph out of the frame, cleaned away the dirt, and saw - what she now knows to be - the staff of the last Viceroy to India.

In the front row were Lord and Lady Mountbatten, with Tara's grandfather in the row behind.

Tara's grandfather is second from left in the back row

“I felt like, 'What is going on here?' It made me really interested in the story behind this photograph.”

Tara discovered that her grandfather had been a close aide to Lord Mountbatten in the run up to partition.

She knew nothing about this part of his life.

“He wouldn’t really talk about partition. He wouldn’t really talk about all the high-society parties that he went to with the Mountbattens. One thing he did reflect on, was that sense of sadness of missing your home.”

Tara's grandfather was Hindu and born in what is now Pakistan.

Tara found out from a newspaper report that he had made a daring dash across the border on his motorbike to save his relatives.

She later learned that many of the relatives owed their lives to him - but they had never told her how they had been rescued.

The silence about partition started with my grandfather, and that silence has come through the rest of the family.”

In the garden of the house in Delhi lies one tile that does not match the rest.

It was the only thing rescued from the original family home in Pakistan.

“That tile is something we all have and says we came from this place. It’s part of our story,” says Tara.

But so much is still shrouded in mystery. Tara has only just learnt her grandfather kept in touch with a Muslim school friend from Pakistan over the years since partition. They met for the first time in 2000.

She is now trying to piece together her grandfather’s history, to build a sense of attachment to her homeland.

As a second generation British Asian, this has a particular poignancy.

“When you’re British Asian sometimes you’re too British and sometimes you’re too Asian. I think it’s important to have a sense of where you belong.”

She thinks the history of partition should be taught in UK schools.

“So British people understand why the country looks the way it does. Maybe people would relate to each other better.”

She also thinks it's important that Britain's South Asian communities understand the history of partition and not just their own narrative of it.

“From the outside looking in, it looks like we're one cohesive culture - but actually it's so fragmented. In a sense it does all go back to partition, to the drawing of a line between so many people.”

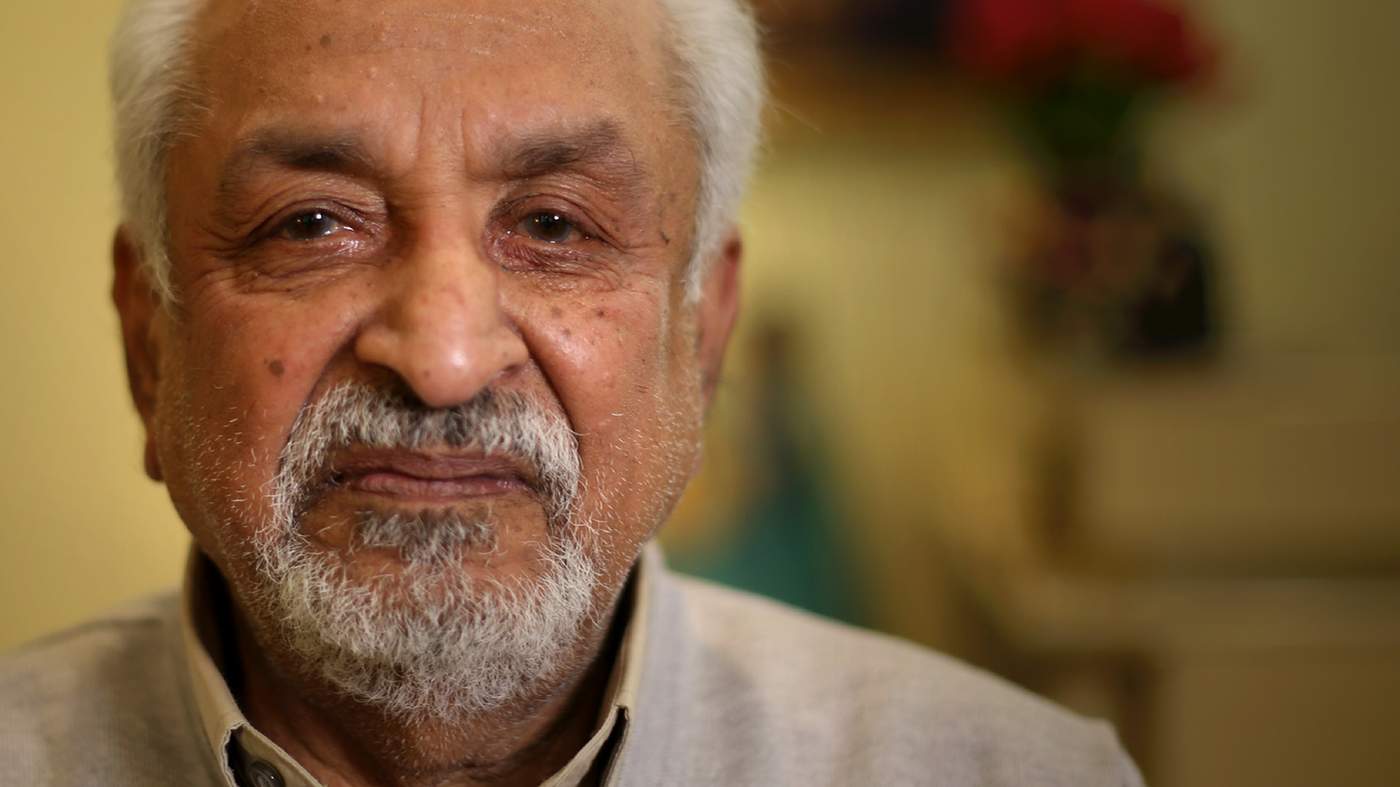

In India's capital, Delhi, 16-year-old Iftkahr Ahmed was alone and scared. It was September 1947.

Muslims were being targeted in the large-scale riots around the capital.

The family he had been staying with had left the city and were afraid to return.

Just a few weeks earlier, Iftkahr had joyfully watched the independence fireworks.

He was Muslim and felt proud of being in India.

I never felt Pakistani - I always said 'I'm Indian'.”

Iftkahr fled where he was staying and found sanctuary with a number of other fellow Muslims.

Soldier at the entrance to Paharganj bazaar during the Delhi riots

(Getty Images)

They used horse carriages and barrels to barricade themselves inside safe houses, but these were frequently set alight by mobs trying to flush out Muslims.

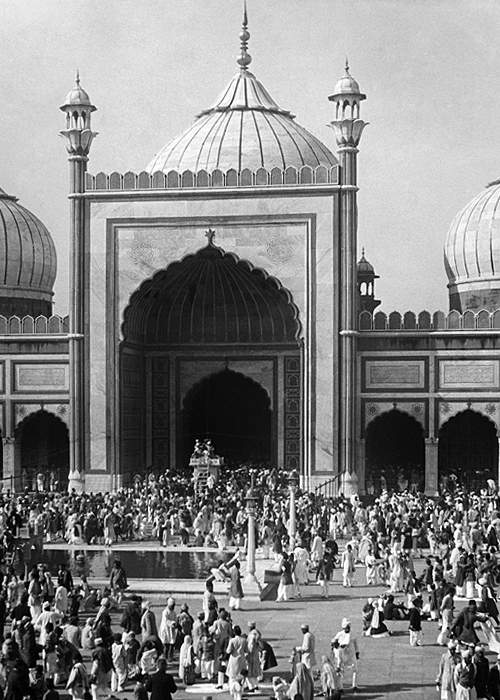

They decided to make their way to the Great Mosque in Delhi, the Jama Masjid, for their safety.

Delhi's Jama Masjid photographed in 1935

(Getty Images)

It was raining continuously, Iftkahr remembers.

“There was not a soul around the streets. Not a fly.”

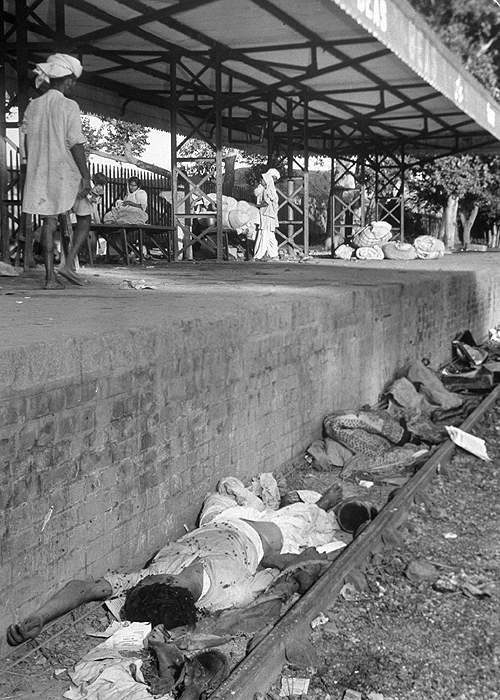

Bodies lay littered on the street, as if they were leaves from the trees.

He then made what he describes as “the biggest journey” of his life.

Members of his group had to walk through a Hindu area.

In every doorway, there were two or three people holding knives and swords.

“They were dying to get us,” he recalls. “We dared not even look up at these men, as eye contact would have meant certain death.”

The Hindu men moved in. “They picked up the young girls,” says Iftkahr.

It is the sound he can't forget.

The screaming. Women were crying out. Their young daughters were going. I cannot describe to you how bad it was and what the conditions of those mothers and fathers were.”

Tens of thousands of women were raped and abducted during this time by men of the “other” religion.

All sides were perpetrators, all sides victims.

Bodies removed from a street after rioting in Delhi

(Getty Images)

Iftkahr carried on walking, looking straight ahead. He thought it was just a matter of time before he and the other Muslims he was travelling with were attacked.

Yet the men and older women managed to get out.

“It was the most frightening moment of my life,” he says.

He made his way to the Mosque, which was packed with people and families. But he only stayed one night as the group decided to move on.

They journeyed to another refuge, which was even worse.

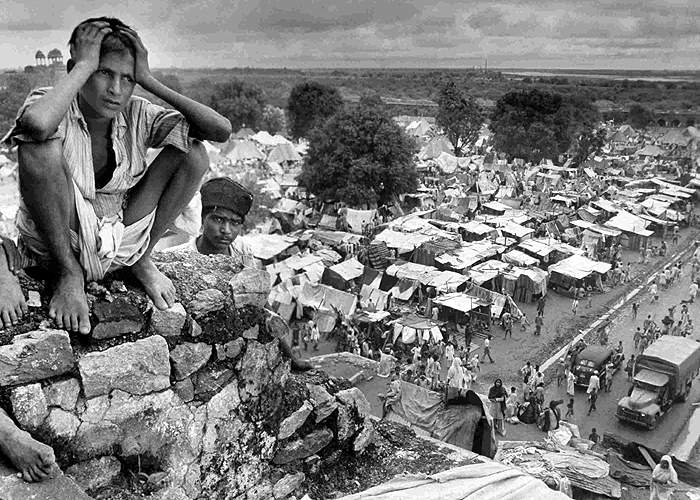

Boy at a refugee camp close to Delhi

(Alamy)

“It was almost like the whole of Delhi was there. It was so horrible - women selling themselves for a piece of bread.”

Iftkahr had no money or food. He hadn't eaten in days. None of the refugees was willing to share food.

He then heard of trains leaving for Pakistan. Many warned him not to go, saying the trains were being targeted by mobs.

“I don't care if I live or die,” he thought. “I am going.”

Train leaves Delhi with staff from the new Pakistan government

(Getty Images)

He made it by train to Attari - a village in the Punjab, only a mile or so from the new Indo-Pakistan border.

The train stopped at the railway station, where people started cooking and setting up a temporary camp on the station platform.

When another train arrived carrying soldiers from Pakistan's army, Iftkahr asked if he could travel with them, saying he was alone and had no luggage.

They took him on board and hid him under the seat away from the officers.

They fed me with dry biscuits and a cup of tea.”

It was the first food and drink he'd had in days.

On arriving in Lahore after dark, he was told: "Son, this is Pakistan. This is your world. Do whatever you want to do.”

Iftkahr finally felt safe. Tiredness overcame him and he fell asleep on the platform.

He awoke early in the morning feeling wet.

The platform was full of people. But they were all dead.

Children, women and men with terrible wounds, all cut up.”

The wet sensation against his skin was their blood.

Iftkahr believes those people had come from the train he left at Attari - and that the passengers had been killed very close to the border. The authorities had unloaded the bodies on to the platform while he slept.

Aftermath of an attack on a refugee train

(Getty Images)

“I used to think I would never reach Pakistan - I knew my death could be round the corner. So when I got to Lahore that morning and found all those dead bodies, I didn't worry about them, I worried about myself.”

He ran from the station and headed to the city. He was shocked by what he saw when he arrived.

“Lahore was all burnt. The complete town was burnt. That's what the Pakistanis did. They burnt the houses and people in them. India did it to us - but Pakistan did it to them. The same. It was tit for tat.”

Legacy life

Husnul Khan

from Surrey

“My grandmother was eight when she made the journey so maybe that was why she told me at that age.”

At the time Husnul couldn’t really comprehend the epic escape from India to Pakistan on foot.

But over time she heard more and her curiosity grew.

Husnul - who has just finished her A-levels - admits she always assumed Pakistan and India had been separate countries, and was surprised to learn they were once part of the same country.

Punjabi is the same language, same culture, but there’s one half in India and one half in Pakistan. It didn’t make sense to me why they separated.”

She thinks that if partition hadn’t happened, her family and other Punjabis would not have come to the UK.

“A lot of people who came here in the 1950s and 60s from the Punjab were not doing so well because of partition. They came here because of that.”

She feels events from 70 years ago still define her grandmother and that whole generation.

Husnul's grandmother

She wants to return to the home her grandmother left in India.

“I feel a connection to all the people who suffered with my grandmother - not just Punjabis, but Bengalis as well. I have a lot of empathy for the Hindus and Sikhs who had to move from Pakistan, and Muslims who moved from India.”

No-one from the family has ever been back.

I want to see the village, I feel a connection to that place. It is good to know where you are from. I want to go back just one time to see it.”

Raj Daswani was 15 and missing his first love Yasmin.

He had left his home in Karachi - in newly-created Pakistan - in early September 1947, and was now in an army barracks outside Bombay in India with 500 other refugees.

Hindu and Sikh women and children arrive at Bombay, having travelled by sea from Pakistan

(Getty Images)

He and his family had arrived with the clothes they wore, and two big tins of fried wheat-flour and ghee - clarified butter.

There was one toilet for all to share outside the barracks. Pigs, rats and snakes were not far away. There was no drainage system.

They slept in a big hall partitioned at night with bed sheets - one so-called “room” for each family. They were given rotten onions, potatoes and lentils to eat.

Life for Raj and his Hindu family back in Karachi had been happy.

Raj (front left) and his family

Raj had known Yasmin, a Muslim girl who lived in the same building, for five years.

They would meet on his terrace. He would light a candle and hold it between them.

“I used to tell her,” he cups his hands, “one day I'll give you this Moon.”

They discussed their future, even marriage.

Life in the city changed once Muslim refugees arrived from India. Raj's family no longer felt safe after fellow Hindus had been attacked.

Their Muslim neighbours, whom they'd known for years, begged them not to leave.

“They were crying. They did not want us to leave. They said you are safe here, we'll safeguard you.”

Leaving Yasmin was “unbearable" he says.

"She was crying. I was crying. We held hands with each other and slowly, slowly, slowly we left each other.”

Her last words to Raj were asking him to come back home one day. His parting image of his home was his love.

“I could see Yasmin looking at me til the end, til she could [no longer] see.”

Raj as a young man

To survive in the army barracks, Raj would go hawking knick-knacks after school - playing cards, combs, cufflinks.

Life carried on. He went to school and enjoyed putting on plays. He also joined a literary group.

One day a fisherman they knew from Karachi arrived.

Raj's father had lent him some money a few years back. The fisherman - who was Muslim - had found out where they were now living and had come to repay his debt.

I could see my father's eyes had tears, that there are such people in this world.”

The man was "welcomed like a family member" and lived with the Daswanis for a week.

They learnt that Muslim refugees from India were living in their old home in Karachi.

“We lost our real brothers, the foreigners have come,” the fisherman told them.

He was also shocked at the family's living conditions in India.

“He had seen our lifestyle in Karachi, and he was seeing the reverse,” says Raj. “Life in the barracks.”

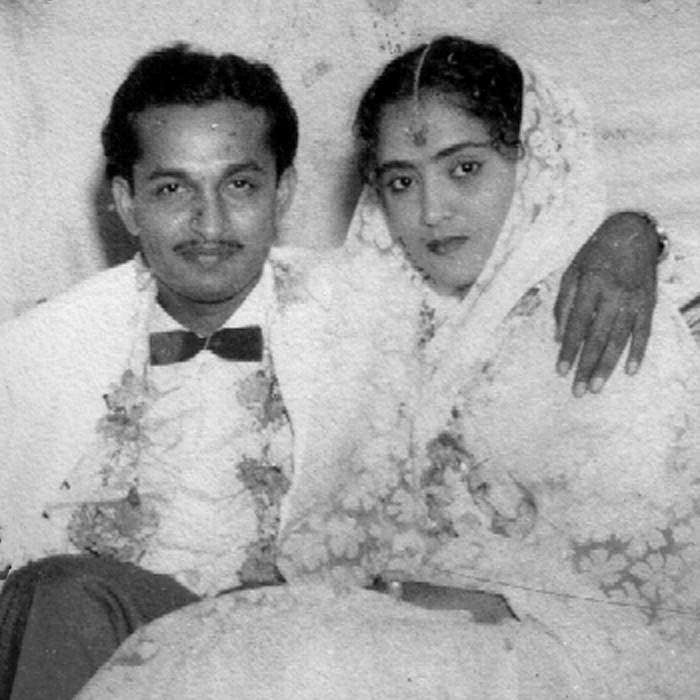

Outside Bombay, Raj met another refugee. A woman, who he says reminded him of Yasmin.

Geeta shared Raj's passion for staging plays.

The couple fell in love and have been together for almost 60 years.

Raj and his wife Geeta on their wedding day

Decades later, Raj kept his word to his teenage sweetheart, Yasmin, and returned to Karachi.

“The first thing I did was to take the dust from the ground and kissed it. I put it to my forehead. I said, 'My mother, I have come back.'”

Raj returned to the family home he had left behind.

It was a dream come true… my place was the same.”

He looked up at the balcony he'd once sat on with Yasmin, but could not face going inside. They were never to meet again.

The building where Raj lived in Karachi

He took stones from the place where he grew up back to London, which he still keeps in his home.

“These stones are with me, as if I'm still connected to my soil,” he says.