When I was eight, my cousin had a baby. My Mum knew I loved babies so she dropped me off at her house for a few days “to help”.

I must have been useful because when another cousin had one, I was dispatched again. I walked the babies up and down the hall and deflected swipes from jealous siblings.

I helped with the bath-and-bed routine for our neighbour. I couldn’t wait to be 12 when I could babysit for all the kids in the village. I couldn’t wait to be a mother myself.

But by 29 I had cervical cancer. The operation I needed to save my life would rob me of my chance to carry a child. I found another operation in a medical paper that would allow me that chance - I found a consultant who could do it. When my referral didn’t come through I just turned up to beg.

Several gruelling years of IVF and miscarriage followed. And then finally, one Thursday morning, the baby I had longed for was wriggling around in my last scheduled ultrasound scan. The midwives waved me off wishing me good luck for the birth.

When I was eight, my cousin had a baby. My Mum knew I loved babies so she dropped me off at her house for a few days “to help”. I must have been useful because when another cousin had one, I was dispatched again. I walked the babies up and down the hall and deflected swipes from jealous siblings. I helped with the bath-and-bed routine for our neighbour. I couldn’t wait to be 12 when I could babysit for all the kids in the village. I couldn’t wait to be a mother myself.

But by 29 I had cervical cancer. The operation I needed to save my life would rob me of my chance to carry a child. I found another operation in a medical paper that would allow me that chance - I found a consultant who could do it. When my referral didn’t come through I just turned up to beg.

Several gruelling years of IVF and miscarriage followed. And then finally, one Thursday morning, the baby I had longed for was wriggling around in my last scheduled ultrasound scan. The midwives waved me off wishing me good luck for the birth.

That afternoon I was at work eating a piece of lemon drizzle cake to mark a colleague’s leaving do when I felt hot gushing liquid soak through my trousers. My waters had broken two months early.

The hospital admitted me and said we had to delay labour for as long as possible, allowing the baby to grow stronger. Ten days later they said we were doing well and could go home the next day. But shortly after midnight, the umbilical cord dropped through me, compressing my baby’s supply of oxygen and nutrients. In the six minutes it took to get to the operating theatre, nurses running and shouting, wheeling my bed through empty corridors, our baby died.

I didn’t sleep for 48 hours. I paced. I refused drugs. My precious longed-for baby was curled and silent in my womb - the cord that had bound us hung from me. When my feet ached from pacing I lay on my side facing Tim, my partner.

I remembered a story of a mother who was told her baby had died, but was born healthy. I rang the buzzer to summon a nurse, I asked if they could have got it wrong. Twenty minutes later my partner rang the same bell, asked the same question.

They gave me a C-section the next morning. As I breathed through the mask and felt the anaesthetic injected into my vein I thought: “I have dreamt of looking into my child’s face for 30 years, and when I wake, I will.”

When she - a baby girl - was given to me, my heart expanded in love. She was beautiful - 30cm tip to toe. She had been dressed in a little white dress and hat, and draped in a white hand-knitted blanket. Her fingers and toes rested neatly in perfection. She was long-limbed like us both. We named her Willow.

I imagined I heard Tim’s heart shatter when he said her name. I looked at her in wonder. I couldn’t understand why she was dead.

The midwives and doctors came. There were no answers to our questions. Maybe they weren’t the right questions. We were at the edge of the delivery wing, and I had to listen to women in labour and to the mewling newborns.

My arms ached. I thought I had a blood clot, but the doctors told me it was normal - a biological response to the shock that there was no living child for me to hold. I sobbed. My milk came through, marking my T-shirt, and I was too exhausted to be embarrassed.

That afternoon I was at work eating a piece of lemon drizzle cake to mark a colleague’s leaving do when I felt hot gushing liquid soak through my trousers. My waters had broken two months early.

The hospital admitted me and said we had to delay labour for as long as possible, allowing the baby to grow stronger. Ten days later they said we were doing well and could go home the next day. But shortly after midnight, the umbilical cord dropped through me, compressing my baby’s supply of oxygen and nutrients. In the six minutes it took to get to the operating theatre, nurses running and shouting, wheeling my bed through empty corridors, our baby died.

I didn’t sleep for 48 hours. I paced. I refused drugs. My precious longed-for baby was curled and silent in my womb; the cord that had bound us hung from me. When my feet ached from pacing I lay on my side facing Tim, my partner.

I remembered a story of a mother who was told her baby had died, but was born healthy. I rang the buzzer to summon a nurse, I asked if they could have got it wrong. Twenty minutes later my partner rang the same bell, asked the same question.

They gave me a C-section the next morning. As I breathed through the mask and felt the anaesthetic injected into my vein I thought: “I have dreamt of looking into my child’s face for 30 years, and when I wake, I will.”

When she - a baby girl - was given to me, my heart expanded in love. She was beautiful - 30cm tip to toe. She had been dressed in a little white dress and hat, and draped in a white hand-knitted blanket. Her fingers and toes rested neatly in perfection. She was long-limbed like us both. We named her Willow.

I imagined I heard Tim’s heart shatter when he said her name. I looked at her in wonder. I couldn’t understand why she was dead.

The midwives and doctors came. There were no answers to our questions. Maybe they weren’t the right questions. We were at the edge of the delivery wing, and I had to listen to women in labour and to the mewling newborns.

My arms ached. I thought I had a blood clot, but the doctors told me it was normal - a biological response to the shock that there was no living child for me to hold. I sobbed. My milk came through, marking my T-shirt, and I was too exhausted to be embarrassed.

In the bereavement suite there was a kitchen, to make cups of tea I couldn’t imagine any bereaved parent could ever stomach. I found myself looking at the cleaning rota - such a stark reminder of the other families who had been there. I thought of their loss. I focused on their survival.

Stillbirth is much more common than people might think but it’s rarely talked about because pregnancy is a time of joy and hope.

We stayed another four nights, our daughter in a refrigerated cot. No-one ever suggested we left but I knew when it was time. I couldn’t bring myself to say goodbye to the midwives who sat with us through that night, who dressed our daughter for us. There were no words of thanks big enough, so they just cried, and we cried, and nodded our heads and left.

We had two matching cuddly lambs in hospital - one that we slept with, one for Willow in her crib. On the drive home I clutched our lamb, damp with tears. I whispered words to it and imagined my daughter could hear them.

Grief folded and stretched time. The midwives had reminded us we were legally required to register Willow’s birth. So one day we travelled to a register office and an official asked quiet sad questions. We left holding legal proof she was here, she was real. Birth and death shared the paper, the only document she will ever have.

Post piled up and I looked away from it, from other people’s kindness and awkwardness. Some friends came. Some family. I put my maternity jeans back on and exchanged platitudes, but there was nothing anyone could say so I went back to bed. We planned a funeral in place of a christening.

Dry-eyed (there seemed to be nothing left), I delivered a eulogy to a crematorium filled with weeping family. The flowers were too big for the little lid of Willow’s casket. We asked them not to close the curtains at the end. When I finally managed to leave I carved off part of my soul to stay with her, my first child.

In the bereavement suite there was a kitchen, to make cups of tea I couldn’t imagine any bereaved parent could ever stomach. I found myself looking at the cleaning rota - such a stark reminder of the other families who had been there. I thought of their loss. I focused on their survival.

Stillbirth is much more common than people might think but it’s rarely talked about because pregnancy is a time of joy and hope.

We stayed another four nights, our daughter in a refrigerated cot. No-one ever suggested we left but I knew when it was time. I couldn’t bring myself to say goodbye to the midwives who sat with us through that night, who dressed our daughter for us. There were no words of thanks big enough, so they just cried, and we cried, and nodded our heads and left.

We had two matching cuddly lambs in hospital - one that we slept with, one for Willow in her crib. On the drive home I clutched our lamb, damp with tears. I whispered words to it and imagined my daughter could hear them.

Grief folded and stretched time. The midwives had reminded us we were legally required to register Willow’s birth. So one day we travelled to a register office and an official asked quiet sad questions. We left holding legal proof she was here, she was real. Birth and death shared the paper, the only document she will ever have.

Post piled up and I looked away from it, from other people’s kindness and awkwardness. Some friends came. Some family. I put my maternity jeans back on and exchanged platitudes, but there was nothing anyone could say so I went back to bed. We planned a funeral in place of a christening.

Dry-eyed (there seemed to be nothing left), I delivered a eulogy to a crematorium filled with weeping family. The flowers were too big for the little lid of Willow’s casket. We asked them not to close the curtains at the end. When I finally managed to leave I carved off part of my soul to stay with her, my first child.

Two weeks later Tim returned to the sanctuary of work and I was left alone in the house. Our grief took different paths, and my loneliness and isolation increased. I scared myself reading about the rates of relationship breakdown after the death of a child, and decided to find a bereavement counsellor. I found a lot of help on offer for mothers, very little for fathers, but eventually found someone who would help us together, and whom we still see now.

My period came and I raged at the betrayal of my body. I deleted friends on Facebook who had healthy babies the same age as Willow, or friends pregnant with a second or third child. The algorithms made social media a dark place for me, with adverts for baby food, prams and clothes flooding my feed. I became angry, bitter and withdrawn.

One day I took three trains to a house in the far north-east corner of England to visit my 103-year-old grandmother, Nancy. I let myself in and sat at her feet, my head in her lap. She herself had a stillborn baby more than 60 years ago. She stroked my hair and said she was “sorry about the baby” - the baby she didn’t know we originally planned to name after her. It was the hardest visit I made and yet somehow it was the start of my healing.

I did a lot of sleuthing. I applied for my notes from all the hospitals I’ve been treated in over the last decade and researched every stage of my medical treatment and pregnancy, cross-referencing and breaking the codes of doctors’ scribbles. At the heart of my obsession was guilt, a fear that somehow the stillbirth was my fault. A fear that was wrong, but that other parents of stillborn babies seem to feel too.

I found a nine-week-old puppy and brought her home. She weighed 2kg, the weight of a newborn. Her needs made me feel useful. During night-time toilet trips we stood shivering in the dark, and she jumped at me like a child wanting to be picked up. When I called across the park for her, I occasionally called her Willow.

Christmas loomed but I averted my eyes, hastily shoving money into cards for nieces and nephews. We escaped the dreams of our first family Christmas by hiring a remote shepherd’s hut in Suffolk. We walked miles every day, taking it in turns to carry our puppy. On Christmas Eve I went to a magical midnight Mass in a small rural church. I cried silently throughout the service. The old lady next to me, a stranger, reached out to hold my hand.

Two weeks later Tim returned to the sanctuary of work and I was left alone in the house. Our grief took different paths, and my loneliness and isolation increased. I scared myself reading about the rates of relationship breakdown after the death of a child, and decided to find a bereavement counsellor. I found a lot of help on offer for mothers, very little for fathers, but eventually found someone who would help us together, and whom we still see now.

My period came and I raged at the betrayal of my body. I deleted friends on Facebook who had healthy babies the same age as Willow, or friends pregnant with a second or third child. The algorithms made social media a dark place for me, with adverts for baby food, prams and clothes flooding my feed. I became angry, bitter and withdrawn.

One day I took three trains to a house in the far north-east corner of England to visit my 103-year-old grandmother, Nancy. I let myself in and sat at her feet, my head in her lap. She herself had a stillborn baby more than 60 years ago. She stroked my hair and said she was ‘sorry about the baby’ - the baby she didn’t know we originally planned to name after her. It was the hardest visit I made and yet somehow it was the start of my healing.

I did a lot of sleuthing. I applied for my notes from all the hospitals I’ve been treated in over the last decade and researched every stage of my medical treatment and pregnancy, cross-referencing and breaking the codes of doctors’ scribbles. At the heart of my obsession was guilt, a fear that somehow the stillbirth was my fault. A fear that was wrong, but that other parents of stillborn babies seem to feel too.

I found a nine-week-old puppy and brought her home. She weighed 2kg, the weight of a newborn. Her needs made me feel useful. During night-time toilet trips we stood shivering in the dark, and she jumped at me like a child wanting to be picked up. When I called across the park for her, I occasionally called her Willow.

Christmas loomed but I averted my eyes, hastily shoving money into cards for nieces and nephews. We escaped the dreams of our first family Christmas by hiring a remote shepherd’s hut in Suffolk. We walked miles every day, taking it in turns to carry our puppy. On Christmas Eve I went to a magical midnight Mass in a small rural church. I cried silently throughout the service. The old lady next to me, a stranger, reached out to hold my hand.

A stillborn baby provides the mother with the same rights and protection as a newborn baby, and as I was entitled to maternity leave, I took it, returning after four months. Work was an easier place than home. I could hide from my loss. And so good did I become at compartmentalising that I was occasionally surprised by colleagues asking if I had had a boy or a girl. I got used to replying “my daughter was stillborn”, and then patting them on the arm and saying “it’s OK, please don’t worry”.

In the long evenings at home I drank too much red wine. I watched Modern Family on a loop. But throughout the winter, there were glimmers of hope, like the snowdrops bravely poking their heads up. Some days I could feel positive again, some days I could see my friends and laugh. Sometimes I was ready to smile when Tim opened the front door. Many times I think we both just tried, not for ourselves, but for each other.

My coping mechanisms are all about doing stuff and so I planned a part of our garden to dedicate to Willow, buying graph paper and poring over garden design books. We started landscaping in the coldest wettest week in February. We hired a 1.5 tonne digger. Friends and family came to help us in snow and frost, in driving rain, forking through piles of wet soil and stones to remove weeds.

Our joyful little puppy Pina played in the mud at our feet and then stamped paw prints all over the kitchen floor. I found an artist to make a sculpture out of willow branches. We visited favourite beaches to collect stones to pave the path. We exhausted ourselves with manual work.

In the week leading up to Mother’s Day, I stood watching the children leave the local village school. On the day itself, I opened the door to the nursery for the first time. I unfolded and refolded the babygros, and then lay down on the floor with the last one, placing it between my collar bone and navel. The dust motes floated in the afternoon sunlight. I thought of the email telling me the curtains for the nursery were waiting. When I had replied that we no longer needed them, they had simply written back: “We will send when you are ready.” I wondered if the saleswoman herself had lost a baby.

I cried and cried and eventually fell asleep. When I woke up it was dark. I found two Mother’s Day cards. One from my Mum, the other from Tim, saying that I was and will always be a brilliant mother to Willow. From that day on, I left the nursery door open, and the air now circulates better through our house.

We prepared for Willow’s first birthday by planning a party in her garden to raise funds for stillborn charities. One of the charities we want to help provides memory boxes to hospitals for bereaved parents. We were given one for Willow and I found the courage to look at it again.

A stillborn baby provides the mother with the same rights and protection as a newborn baby, and as I was entitled to maternity leave, I took it, returning after four months. Work was an easier place than home. I could hide from my loss. And so good did I become at compartmentalising that I was occasionally surprised by colleagues asking if I had had a boy or a girl. I got used to replying “my daughter was stillborn”, and then patting them on the arm and saying “it’s OK, please don’t worry”.

In the long evenings at home I drank too much red wine. I watched Modern Family on a loop. But throughout the winter, there were glimmers of hope, like the snowdrops bravely poking their heads up. Some days I could feel positive again, some days I could see my friends and laugh. Sometimes I was ready to smile when Tim opened the front door. Many times I think we both just tried, not for ourselves, but for each other.

My coping mechanisms are all about doing stuff and so I planned a part of our garden to dedicate to Willow, buying graph paper and poring over garden design books. We started landscaping in the coldest wettest week in February. We hired a 1.5 tonne digger. Friends and family came to help us in snow and frost, in driving rain, forking through piles of wet soil and stones to remove weeds.

Our joyful little puppy Pina played in the mud at our feet and then stamped paw prints all over the kitchen floor. I found an artist to make a sculpture out of willow branches. We visited favourite beaches to collect stones to pave the path. We exhausted ourselves with manual work.

In the week leading up to Mother’s Day, I stood watching the children leave the local village school. On the day itself, I opened the door to the nursery for the first time. I unfolded and refolded the babygros, and then lay down on the floor with the last one, placing it between my collar bone and navel. The dust motes floated in the afternoon sunlight. I thought of the email telling me the curtains for the nursery were waiting. When I had replied that we no longer needed them, they had simply written back: “We will send when you are ready.” I wondered if the saleswoman herself had lost a baby.

I cried and cried and eventually fell asleep. When I woke up it was dark. I found two Mother’s Day cards. One from my Mum, the other from Tim, saying that I was and will always be a brilliant mother to Willow. From that day on, I left the nursery door open, and the air now circulates better through our house.

We prepared for Willow’s first birthday by planning a party in her garden to raise funds for stillborn charities. One of the charities we want to help provides memory boxes to hospitals for bereaved parents. We were given one for Willow and I found the courage to look at it again.

Val Isherwood runs the Tigerlily Trust, which provides hospitals with blankets, wraps and gowns for stillborn babies

Everything went great with my pregnancy until probably 16 or 17 weeks. We got that phone call that started with: “Are you on your own?” The hospital told me my baby had something called Edwards’ syndrome and not to expect her to live past 28 weeks.

She got to 32 weeks, and then I was getting something out of one of the bureau drawers in the lounge and felt a stab of pain. We went into hospital and her heartbeat had stopped.

Even though we tried to prepare for that moment I can't really remember much about that day. I remember them saying they would give me this tablet and I'd go home and come back the next morning.

I went through this phase later on where I thought: ‘Was I ever pregnant?’

I suddenly felt very scared that I had a dead body inside me and how cruel it was to send me home. But I'm so glad for that time, because it gave us that last night together. And come Tuesday morning I didn’t want to go back into hospital. I just wanted to keep her forever safe inside and felt like no-one should take her from me.

But that time in hospital was just beautiful. Friends came and met Lily which was really important, because I went through this phase later on where I thought: “Was I ever pregnant?”

I'd bought clothes for her early on in the pregnancy, and they were far too big, so we didn't have anything to put her in, and the hospital didn't offer us anything. So when I was in early labour we went out into town and the only thing we could find was a little T-shirt, and my Mum sewed it in the hospital into a little dress.

One of my regrets is that the dress was cremated with her - I really wish that I still had what she'd been wearing. That's why now we give outfits in matching pairs so that parents can keep the one the baby has worn.

We tried to have another baby as soon as we could after Lily, and we did think about IVF, but with my age the odds were stacked against me. I was 46 at the time and I didn't think I could go through all that and it not work out. So I thought a lot about acceptance - my message to myself was if it's not meant to be then that's my story. I knew I needed to find positive ways to channel all that love and energy that would have gone into raising Lily.

Everything to do with the Tigerlily Trust is inspired by what I wish had been there for me.

So I started appealing for knitters who would help us create the clothes I wished I had been given. People then asked if they could donate their wedding dresses to turn into little gowns, so we've got a lovely seamstress on the Isle of Man who makes them.

Some of the women who had a stillborn baby before we existed were just told to go and buy a doll's dress which they felt was so insulting. Now a lot of the parents who get in touch can't believe someone has gone to those lengths to knit something to put their baby in and to give them that dignity.

I have about 380 names on my list of people who have contributed in some way. Some of them are grandmas whose daughters have lost babies.

My advice to other parents going through this is let yourself grieve hard. Don't be afraid of your grief - share it with people. That's almost precious time before the world sort of expects you to be OK. Let yourself have that time.

Rachel Hayden runs Gifts of Remembrance, which trains midwives to take photos of stillborn babies - this section contains an image of her son Rowan who was stillborn

Rowan was one of triplets, which was a bit of a surprise to me at 40 with two kids already. But the interesting thing is that when I found out I was pregnant I got a sense of him, so I felt like I already knew who he was.

I went in for a scan at 31 weeks and they discovered there was no heartbeat for him. It’s a moment which I’m sure all parents of stillborn babies relate to. There’s just that stillness on the monitor.

We can end up grieving not only for the fact our babies died, but... for the fact we never saw them

I remember the way the nursery nurse spoke to him and handled him and it made me feel I could do the same. So it was “hello and what’s your name?” and “I bet your Mum wants to give you a cuddle”, and all this was great for me because I was utterly clueless.

But I didn’t even think to ask to be involved in the memory making.

She took him away and took handprints and footprints and dressed him and lay him in his Moses basket, and then took two photos of him lying there.

I didn’t know what he really looked like naked or what he was wearing under his little knitted gown, and she took no photographs of him being held - he looked so alone.

Although I was remarkably grateful for what I had, I later came across the work of Todd Hochberg, an amazing US photographer, and realised I could have had so much more. Not only was I blown away by the photographs and how emotional they were, but it was the stories they told - and I found myself comparing.

What I say to the midwives in the training is you need to think for the future, and guide the parents through a process of gathering up details and stories, and saying: “This may feel too much now but it's going to be important later.”

Very little of my training is actually about taking photographs - a big chunk of it is about midwives empowering parents, and saying the right things, and giving them time.

I'll talk about how you have photographs that you might share with people, but there are plenty of photographs that just help you remember - every single photograph is going to be of importance to the family.

This is actually a therapeutic intervention you are doing to help families make sense of what's happened. You're saying: “This is what happened to you in all its mess.” Midwives and nurses clean things all the time but I say just hand over everything as it is. The most precious thing to me of Rowan's is his hat because it smelt like him, so we challenge that approach.

A photo of Rachel's baby, Rowan

If you try and protect us then we can end up grieving not only for the fact our babies died, but we can be grieving for the fact we never saw them. A really poignant story was a mum who said she had never seen her baby girl’s bottom - she said that her other children had birthmarks on their bottoms and she never knew if she had one.

When we look back on things there'll be moments that we will even identify in terms of joy, because you're saying hello to your baby, as well as goodbye.

Ruth Rodgers used to work in finance but was inspired to retrain as a midwife after the stillbirth of her daughter Scarlett. She has just started her first posting, having qualified this summer.

Scarlett was born in November 2011 when I was 31 weeks pregnant. I realised she wasn’t moving so much, but I wasn’t really that worried - I did a full day of work before I went to the hospital. And they couldn't find a heartbeat pretty much straightaway.

I had this amazing bereavement midwife, Jane, who I spoke to on the phone. During the two days before I went into labour she told me not to worry about things like funeral arrangements and post-mortems, but just to think about how I wanted to spend time with my little girl - helping me focus on the most important things at the right times.

There's some amazing care out there, but there are also some poor things that happen repeatedly that are so easy to fix

I also had a brilliant labour ward midwife. It's funny the things that you worry about - I assumed that she would have rigor mortis. I was frightened about how I might feel when I saw her.

And she said: “She'll just look like a baby. She'll be a bit small, her skin might be quite thin, and she'll probably not have her eyes open, but otherwise she'll just look like your baby.” That was all I needed to hear to just carry on.

Of course there were moments of utter misery, but I also have strangely fond memories of watching Strictly Come Dancing and the X Factor, and eating lasagne with one hand and holding the gas and air with the other!

She was born just before six in the morning, and I remember thinking it was amazing that she was still warm and I needed to remember the way that felt because she wouldn’t stay like that.

I fell pregnant again seven weeks after I'd had Scarlett, and miscarried again, having miscarried before. And that's when I became really obsessed with how having a baby works, with how all the embryology works. I read textbooks, I read research papers, I emailed professors in recurrent miscarriage - that's the way I approach life.

I had another two miscarriages after that, and throughout it all Jane was basically there the whole time and we developed a really special relationship. I guess that’s really where the idea of me training to become a midwife myself started - that supportive relationship between a woman and her midwife.

I was lucky enough to go on to have two beautiful boys, one just before I started training, and one in the middle of my degree. The first of these was an incredibly anxious pregnancy, and I received the most fantastic care from Jane, my consultants and my community midwife, all of whom knew my history and understood the way I felt. I could not have got through it without them, without suffering significant mental health consequences.

In my third year of training I did a long stint on a labour ward and there was a lady who came in thinking she was in labour, only to find her baby had died. It was incredibly fulfilling to care for that woman and her baby and help her through everything.

I think it's rarely appropriate to talk about your own experience to somebody else. If a woman specifically asked me if I’d had a stillbirth then I’d tell them, but I would never volunteer that, because the moment then would become about me and not about them.

But I do suggest things that I found helpful, or that I know others did. I've met so many people over the last few years through online groups who've dealt with their grief and the process of having a subsequent baby all very differently. How you deal with having a stillbirth is incredibly personal.

There's some amazing care out there, but there are also some poor things that happen repeatedly that are so easy to fix. The classic ones are not reading the mum’s notes before an appointment, or not calling the baby who died by their name.

The research very clearly says that grief isn't necessarily related to gestation - there is a link, but actually the link is more to do with the “assignment of personhood”. If you have assigned a person to the baby inside you, you have created a relationship with that person that means that you feel the grief more acutely when they're gone.

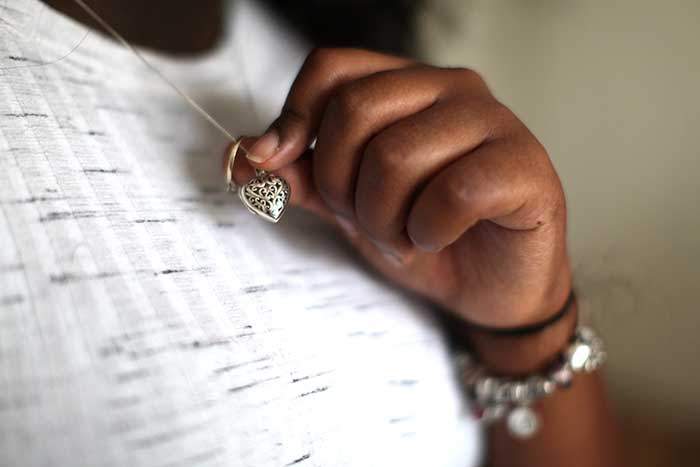

Publishing graduate Aliyah makes bespoke wall prints through her online shop, which help parents celebrate their baby’s name and birth date and is working on a bespoke memory book. She is expecting another baby at the end of October.

One of the hardest parts is that we had bought everything for Aamiya - we had loads of clothes ready, we had her cot set up in the bedroom, everything was washed and ready for her.

I had swelling but they just told me it was normal pregnancy swelling. Because I didn’t have any other symptoms I don’t think anyone was overly concerned. And then I woke up one morning and I didn’t feel anything and I just thought I should go and get checked out. And that’s when they told us she’d passed away and I found out I had pre-eclampsia.

They told me my blood pressure was really high and there was lots of protein in my urine and they rushed me into delivery really fast.

I must have fallen asleep because when I woke up she was already bathed and dressed, and next to me in the refrigerated cot. And that’s one thing I regret - obviously it wasn’t in my control to stay awake, but I feel like I missed out on dressing her and that time after birth - the little things you always imagined doing for your baby.

There’s that awkward moment when people don’t know what to say or do, but with my friends it was OK because they all know me so well, and they made the effort to come round and bring me flowers and chocolates. It was nice to know people cared, even if I didn’t want to speak or do anything.

I’ve always been creative, and I first started with the memory book which I’m making for Aamiya. And then I found out about the baby loss community on Instagram.

I got talking to a lot of mums from all over - from America, Canada - just sharing stuff that I’d done in my day and projects that I was working on. And then quite a few people started asking if I could make something for their babies too.

At some point after Aamiya was born I had this overwhelming feeling of wanting everything in the house to reflect her - for everyone to remember she was here. And I think that was a way of dealing with grief - creating stuff so I could put her around the house.

You can spend hours designing things and it just takes your mind off things.

There have been times when I’ve thought it isn’t healthy to just be consumed by one moment in time, so I’ve put the memory book project off for a bit and focused on getting back to work and seeing friends more, but there are times when I go back to it.

I’m definitely more anxious about being pregnant again since I hit the 30-week mark.

At the beginning of my pregnancy, while I was happy and felt blessed that I was able to conceive another child, there were definitely feelings of guilt as you don't want your angel baby thinking they will be forgotten, because they never will be - my partner and I think about Aamiya every single day.

However, as time has gone on these feelings of guilt have subsided - I truly believe this baby was sent by Aamiya. It's been a good pregnancy. Anxiety does get the better of me at times but I try and remain positive. My partner and I will make sure this baby grows up knowing all about their big sister Aamiya.

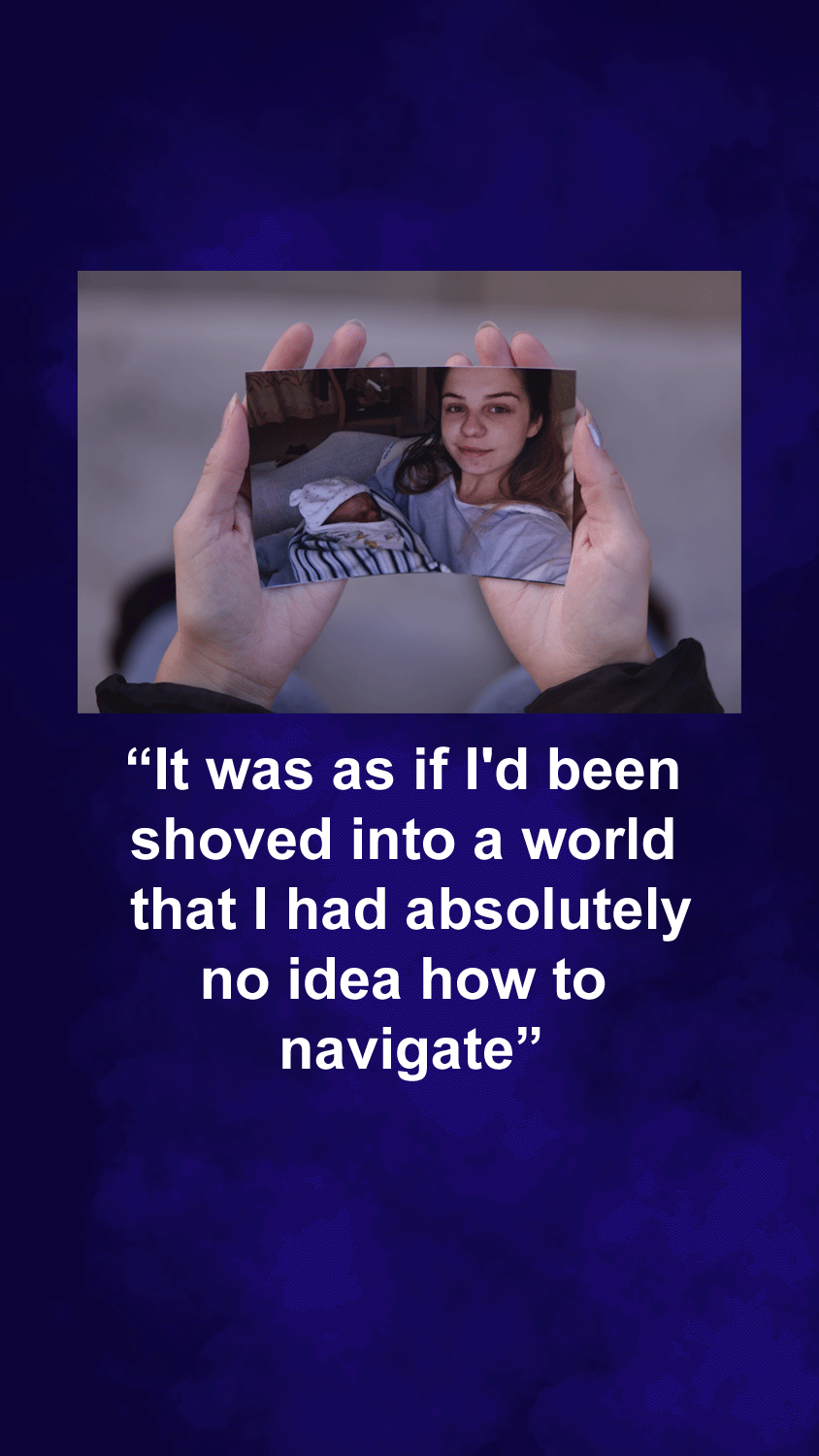

Megan Evans began a vlog about stillbirth just weeks after the death of her son Milo - this section contains images of him

Before Milo I thought I wasn't maternal - I've got two older brothers who wound me up about pregnancy and how painful childbirth was, so I always said I'm not having children.

When the pregnancy test came back positive, I just thought I'm not supposed to have children.

Because I was so young and petrified, I went straight on to YouTube and typed in “19 and pregnant” but there wasn't much there. There were a few videos but they were by 19-year-olds who had money. I needed to see someone who was just normal and working class, so the next day I told my Mum I was just going to start vlogging about my own situation.

As soon as I started making those videos I had women getting in touch saying they felt the same - how they didn't have their own house and a stable financial situation either. So the vlog all started from there, and I really enjoyed having people get in touch saying “me too” which made me feel comfortable with my situation.

And as time went on then everything just fitted into place.

It's funny how your maternal instincts just kick in and you wouldn't imagine it any other way.

One day I realised that I hadn't felt Milo move all day, and I thought I'd better get checked just in case.

The midwife started to monitor me and she couldn’t find a heartbeat. And the sonographer came in, but so did a midwife, a nurse, a doctor, a consultant. So it was a whole string of people standing at the end of my bed and that's when I really clocked that something was wrong.

It was as if I'd been shoved into a world that I had absolutely no idea how to navigate.

The next day I spent all day seeing my family and discovered my Nan had had a son who died a few days after he was born. I asked her how I was going to survive it and she said: “Take lots of pictures, and make the most of the time you have with him.”

When I went into hospital to be induced I was very scared about what he was going to look like, so I asked my Mum to see him first. She said “oh my god, he’s just perfect” and showed him to me. It was the moment I realised that was the baby I’d been carrying for eight months. Death doesn’t change anything - this was the first time I was going to meet my son.

But it was also devastating. I was holding everything that I was waiting for but I knew I would have to give my baby back. My future was being erased before my eyes.

I said to one of the midwives: “I feel like I'm the only person in the world this is happening to.” She replied: “It's just one of those things that nobody speaks about.”

Three days after I came out of hospital I started thinking about my vlog. People were still commenting on my previous videos saying “wow I'm pregnant too”.

Again I looked for vlogs about stillbirth and again I couldn’t find what I was looking for.

I wasn’t expecting so many people to watch the videos because I didn’t realise how common stillbirth is.

It helped me by telling his story but it was also comforting to see other people say his name.

If someone you know experiences a stillbirth you don't need to know the right things to say. You just need to acknowledge their pain, acknowledge their grief, understand that you're not going to understand, and let them talk and talk until they've finished.

As time's gone on, I've met a lot of people who've understood, and I've found my feet in grief which helps a lot.

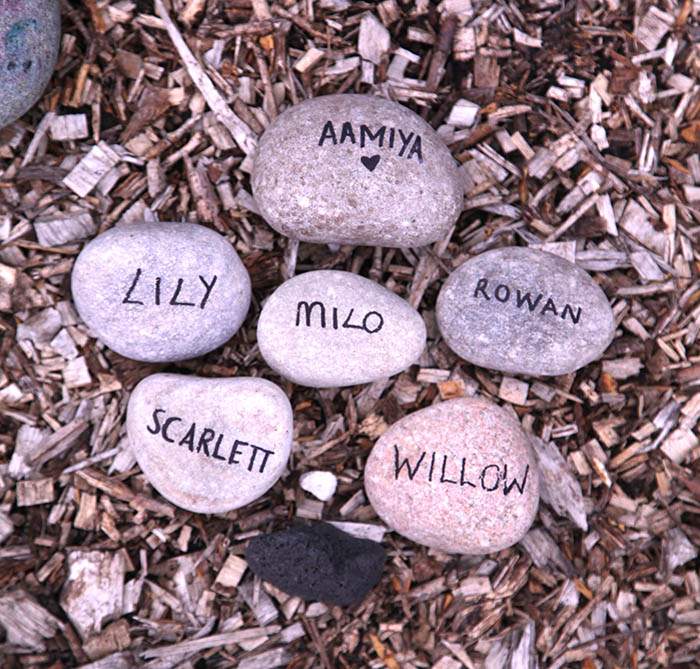

Rowan, Scarlett, Aamiya, Lily, Milo, and Willow. As I lay stones in their memory in a special baby loss garden in Staffordshire, I realise that even though they didn’t see the world, they have changed it through the action they have inspired in their mothers.

But I also know that for each of these women there are many more who choose to hold their memories privately, who mourn behind closed doors.

One in 225 pregnancies in the UK will end in stillbirth. And the death of a baby will not just affect the parents, but the grandparents, the siblings, the family and friends. A bereaved mother, in the process of getting physical care, gets emotional care throughout, but this risks men feeling sidelined, and powerless to help.

The parents I speak to agree that the taboo and silence around stillbirth seems to be gradually easing, but there are still many people who have simply never spoken to me about Willow, never said her name.

My arms no longer ache like those first hours, but they are still empty - I am a mother without a baby

I have, though, felt support from so many people, especially women, many of whom I’d never even met before. As a journalist I have specialised in women’s stories around the world for many years, and yet only this has made me feel an invisible solidarity, a wall of history, of empathy, of strength from women around me.

Over the past year my need to remember and memorialise Willow has jostled with my need for self-preservation. A year on, grief can still occasionally floor me, slicing behind my knees, but I can feel it coming and I can prepare, knowing I can survive its brief but powerful kick.

Willow’s birth made me a Mum and Tim a Dad. My arms no longer ache like those first hours, but they are still empty. I am a mother without a baby.

I think about my own mother. For weeks she sat in our house, the horrific shadow of bereavement hanging over us, my hacking sobs punctuated by the clack of her knitting needles.

She made a beautiful pure white blanket for a baby box which will be opened at a time of immense loss. She knitted it for a stranger who at the time of knitting was an excited expectant mother-to-be, but whose baby would come too early, too sick, or simply stillborn for no known reason.

That baby - we will never know his or her name - will be rocked and mourned in their parents’ arms and will also, thanks to my Mum, have an extra layer, wrapped also in my family’s love - our endurance and our hope.