It was 1 April 2018 - Easter weekend - and Xu Yanjun was amid the bustling bars and restaurants in the Sainte Catherine district of Brussels, not far from the Grand Place.

He had flown into Amsterdam and then driven into Belgium for the first part of his European holiday.

But he was no tourist, according to the US authorities.

Place Sainte-Catherine, Brussels

Xu had allegedly come to meet an American employee of GE Aviation - a specialist on aircraft engine design. The company had spent decades and millions of dollars developing composite materials which allowed lighter, sturdier and cheaper fan blades and cases inside engines.

Xu was expecting the American to hand over secrets, according to a US indictment. That was because, the US authorities allege, Xu was a spy for the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS).

But he was in for a surprise.

Rather than an American contact, he was greeted by Belgian police, acting on an international arrest warrant issued by the FBI.

Xu Yanjun, shortly after his arrest

Xu’s alleged plot to steal secrets began in March 2017. An American employee of GE Aviation, which supplies engines for both commercial airliners and the military, received an email from someone at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronomic (NUAA), according to Xu’s US indictment.

Would the engineer like to come for “an exchange” to China? His travel expenses would be paid.

In February 2018, the engineer sent over a presentation. On the first page was a company logo and a warning that the contents belonged to GE and were confidential. Xu allegedly continued to send questions.

There is a telling exchange of messages in the indictment. The engineer said the requests involved commercial secrets. Xu said they could discuss this in person. He said the engineer should copy a file directory from his company computer.

But the file directory had been doctored to remove sensitive information.

By this time, GE Aviation had discovered what was going on. The engineer - who has not been charged - was co-operating with GE and law enforcement.

Xu did not know his supposed contact was working against him. He allegedly wanted a hard drive full of data to be brought to a meeting in Europe. “If we are going to do business together, this won’t be the last time, right?” he said.

On 1 April Xu was in Belgium and the net closed tight.

The US claims his job was to obtain technical information from aviation and aerospace companies in the US and Europe.

According to the indictment, since 2013 he had been working with Chinese universities and institutions to identify and target specific engineers with the secrets China needed, passing on the data to government, academia and companies. Xu’s American lawyer declined to comment, but the Chinese Foreign Ministry is reported as saying the case was a “pure fabrication”.

Xu is alleged to have worked with individuals at NUAA, a university linked to the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. It is one of the top engineering universities in China and collaborates with Chinese aircraft manufacturers.

NUAA confirmed that Xu was a part-time postgraduate student, but echoed the Foreign Ministry dismissal of the allegations. “Our school is the contributor and legal user of intellectual property. We’ve always respected and safeguarded intellectual property and never support intellectual property theft.”

The National University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (NUAA), Nanjing

In April 2014, Xu discussed plans to get hold of materials related to a military aerial refuelling aircraft, the indictment alleges. He is also alleged to have sent documents to a contact thought to be associated with a Chinese company involved in making engine parts. An engineer from another company sent a paper on drone technology to Xu who allegedly forwarded it to the NUAA.

Xu spent six months in custody before being extradited to the US. He was charged with conspiring and attempting to commit economic espionage and theft of trade secrets. The trial is likely to happen next year. Xu denies any wrongdoing.

“The impact to GE Aviation is minimal thanks to early detection, our advanced systems and internal processes, and our partnership with law enforcement," the company said in a statement.

Xu’s case is an unprecedented act - the extradition of an alleged intelligence officer for economic espionage. But it is being seen as part of an increasing campaign by Washington to confront China.

The US says Xu’s case is emblematic of China’s plan - intelligence officials working hand-in-glove with Chinese companies to steal technical secrets from the West and then use them to advance their own economy.

“From a perspective of threat against United States national security and our interests, [the] Chinese is number one by far,” says Bill Evanina, a former FBI official who is now director of the US National Counterintelligence and Security Center which co-ordinates the defence of America against foreign spies.

Bill Evanina: “From a perspective of threat against United States national security and our interests, Chinese is number one by far”

Xu’s case is not the only one to involve aviation. In another case revealed just weeks after, a group of intelligence officers and hackers were charged. They were also alleged to be linked to the Jiangsu branch of the MSS.

In this case, dealing with events from November 2013, a Chinese spy is alleged to have met the Chinese employee of a French aerospace company with an office in Suzhou.

“I’ll bring the horse to you tonight,” the spy had communicated in advance, according to the detailed US indictment, suggesting they should pretend to bump into each other at a restaurant. “This way we don’t need to meet in Shanghai.”

The horse was code for Trojan horse malware which was to be used to infect the company’s computers.

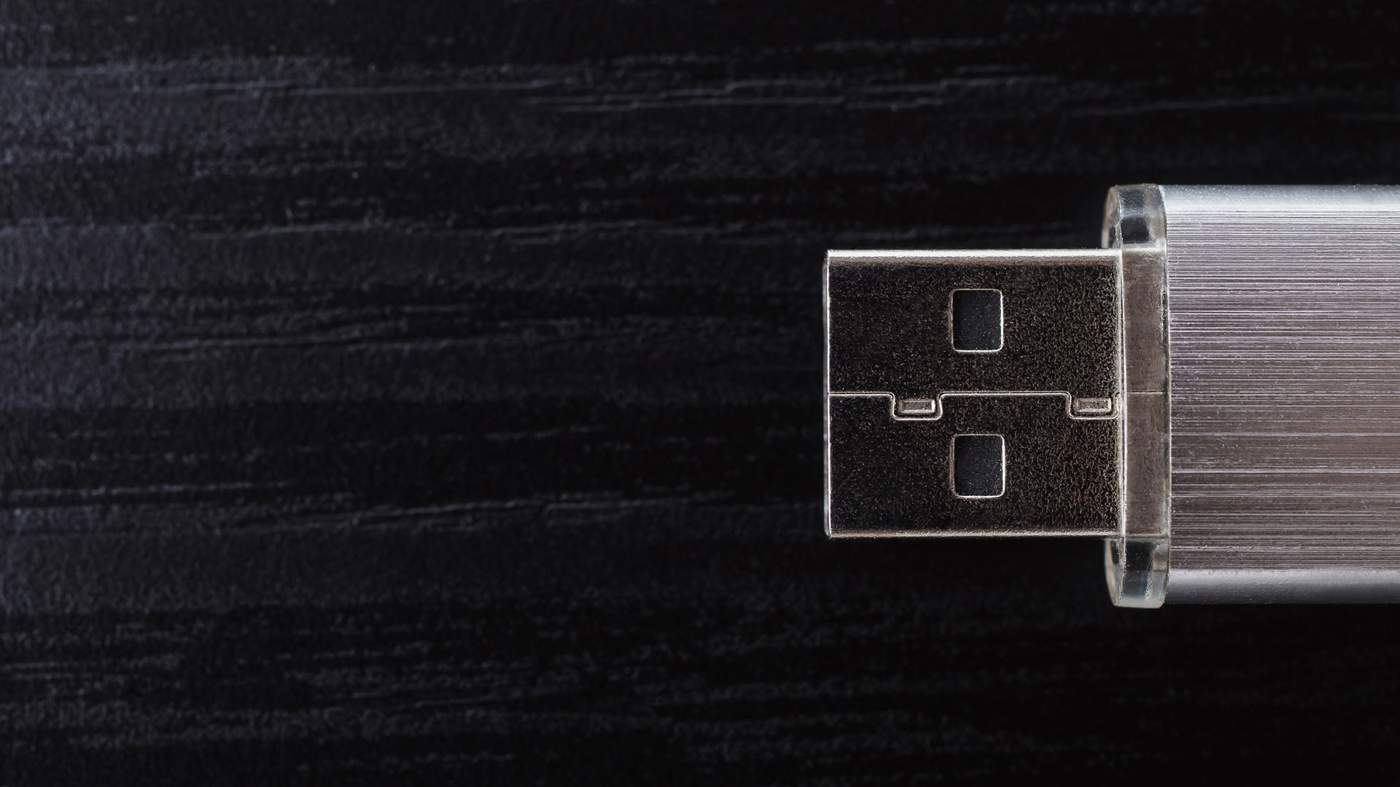

On 25 January 2014, the employee placed a USB stick into a computer at the French company. “The horse was planted this morning,” he texted the Chinese intelligence officer later that day, according to the US indictment.

The next month, the company’s computers “beaconed”, contacting a web domain controlled by Chinese hackers. That came to the attention of the US which informed French intelligence. They contacted the company, which began to investigate.

But the hackers had an advantage. Another employee - an IT worker - at the company in China was working with them, it is alleged. Text messages were exchanged with the hackers and within hours the web domain being used was deleted to cover their tracks, according to the US indictment.

The US alleges that from 2010-15 this group - led by a Chinese intelligence officer - worked with employees in China to steal sensitive data related to a turbofan engine used in commercial airliners.

None of the accused, who are all based in China, are likely to be brought to trial. The indictments are part of a strategy by the US to put information into the public domain about Chinese activity in order to put pressure on Beijing.

What is clear from both stories is that for all the talk of cyber espionage, people still matter. Individuals within companies can - knowingly or unknowingly - provide secrets. So how does Chinese intelligence identify people to target?

There has been a lot of coverage of Chinese cyber attacks but the insider threat is often more dangerous than remote hacking, US officials say.

Chinese intelligence is “prolific” at targeting people over social media sites like Linkedin, Evanina claims. “If you look at it from a perspective of the intelligence service it's a low-risk, high-yield ability to send out 30,000 or 40,000 emails and get 20, 30, 40 people respond and say, ‘I have that technology. I can come over to the presentation.’ It's a very, very successful use for them.”

A year ago the German security service warned that 10,000 Germans had been contacted by fake profiles disguised as head-hunters, consultants, think-tankers or scholars who were actually Chinese intelligence agents.

Chinese spies are believed to be targeting UK secrets - but the British government has been far less willing to speak out about it.

Those working in national security in the UK confirm privately that they see the same range of activity as in the US. But while there have been a string of indictments in America and statements from senior figures in the Trump administration, the UK government so far has been far less vocal.

US officials privately say they want the UK to take a tougher line but so far British officials have been careful.

British security officials are particularly concerned about universities being targeted for research and intellectual property.

The concern is that they are a soft target for economic espionage either through individuals being invited to China, agents arriving in the West as students and returning with intellectual property, or even potentially through exploitation of formal partnerships between the universities.

One major UK engineering company is working with a university on research on advanced materials. The university is also working with the Chinese government. The company ensures the rooms they use are regularly swept for listening devices.

The National University of Defense Technology (NUDT) in Changsha is one of China’s top universities. Run jointly by the defence ministry and the education ministry, and with close ties to the People’s Liberation Army, it has been at the leading edge of the country’s space and super-computer programme.

It also works closely with Western universities.

National University of Defense Technology, Changsha

The 91�ȱ� found a number of UK universities listed on a database as collaborating with the NUDT on a series of academic papers. Much of the collaboration appears to involve aerospace and aviation.

There is no suggestion that these collaborations involve espionage or anything untoward but the level of co-operation worries some of those who study Chinese influence.

“Collaboration between the United Kingdom and NUDT is highly concerning. UK universities are estimated to have trained hundreds of scientists from NUDT as part of the Chinese military's efforts to leverage foreign civilian expertise for military ends,” argues Alex Joske, an Australian researcher who has studied the subject. “At the moment, there appears to be little oversight of these engagements.”

But there is a scheme in place to help universities avoid risk - the (ATAS) - and it is run by the UK government.

Much of the threat, Evanina says, comes from people who are not spies per se. “They use scientists, engineers, businessmen. They can come here, ingrain themselves in the organisation, be part of a culture, work on a significant project, classified or unclassified, and be in a position to obtain that data for nefarious reasons, and send it back.”

Of course, all countries use espionage. The UK and US both carry out espionage against China and its companies.

But Western officials argue there is a difference in the way China operates. They say that China has an over-arching strategy to target commercial information specifically to support its companies, which are often linked to the state. This is something they say their spies do not do.

China denies that it is engaged in a massive programme of secret stealing.

"US actions have damaged China's rights and interests, undermined China-US mutual trust and cast a shadow over China-US relations," a Chinese Foreign Ministry official has said of recent US accusations. "We urge the US to immediately stop its misguided comments and actions."

The Trump administration is determined to push back on Chinese espionage. It has pursued a strategy in recent months of indicting Chinese individuals, like Xu.

Other indictments have alleged plots to steal technology involving semiconductor chips, , and even .

Power, money and politics is going east, that’s the political reality we need to adjust to

“I can tell you there’s more coming and there’s more out there,” says Bill Evanina. He argues that China is a greater security threat than Russia.

The concern is not just about China using espionage to achieve economic growth but also how the Chinese state increasingly uses its weight to wield influence around the world.

It is certainly the case that it is politically useful for the Trump administration to focus on China more than Russia. But if you speak to national security officials they do believe in the urgency of the threat.

The campaign to take a tough line on espionage is just part of a wider confrontation about economic power involving trade and technology. Washington wants its allies to stand alongside them in their campaign.

Australia has been at the leading edge of the debate over Chinese influence, including in politics and universities. In June it passed new counter-espionage laws which criminalise “covert, deceptive or threatening actions that are intended to interfere with democratic processes or provide intelligence to overseas governments”.

The laws are designed to include actions that might have fallen short of previous definitions of espionage.

In the UK so far there has been more caution. “Power, money and politics is going east, that’s the political reality we need to adjust to,” the chief of MI6, Alex Younger, said last month.

A government spokesman said: “We do not routinely comment on intelligence matters or the detail of any alleged threat we face. The government is alert to the array of potential threats the UK faces and takes national security extremely seriously.”

But senior officials in the UK talk about needing a nuanced approach and are wary of being caught in the middle of a damaging slugging match between Washington and Beijing. There is no doubt that if they had to choose between the Trump administration and China they would take America’s side. But they would rather not be faced with such a choice.

“We are unsure whether the rise of China is a threat or an opportunity. The truth is that it is both, but navigating that is difficult,” argues Robert Hannigan.

In Washington, while many officials believe it is vital to confront this challenge now, others fear China may already have been able to make sufficient strides forward economically to guarantee its influence globally.

Even with a crackdown under way, a few privately say that they fear it may already be too late to stop China's plan.