There is a hill in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul called Nabi Yunus.

It has been a site of worship for centuries. A monastery was built there in the early Christian period, then, more than 600 years ago, it was converted into a Muslim shrine to the prophet Jonah.

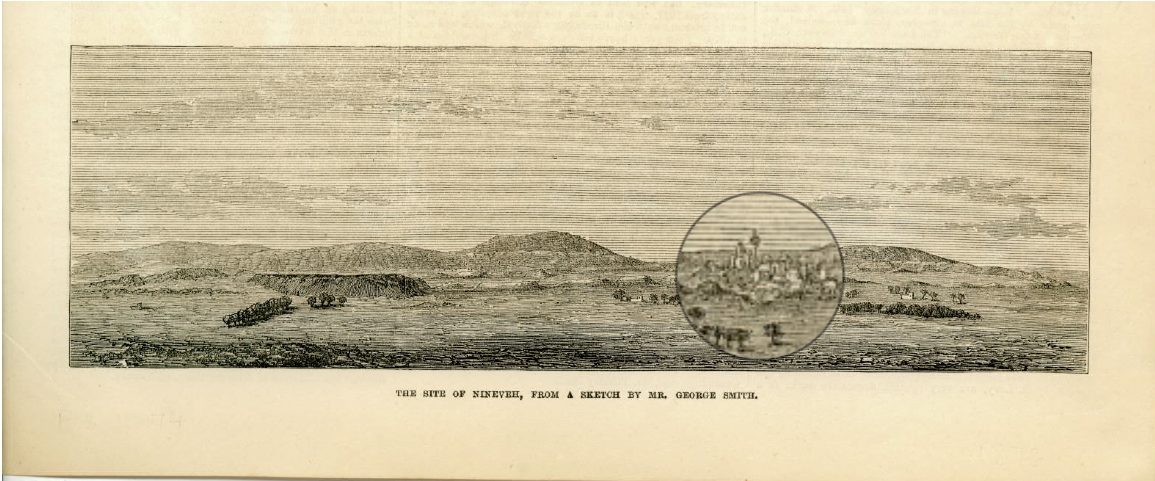

Engraving from Robert Brown's The Countries of the World (1876)

In July 2014 this shrine was blown up by the Islamic State (IS) group.

Militants claimed that Nabi Yunus was no longer a place of prayer but of heresy.

Footage of the explosion was beamed around the world. The message was clear: no holy site, however venerated, was safe from IS’s radical interpretation of the Koran.

But the destruction of Nabi Yunus has far from ended the story of this ancient venerated mound. Instead it has raised fascinating questions about what exactly lies beneath the foundations of the mosque.

In Spring 2018, 91�ȱ� Arabic sent a team into the complex of cool, dusty tunnels recently discovered inside the hill.

They captured high resolution photos of their findings using a technique called photogrammetry and attempted to untangle some of the mysteries that remain unanswered in the aftermath of the destruction.

Located on the edge of what was once the bustling city of Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, Nabi Yunus is Arabic for Prophet Jonah, mentioned in the Koran and the Hebrew Bible.

In both books, Yunus/Jonah travels to Nineveh to warn its citizens that they will be destroyed unless they repent their sins.

Many Muslims believe that the prophet's bones were kept at the site. A shrine was later built. It is thought to contain a tooth from the whale that, according to tradition, swam with Yunus in its belly for three days.

Engraving from Gustave Doré’s illustrated Bible (1886)

"Nabi Yunus has always been one of our most important religious and cultural sites," says Ali Y Al-Juboori, director of Assyrian Studies at the University of Mosul.

"When people visited the hill they could see the best parts of both ancient and modern Mosul."

On 24 July 2014, Islamic State militants placed explosives on the inner and outer walls of the mosque. Militants ordered worshippers to leave. Locals were instructed to stand at least 500 metres (1,640ft) from the building.

Within seconds of the detonation, Nabi Yunus was reduced to rubble. IS expelled Christians from the city. It was an attempt to make Mosul a single religion city for the first time in its history.

A video of the IS bombing of the Nabi Yunus shrine in July 2014

It was part of a spree of destruction of holy sites and icons in Mosul.

At the nearby Nergal Gate to the Ancient City of Nineveh, Islamic State group fighters defaced an ancient statue of a lamassu, a mythical creature that once stood guard at the entrances of Assyrian palaces. And then blew the whole gate up.

They used a jackhammer to bore directly into its placidly smiling face.

IS video of destruction of a lamassu in Northern Iraq

IS partly justified their destruction of Nabi Yunus by attacking the legitimacy of the shrine. "This was a grave of Christian popes," an Islamic State fighter told the 91�ȱ�. "It is forbidden to construct a mosque on a fake shrine."

Academic research does indeed suggest that Yunus was not buried there. In fact, the prophet is reputed to have graves all around the world.

"In the medieval world, with long distance communication being tenuous, many famous ancient people acquired multiple graves at different locations," says Dr Thomas A Carlson, an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University and author of Christianity in Fifteenth-Century Iraq.

In reality the bones attributed to Nabi Yunus probably belonged to a Christian patriarch named Henanisho I of the Church of the East. He was buried in the monastery in 701.

Archaeologists do not yet know whether Henanisho’s bones survived the explosion. But they have discovered artefacts that have been concealed from human sight for millennia.

On 24 July 2014, Islamic State militants placed explosives on the inner and outer walls of the mosque. Militants ordered worshippers to leave. Locals were instructed to stand at least 500 metres (1,640ft) from the building.

Within seconds of the detonation, Nabi Yunus was reduced to rubble. IS expelled Christians from the city. It was an attempt to make Mosul a single religion city for the first time in its history.

A video of the IS bombing of the Nabi Yunus shrine in July 2014

It was part of a spree of destruction of holy sites and icons in Mosul.

At the nearby Nergal Gate to the Ancient City of Nineveh, Islamic State group fighters defaced an ancient statue of a lamassu, a mythical creature that once stood guard at the entrances of Assyrian palaces. And then blew the whole gate up.

They used a jackhammer to bore directly into its placidly smiling face.

IS video of destruction of a Lamassu in Northern Iraq

IS partly justified their destruction of Nabi Yunus by attacking the legitimacy of the shrine. "This was a grave of Christian popes," an Islamic State fighter told the 91�ȱ�. "It is forbidden to construct a mosque on a fake shrine."

Academic research does indeed suggest that Yunus was not buried there. In fact, the prophet is reputed to have graves all around the world.

"In the medieval world, with long distance communication being tenuous, many famous ancient people acquired multiple graves at different locations," says Dr Thomas A Carlson, an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University and author of Christianity in Fifteenth-Century Iraq.

In reality the bones attributed to Nabi Yunus probably belonged to a Christian patriarch named Henanisho I of the Church of the East. He was buried in the monastery in 701.

Archaeologists do not yet know whether Henanisho’s bones survived the explosion. But they have discovered artefacts that have been concealed from human sight for millennia.

Buried under Nabi Yunus is a palace that was both a residence for Late Assyrian kings and a base for the Assyrian army. It dates back to at least the 7th Century BC.

Evidence that there might be a palace beneath Nabi Yunus was found during excavations in the 1850s by two archaeologists, Austen Henry Layard and his Mosul-born assistant Hormuzd Rassam.

Wood engraving of Austen Henry Layard (1851)

After uncovering the ruins of a palace at Kouyunjik on the other side of the river Tigris, Layard and Rassam turned their attention to Nabi Yunus.

The holiness of the site, however, prevented further exploration. The "prejudices of the people of Mosul," wrote Layard bitterly, "forbade any attempt to explore a spot so venerated for its sanctity."

A subsequent excavation conducted by the Iraqi government between 1989 and 1990 did not probe far into the mound for fear of damaging the mosque’s structural foundations. Just like in the 1850s, the imam warned that the shrine could be damaged.

But when east Mosul was liberated from IS in January 2017, archaeologists found something peculiar beneath the rubble of the mosque. There were many more tunnels than had been documented before.

In fact, there were more than 50 new tunnels, some as short as a few metres, others longer than 20.

Dr Peter A Miglus, a professor at the University of Heidelberg who has been conducting preliminary research in the tunnels, described the ground beneath the mosque as being so riddled with holes that it resembled Swiss cheese.

Most of the tunnels appear to have been dug using pickaxes, but there are also traces that suggest a small digger was used. The largest tunnel is around 3.5 metres high and the smallest no more than a metre.

Initial reports suggested that militants had dug these new tunnels themselves. However, residents of east Mosul have told the 91�ȱ� that IS hired locals to do the digging. They wanted to loot the Assyrian artefacts within. The sale of antiquities is thought to have been the group’s second largest source of income after oil.

"It is just like at Mosul museum," says Dr Lamia Al-Gailani Werr, a Research Associate in the Near and Middle East Section at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, referring to IS’s ransacking of antiquities from the museum in 2015.

"It looks like they stole anything they could carry from Nabi Yunus with the aim of selling it on."

The hill beneath Nabi Yunus has been looted carefully, presumably to preserve intact any discoveries. However, there were some finds that appear to have been too big for the militants to take.

These larger items, some of them embedded in the palace walls, could probably not be extracted without threatening the structural integrity of the tunnels dug below the hill.

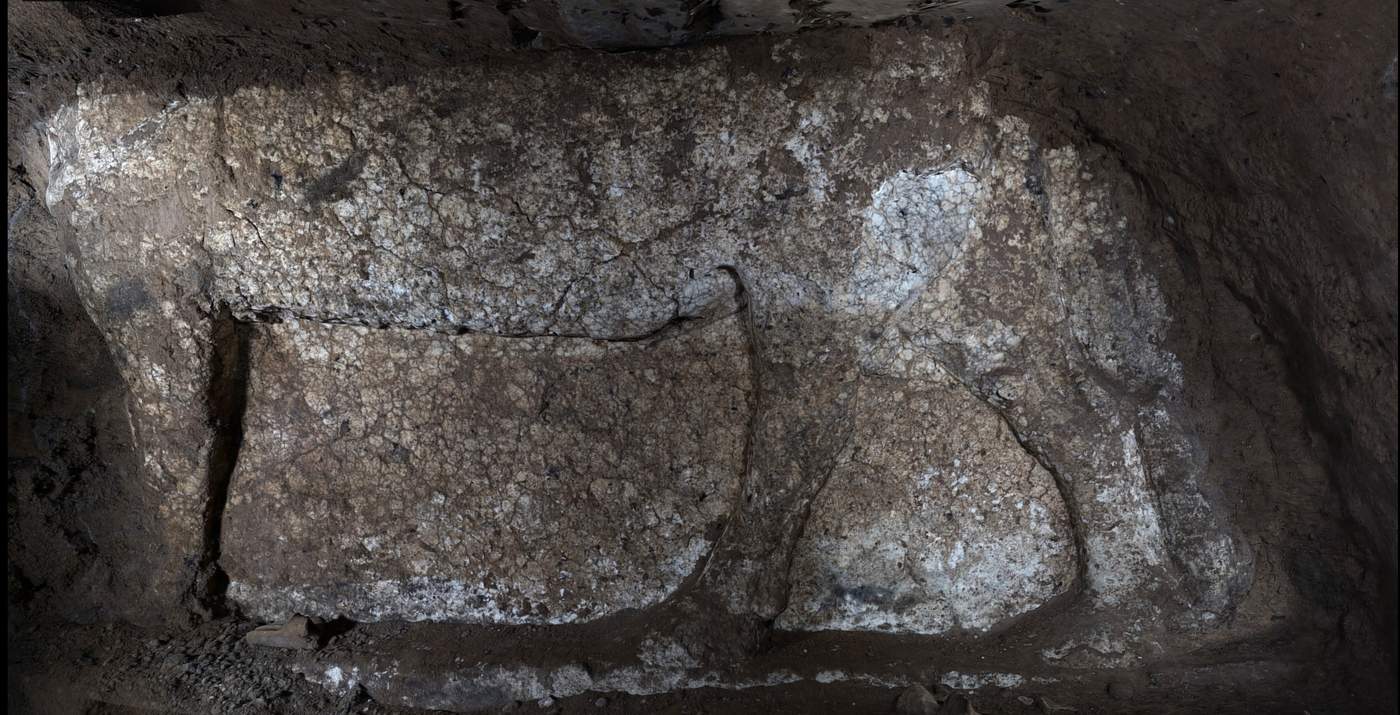

When 91�ȱ� journalists lowered themselves into the dark tunnels beneath Nabi Yunus in March 2018, many of the discoveries made by archaeologists were yet to be removed.

Alongside pieces of limestone and small jars, there were around 30 limestone slabs, bearing the names of the Assyrian kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal. There were also bricks, inscribed with the name of a king called Sennacherib.

But the most astonishing find was a pair of reliefs, each showing a row of women.

It is a discovery that raises more questions than answers.

Dr Paul Collins, the Jaleh Hearn Curator of Ancient Near East at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, believes these images are unprecedented.

"These reliefs have no known parallels elsewhere," he says.

The imagery that has so far been found from Assyrian palaces is overwhelmingly male. Examples include the king spearing a lion and an army returning to the palace after a hunt.

It is very unusual to find female figures of this scale. Women, when portrayed at all, are often captives – the spoils of war – or on a much smaller scale to these reliefs, which are above waist-height.

"Apart from seals and metalwork, we don’t have much Assyrian imagery beyond that of the royal palaces, which tend to focus on military victory," says Dr Collins. "Imagery relating to the religious world – if that is what is meant here – usually shows the gods in relation to the king, and is rare."

What has intrigued experts in Assyrian art is that the women, rather than being depicted in profile as is usual for Assyrian sculpture, are face on.

"It is incredibly exciting to find them," says Dr Amy Gansell, an assistant professor at St John’s University in New York and an expert in ancient Near Eastern art. "It is the first time I have ever seen anything like this."

Although some believe that the repeating, identical design implies that the female figures are goddesses, Dr Gansell thinks it might be otherwise. The absence of horns or a special crown, common symbols used to denote deities in Assyrian art, means they could be depictions of mortal Assyrian women

Dr Gansell believes that the women may represent royal or elite members of society who are portrayed carrying offerings to a god, perhaps in a ritual activity.

"It is much more interesting," Dr Gansell told the 91�ȱ�, "their depiction here means that Nabi Yunus might have had a female worship space. It provides new evidence for the role of women in Assyrian society and religion. It is absolutely unique."

No academic study has yet been done on what the reliefs depict. It is too early to draw substantial conclusions from what has been found in the tunnels, not least because some of the reliefs and inscriptions were found upside down, suggesting that they may have been taken from another place.

The photos taken by the 91�ȱ� Arabic team give the best look yet at the details of these astonishing reliefs.

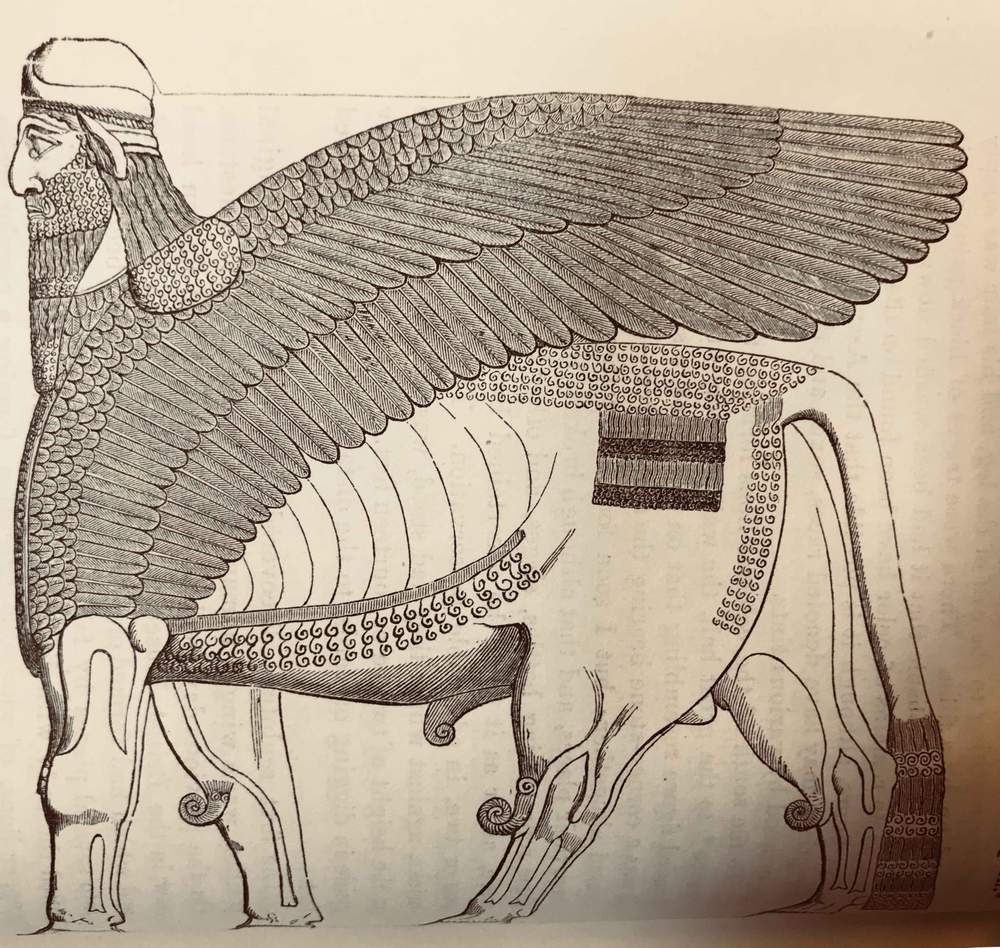

Alongside the reliefs of the women, engravings of a mythical creature called a lamassu have also been discovered in the tunnels. Four stone reliefs of lamassu have been found, as well as the remnants of a fifth.

Enormous stone lamassu were built at the entrance of Assyrian palaces to intimidate enemies and ward off demonic spirits. In the Akkadian language, lamassu means "protective spirit". They have the body of a bull, the wings of an eagle and the head of a human. They stood in pairs with their faces positioned to look toward whoever came through the doorway.

Illustration of a lamassu (circa 1850)

The discovery of lamassu beneath Nabi Yunus shows that there were spaces or rooms that required protection from "evil" or from enemies. It is further proof that the ruins were once an elite royal or sacred place.

In some ways, Islamic State group’s defacement of a lamassu in February 2015 could be seen to echo the sacking of ancient cities like Nineveh. When enemy armies razed cities to the ground, destroying images of the king was an effective way to erase him from history.

But despite their public desecration of the lamassu, IS did not succeed in their aim.

A short distance away in Nabi Yunus, beneath the rubble of Yunus’ tomb, stone reliefs of lamassu remained, untouched, some of them unseen by human eyes for thousands of years.

Their recent discovery stands as a testament to how the story of Nabi Yunus will continue to unfold despite efforts to destroy it.

Alongside the reliefs of the women, engravings of a mythical creature called a lamassu have also been discovered in the tunnels. Four stone reliefs of lamassu have been found, as well as the remnants of a fifth.

Enormous stone lamassu were built at the entrance of Assyrian palaces to intimidate enemies and ward off demonic spirits. In the Akkadian language, lamassu means "protective spirit". They have the body of a bull, the wings of an eagle and the head of a human. They stood in pairs with their faces positioned to look toward whoever came through the doorway.

Illustration of a lamassu (circa 1850)

The discovery of lamassu beneath Nabi Yunus shows that there were spaces or rooms that required protection from "evil" or from enemies. It is further proof that the ruins were once an elite royal or sacred place.

In some ways, Islamic State group’s defacement of a lamassu in February 2015 could be seen to echo the sacking of ancient cities like Nineveh. When enemy armies razed cities to the ground, destroying images of the king was an effective way to erase him from history.

But despite their public desecration of the lamassu, IS did not succeed in their aim.

A short distance away in Nabi Yunus, beneath the rubble of Yunus’ tomb, stone reliefs of lamassu remained, untouched, some of them unseen by human eyes for thousands of years.

Their recent discovery stands as a testament to how the story of Nabi Yunus will continue to unfold despite efforts to destroy it.