Mental health – “We must have change”

- Published

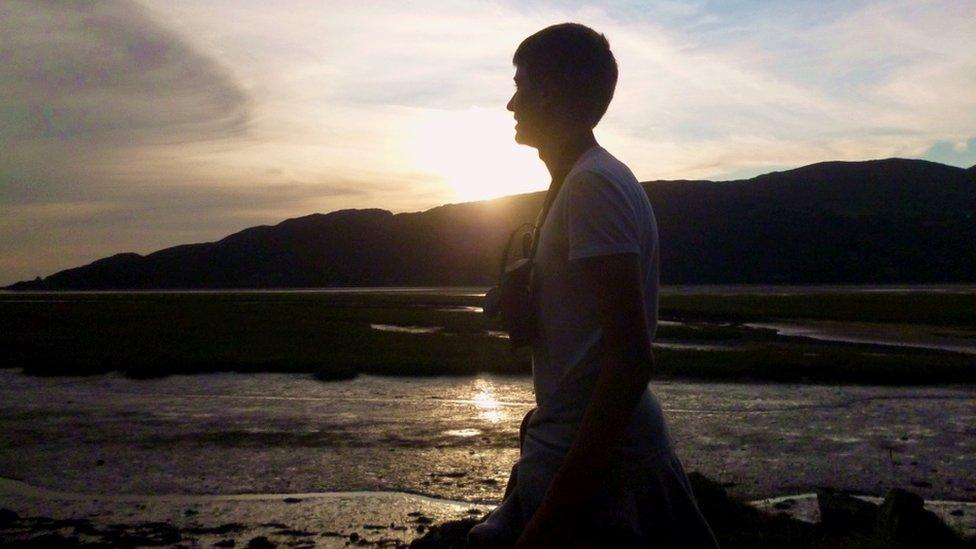

Steve Mallen set up a campaigning charity called The MindEd Trust after his son Edward's death in February 2015

Conferences of the great and the good in areas like science, health and politics take place at Oxbridge colleges most weeks of the year. But this one was like few others.

Conceived and organised by the father of an 18-year-old who had taken his own life barely a year earlier, this one-day gathering offered a broad and challenging view of the state of mental health care of young people in England.

It revealed a widely shared view that notwithstanding the recent publication of NHS England's Mental Health Taskforce report, there is a lack of drive and joined-up thinking in government and the health service.

Steve Mallen has already shared his grief and anger at the loss of his son. A talented straight A-grade student, Edward was set to go to Cambridge University. But in a matter of weeks he succumbed to depression and took his own life.

His father, who argued that Edward had been failed by the system despite seeking help, wrote a strongly worded letter to the prime minister calling for a formal review of teenage mental health.

Edward Mallen took his life aged 18 after becoming severely depressed

Steve Mallen set up a campaigning charity soon after Edward's death in February 2015 and the conference held at a Cambridge college was part of his drive to establish the nature of problems with the system and seek solutions.

He managed to get key representatives from the major political parties, officials from the main NHS organisations, academics and mental health campaigners into the same conference hall, which was no mean achievement.

Mr Mallen told the audience that parity of esteem between physical and mental health were "empty words". Highlighting financial data, he said that with 75% of psychological disorder originating before the end of higher education it was "a nonsense" that only 10% of the mental health budget was spent on young people.

Mental health literacy across society was "shocking", he said, and he felt he was standing next to his son on behalf of his generation and made a plea to the assembled experts: "We must have change."

Norman Lamb, for the Liberal Democrats, argued that there was nothing the government could do which was more important than dealing with the "awful neglect" of mental health. Labour's Luciana Berger, via a recorded video, paid tribute to Steve Mallen and said there was a journey which had to be continued.

Steve Mallen organised a conference on the mental health of young people

Francesca Reed of the Youth Select Committee, an initiative supported by the House of Commons, called for more work in schools. She said training for lunchtime supervisors as well as staff was required to enable them to help pupils who needed it.

Rosie Tressler of Student Minds noted that there was stigma associated with students with mental health challenges, including even at medical schools.

The minister with responsibility for mental health, Alistair Burt, told the conference that when he had been given the job by David Cameron he had been told to "move things on" beyond the work done under the coalition.

He said every clinical commissioning group had been told to come up with robust local plans on how money was being spent on children's and adolescent mental health services.

Mr Burt received some animated questions from the floor.

The Departments of Health and Education, it was claimed, did not work together effectively on mental health in schools. Educational pressures, including tests, were blamed for creating unnecessary stress for children. The minister said he had regular meetings on the subject with his counterpart at Education.

It was just one of many gatherings focussing on mental health. But this conference organised by one campaigner, bringing together politicians, civil servants from different parts of Whitehall, charities and those with personal and family experiences of mental illness, was unusual.

It illustrated the continuing frustration about the financing and profile of mental health care. We will certainly hear more from Steve Mallen.

- Published15 February 2016

- Published15 February 2016