Rogue protein 'may spark diabetes'

- Published

Amyloid could 'directly poison' pancreas cells

Shedding light on how a malfunctioning protein helps trigger type 2 diabetes could one day offer the chance to halt the damage, say scientists.

The presence of amyloid protein may produce a chain reaction which destroys vital insulin-producing cells.

Researchers based in Dublin, writing in the journal Nature Immunology, say future drugs could target this process.

Amyloid is implicated in many other diseases, most notably Alzheimer's.

Type 2 is the most common form of diabetes, normally developing in later adulthood.

As much as 5% of the UK population may have it, and the NHS spends an estimated 10% of its budget treating it and dealing with complications.

It happens when the body both loses the ability to produce enough insulin to control blood sugar levels, and becomes resistant to the insulin that it does have.

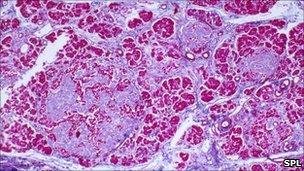

Insulin is made in "beta cells" in the pancreas, and scientists first noticed "deposits" of the amyloid protein in pancreatic tissue of some people with type 2 diabetes some years ago.

It was thought that amyloid could be poisoning the cells directly, but the latest research offers an additional explanation.

It found that a type of immune cell called a macrophage, whose normal role is to get rid of debris in the cell, reacted abnormally when it ingested amyloid.

It triggered activity in other cells nicknamed "angry macrophages", which in turn released proteins that cause inflammation.

The inflammation then destroys the vital beta cells, and the ability to produce insulin is reduced.

Interruption

The researchers said that they hoped the finding would "spur new research" to target the mechanisms of the disease.

Dr Eric Hewitt, a researcher into amyloid-related disease at Leeds University, said the paper was "interesting", and could help explain why the presence of amyloid deposits, or the process that laid them down, could be so damaging.

He said: "It suggests we are looking at a very complex disease - we know that amyloid is present in some type 2 diabetics, but not others.

"What we have is a second indirect mechanism which can lead to the destruction of beta cells, and this could be helpful when looking at other diseases which may involve amyloid, such as Alzheimer's.

"It does offer a possible opportunity to interrupt this mechanism at some point in the future and perhaps stop the disease from progressing."

- Published23 July 2010