The prisoner who escaped with

her guard

He has thought of everything.

He has cut the wires to the surveillance cameras.

He has volunteered for a longer night shift.

He has even laid out shoes for her by the back door.

Jeon had woken Kim up at midnight and taken her through the route he had planned.

He had packed two backpacks the night before, containing food and spare clothes, plus a knife and poison.

He wasn’t taking any chances, and was also taking a gun. Kim tried to persuade him to leave it behind but Jeon was adamant.

Surviving capture wasn’t an option. A show trial in North Korea and execution would almost certainly be the punishment - particularly since the guard was absconding with a prisoner.

“I knew I had only that night. If I didn’t make it that night I would be captured and killed,” says Jeon Gwang-jin, 26.

Jeon Gwang-jin

“If they stopped me, I was going to shoot them and run. If I couldn’t run, I was going to shoot myself.”

If that didn’t work he was going to stab himself with the knife and take the poison.

“Once I was prepared to die, nothing scared me,” says Jeon.

Together they jumped from a window and dashed across the detention centre’s exercise yard.

Ahead of them lay a high fence that they would have to scale, and the fear that the guards’ dogs, which they could hear barking, would give them away.

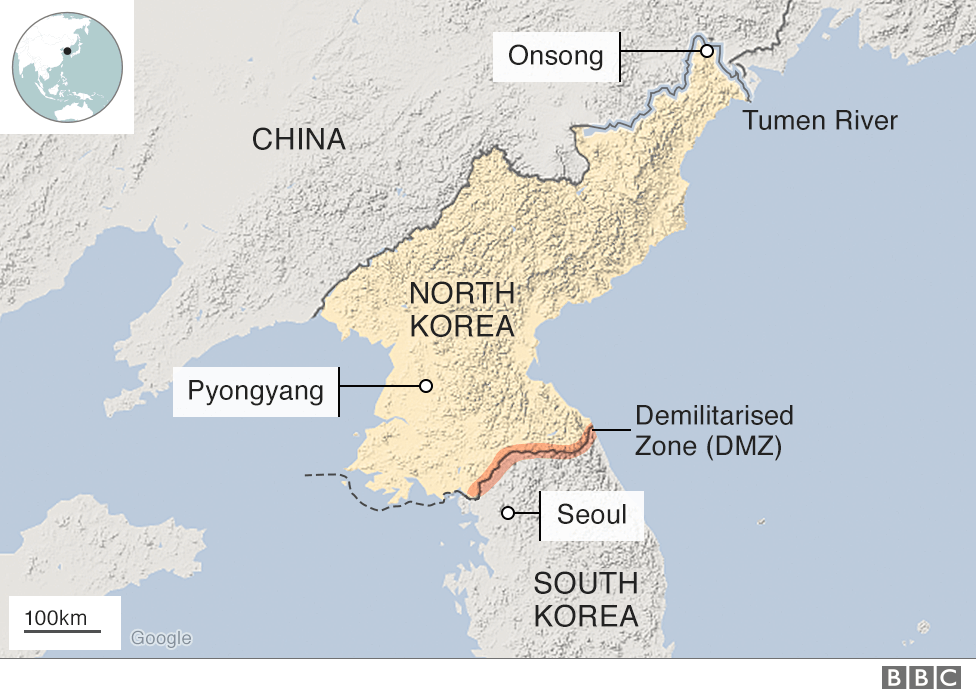

And even if no one came, if they managed to scale the fence unseen and unheard, they would need to get past the border guards patrolling the Tumen river that separated them from freedom.

But it was worth the risk.

Kim’s move from the centre to a prison camp was imminent. They both knew the appalling conditions there meant she may never make it out alive.

It was an unlikely friendship - the prison guard and the prisoner.

They had met just two months earlier - in May 2019. Jeon was one of several guards at Onsong Detention Centre in the far north of North Korea. He and his colleagues kept Kim and a few dozen other inmates under surveillance 24 hours a day whilst they awaited trial.

Kim caught his eye with her refined clothing and demeanour.

He knew she was there because of her role in helping their fellow countrymen who had already fled a life of desperation.

Kim was what was known as a broker. She helped keep channels open between those who had fled and families left behind. This could mean facilitating money transfers or phone calls from the defectors.

And it was lucrative work for the average North Korean.

Kim was paid about 30% of the cash as commission, and an average money transfer is about 2.8m won [£1,798], research suggests.

On the face of it, Kim and Jeon couldn’t have been more different.

While she made her money illicitly, learning as she did about the world outside North Korea’s strict communist regime, Jeon had spent the past 10 years in the military as a conscripted soldier. He was steeped in the communist ideology of the country's dictatorship.

What they didn’t realise was how much they had in common. Both were deeply frustrated by their lives and felt they had now run out of road.

For Kim, the turning point was her jail sentence. This wasn’t her first prison term, and she knew that as a second-time offender she would be more harshly treated this time around. If she did make it out of prison alive, then returning to a life of brokering - and potential arrest again - would have been an extremely risky thing to do.

Kim’s first arrest was for a particularly dangerous type of brokering - helping North Koreans escape over the border into China - the very route that she and Jeon would go on to take themselves.

“You can never do this line of work without connections in the military,” she says.

She would bribe them to look the other way, and was successful for six years, earning good money in the process - US$1,433-2,149 for each person she helped leave. That meant getting just one person across was the equivalent of a year’s income for the average North Korean.

But eventually the very contacts in the military who had paved the way were the ones who betrayed her.

She was sentenced to five years in prison. When she left she had intended to give up brokering. It was just too risky.

And then she made a discovery that would force her to think again.

“I told them I would pay as much as they would want me to and I begged and begged”

Her husband had remarried while she was in jail, taking their two daughters with him. She needed to find a new way to survive.

She decided that even if she did not dare help people escape any more, she could still use her contacts to do a different - slightly less risky - type of brokering. She would facilitate transfers of money from defectors in South Korea, and host illegal phone calls from them.

North Korean mobiles are blocked from making or receiving international calls, so Kim would charge a fee for receiving calls on her smuggled Chinese phone.

But she was eventually caught out again. As she took a boy from her village into the mountains to take a call from his mother, who had defected to South Korea, they were followed by the secret police.

“I told them I would pay as much as they would want me to and I begged and begged. But [the official] said because the son already knew everything they could not hide my crime and cover for me.”

In North Korea, activities which involve or suggest a relationship with an “enemy state” - South Korea, Japan or the US - can earn a North Korean a stiffer sentence than killing someone does.

Kim realised that life as she knew it was over. When she first met Jeon she was still awaiting trial, but she knew that as a second-time offender she had a tough time ahead of her.

Jeon, although not fearing for his life, was also feeling deeply frustrated.

He had begun his mandatory military service - routine tasks such as guarding a statue of North Korea’s founder and growing grass for livestock - intending to eventually become a police officer, a childhood dream.

But his father had now broken the truth to him about his future.

“My father sat me down one day and told me that realistically speaking a person of my background would never be able to make it [into that position],” he says.

Jeon’s parents, like their parents before them, are farmers.

“You need money to advance in North Korea… It’s getting worse and worse... Even the test you take to graduate from university, it’s now taken for granted that you bribe professors for good results,” says Jeon.

Farming families have been hit by a poor harvest recently

And even for those who do make it to a top college, or graduate with the highest honours, a bright future is not guaranteed unless that person has money.

“I know someone who graduated from the [prestigious] Kim Il-sung University as a top graduate, and yet has ended up selling fake meat in the market,” he says.

For much of the population, simply surviving is a struggle.

Living conditions may be better than they were in the early years of Jeon’s life, when the country was ravaged by a deadly four-year famine dubbed “The Arduous March”, but .

So having been told his ambition to become a policeman was impossible, Jeon had started thinking of another way to change his life.

It was still just the seeds of an idea when he met Kim, but as they talked, the idea took hold.

Theirs was an unusual relationship, and certainly not typical for a prisoner and a guard.

Inmates are not even allowed to look directly at the guards, Jeon says. They are “like the sky and the Earth”.

But he would beckon her over for whispered conversations through the iron bars of her cell door.

“There is a camera, but when the electricity is out often you can’t see the footage and sometimes they move the camera a bit.

“Inmates all know who’s close to whom, but the guards hold the power in prison.”

He says he took extra care of her. “I felt we connected,” he says.

“I want to help you sister. You may die at the prison camp.”

And then, about two months after they first met, their friendship took on an extra significance.

Kim was sent for trial and sentenced to four years, three months, in the feared Chongori prison camp.

She knew that she may never make it out of Chongori alive. Interviews with former detainees there have shed light on

“I was in despair… I thought about killing myself a dozen times. I cried and cried,” she says.

“When you go to kyohwaso [prison camp] you are deprived of your citizenship,” says Jeon. “You are not human anymore. You are no different from an animal.”

Chongori prison camp

One day he whispered to Kim the words that were to change their lives forever.

“I want to help you sister. You may die at the prison camp. The only way I can save you is by helping you get out of here,” he said.

But like many North Koreans, Kim had learned not to trust others. She thought it could be a trick.

“So I confronted him, saying: ‘Are you a spy?’ What do you gain from spying on me and destroying me?’ But he kept saying he wasn’t.”

Eventually Jeon told her that not only did he think she should let him help her escape to South Korea, he wanted to go with her.

It transpired that his prospects were also affected by his as a result of having relatives in South Korea - a national fracturing created by the Korean War.

But these relatives also gave him hope of a different future.

He showed her photos of his relatives that he had sneaked out of his parents’ house last time he was home. There were addresses written in tiny characters on the back.

Kim started to believe him.

But she was also very scared.

“My heart was beating like crazy,” Kim says. “Never in North Korean history have a prisoner and a guard escaped together.

On 12 July 2019, Jeon knew the moment had come. Kim’s move to the labour camp was imminent, and his boss had gone home for a night.

Under cover of darkness, they leapt through a window, scaled the perimeter fence, and crossed the rice paddies to the river.

“I kept falling and tripping,” says Kim, her body weakened by months of detention.

But they made it safely to the river bank. And then a light came on about 50 metres away. It was coming from the border garrison’s guard post.

“We thought it could be the border garrison tightening security having [already] discovered we had escaped from the detention centre,” says Jeon, “but we were hiding and watching and they were just changing guard... We could hear the guards talking as they changed shifts.

“We waited it out… After 30 minutes it went quiet.

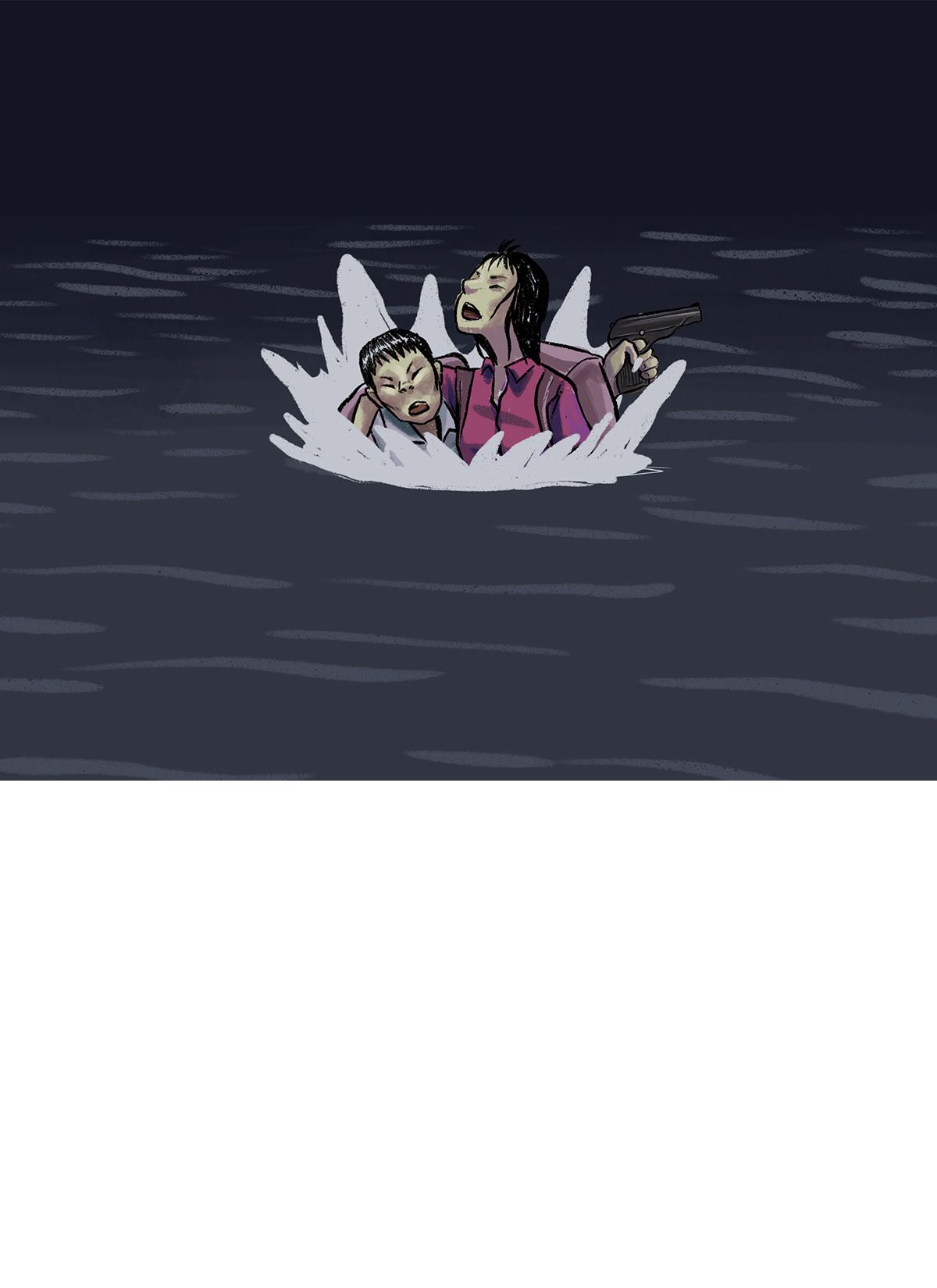

“So we went into the river. I have been to the river bank several times, and the water level has always been quite low… I never knew it could be that deep.

“If I had been on my own I would have just swum across. But I was wearing a backpack… I had a gun, and if the gun became wet it would be useless so I was holding it up with my hand. But the water got deeper and deeper.”

Jeon began to swim. But Kim didn’t know how.

Jeon gripped his gun in one hand and dragged Kim with the other.

“When we got into the middle of the river, the water was above my head,” says Kim. “I was choking and unable to open my eyes.”

She begged Jeon to go back.

“I told her: ‘We will both die if we go back. We die here, not there.’ But I was… exhausted and thinking: ‘Is this how I die, is this where it all ends?’”

Finally Jeon’s feet touched the ground.

They stumbled out and across the final bit of ground to the barbed wire that marked the border with China.

Even then they weren’t safe.

They hid in the mountains for three days until they met a local who lent them his phone. Kim called a broker she knew for help. The broker said the North Korean authorities were on high alert and had dispatched a team to arrest them, working with the Chinese police to comb the area.

But with the help of Kim’s contacts they managed to move from safehouse to safehouse until they finally made it out of China and into a third country.

Before they completed the final stage of their journeys they met us in a secret location to talk about their incredible escape and its ramifications.

“I kept falling and tripping,” says Kim, her body weakened by months of detention.

But they made it safely to the river bank. And then a light came on about 50 metres away. It was coming from the border garrison’s guard post.

“We thought it could be the border garrison tightening security having [already] discovered we had escaped from the detention centre,” says Jeon, “but we were hiding and watching and they were just changing guard... We could hear the guards talking as they changed shifts.

“We waited it out… After 30 minutes it went quiet.

“So we went into the river. I have been to the river bank several times, and the water level has always been quite low… I never knew it could be that deep.

“If I had been on my own I would have just swum across. But I was wearing a backpack… I had a gun, and if the gun became wet it would be useless so I was holding it up with my hand. But the water got deeper and deeper.”

Jeon began to swim. But Kim didn’t know how.

Jeon gripped his gun in one hand and dragged Kim with the other.

“When we got into the middle of the river, the water was above my head,” says Kim. “I was choking and unable to open my eyes.”

She begged Jeon to go back.

“I told her: ‘We will both die if we go back. We die here, not there.’ But I was… exhausted and thinking: ‘Is this how I die, is this where it all ends?’”

Finally Jeon’s feet touched the ground.

They stumbled out and across the final bit of ground to the barbed wire that marked the border with China.

Even then they weren’t safe.

They hid in the mountains for three days until they met a local who lent them his phone. Kim called a broker she knew for help. The broker said the North Korean authorities were on high alert and had dispatched a team to arrest them, working with the Chinese police to comb the area.

But with the help of Kim’s contacts they managed to move from safehouse to safehouse until they finally made it out of China and into a third country.

Before they completed the final stage of their journeys they met us in a secret location to talk about their incredible escape and its ramifications.

It is highly likely that Kim and Jeon’s actions will further damage their family's social standing within the North Korean caste system, and that their relatives will be questioned and monitored.

But both hope that their relative independence at the time - Jeon away in the military, Kim estranged from her husband and children - will allow their families to argue they did not know of their plans.

“I feel guilty that I escaped so that I could live,” says Kim. “It really breaks my heart.”

Jeon feels the same. He begins to softly hum a folk song called “Spring at 91热爆” before putting his head in his hands.

And he is sad that he is now heading for a different destination than the woman who has come so far with him. He has changed his plans and wants to go to the US, not South Korea.

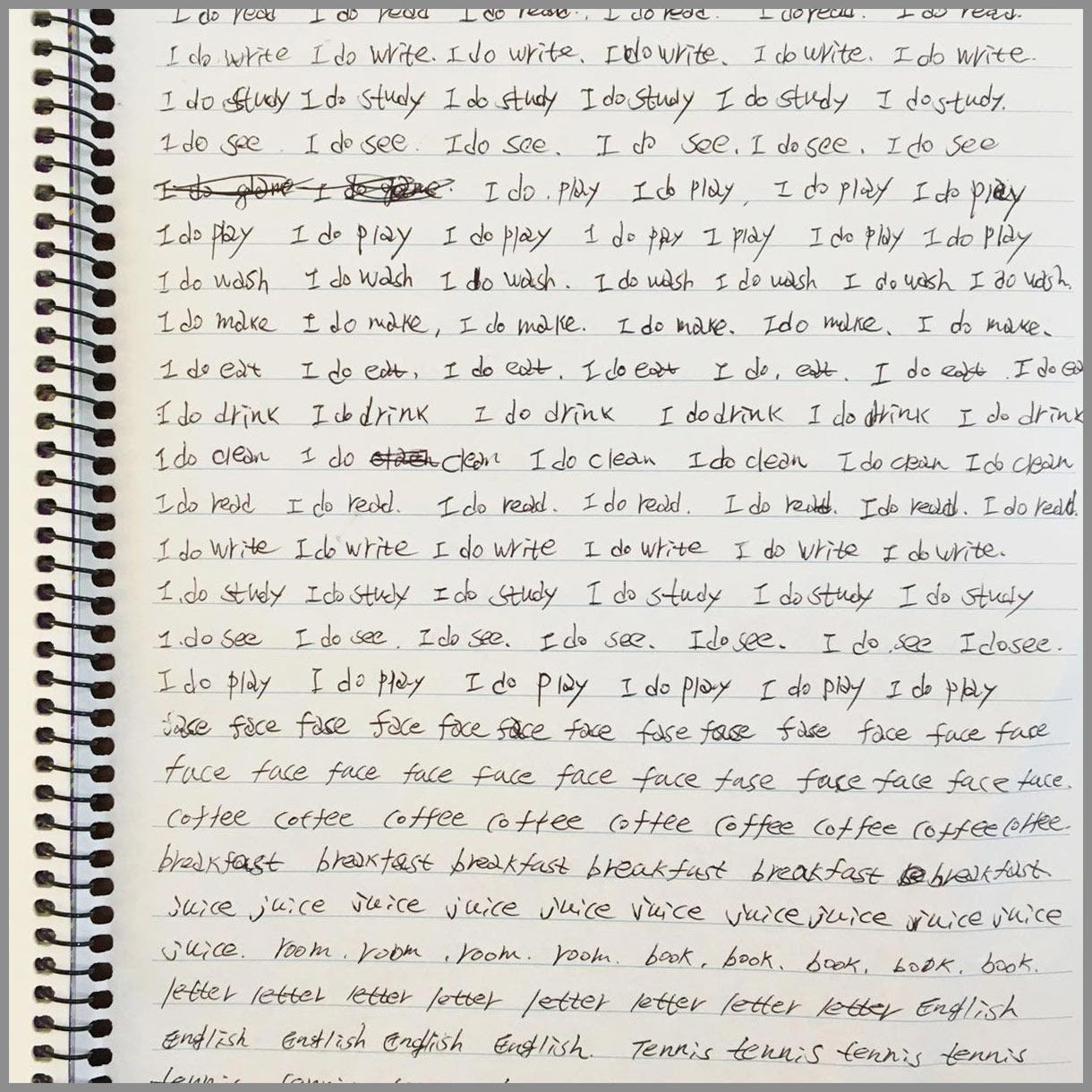

Jeon is teaching himself English while he waits to apply for asylum in the US

“Come with me to the US,” he begs Kim. She shakes her head. “I’m not confident. I don’t speak English. I’m scared.”

Jeon tries to convince her, saying they can learn English as they go along.

“Wherever you go, don’t forget me,” Kim says quietly.

But they are both glad to have left behind North Korea’s repressive regime.

“Looking back, we all lived in a prison. We were never able to go wherever we wanted, do whatever we wanted.”

“North Koreans have eyes yet cannot see; ears yet cannot hear; mouths yet cannot speak,” says Jeon.

The prisoner’s name has been changed to protect her identity in her new home.

Credits

Writer: Hyung Eun Kim

Illustrations: Davies Surya

Photos: Getty images, 91热爆

Editor: Sarah Buckley

Publication date: 21 February 2020

More long reads

The North Korean women who had to escape twice