Jon Silverman, the former 91热爆 91热爆 Affairs Correspondent (1989-2002), won the Sony Gold Award in 1996 for reports for the Today programme on the UK’s criminal investigations in the 1990s into Nazi collaborators who sought refuge in Britain after World War 2. Now, he has co-written a book on the subject, due to be published this month by Oxford University Press.

Sometimes, the seed of an idea can take an age to germinate. In 1998, a lawyer who had represented the first person in Britain to be charged under the 1991 War Crimes Act, asked me if I was interested in taking possession of nearly 50 boxes of documents relating to the case. Many were either in German or Russian. They included copies of field reports of massacres compiled by the Nazi occupiers of Belorussia after 1941 and of interrogations by an NKVD war crimes commission searching for evidence against collaborators. Others, in English, were transcripts of police interviews conducted in the 1990s with suspects living in the UK. A small handful bore the tell-tale heading Box 500, indicating that they had originated with M15 in the immediate post-war period. Others were from 91热爆 Office officials asked to rule on whether this or that Eastern European immigrant should be investigated for pro-Nazi links.

Why did the lawyer offer me this treasure trove? Well, as 91热爆 Affairs Correspondent, I had become the 91热爆’s go-to authority on Scotland Yard’s Nazi war crimes inquiries and had done a number of investigations for radio and television, earning a Sony Gold award for reports on Today in 1996. The broadcasts included a confrontation with a man called Anthony (Andrzej) Sawoniuk who had threatened me with an iron bar and subsequently earned the distinction of being the only person to be convicted under the War Crimes Act. But despite my interest, I realised that I had neither the time nor resources to undertake the task of turning my inherited archive into a book worthy of the source material.

Fast forward to 2019, nearly two decades ‘retired’ from the 91热爆 and working as a university professor, I was asked to be the external examiner for a thesis written by a former Metropolitan police detective, Robert Sherwood. The dissertation was on Britain’s war crimes team post-1945 and in the 1990s. His supervisor, a distinguished historian, Dan Stone, suggested that we should collaborate on a book proposal and here we are, four years on, being published by no less an imprint than Oxford University Press.

Any OUP publication has to be rigorously researched to withstand academic peer review, but I approached this in a journalistic mindset, keen to reveal a story which had not been told because of the obsessive secrecy of British institutions, notably Scotland Yard, the 91热爆 Office, the Crown Prosecution Service and the Crown Office in Scotland.

A number of questions had nagged away at me since the late nineties: why was there only one conviction out of dozens of cases examined in depth? What appalling crimes had some of those not prosecuted been accused of? What did investigators and lawyers in other countries, which had grappled with the same issues, think of the British record in addressing serious allegations of murder committed during the war by Nazi collaborators?

At this point, it’s important to define terms. Some of the ‘collaborators’ had willingly joined police auxiliary units, known as schutzmannschaften, in countries such as Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus and Ukraine after the German invasion, codenamed Operation Barbarossa, in June 1941. Others were part of battalions and special squads which played a vital role in fulfilling the Nazi mission to make Eastern Europe judenrein, Jew-free. They worked closely with the Einsatzgruppen which, by late autumn 1941, had already murdered more than half a million Jews in what has been called the ‘Holocaust by bullets.’ The police units were the Nazis’ eyes and ears. They had the local knowledge to identify their Jewish neighbours, helping to hunt down those who somehow escaped an aktion and provided cordons when Jews were marched from their homes to isolated forest clearings to be slaughtered. Hundreds of these men made their way to the UK after the war, many claiming to be Poles, and lived free from suspicion until the War Crimes Act was passed.

One prime suspect was a Latvian, Harijs Svikeris, who lived in Milton Keynes. He had been a platoon captain in a notorious outfit called the Arãjs Kommando, established in 1941 with the sole purpose of ridding the homeland of Jews and Communists. In that, it was highly successful and some of the documents in my archive contained graphic accounts by fellow members of the Kommando, later interrogated by the NKVD, of the active role played by Svikeris in killing missions. In the mid-1990s, the former head of Scotland Yard’s War Crimes Unit told me that he regularly asked the Crown Prosecution Service to charge Svikeris. But he was not prosecuted, on the grounds that reliable eyewitnesses to the murders he had committed could not be persuaded to testify in open court.

A Scottish case which garnered much attention concerned Anthony (Antanas) Gecas, a Lithuanian living in Edinburgh, who was described by a High Court judge as a ‘war criminal’ when he brought an unsuccessful libel action against Scottish Television. Gecas, too, despite his well-documented participation in massacres in Belorussia, escaped justice for the same reason as Svikeris. Our book describes the furious reaction of the American war crimes investigators, who had first tracked down Gecas in 1982, to the failure of the Scottish Crown Office to charge him.

The book is not a polemic. We are not arguing that these men should have been prosecuted in an English or Scottish court of law in the 1990s, though, undoubtedly, justice demanded that they should have been held to account years earlier for their crimes. But what should irk any journalist is the blanket of secrecy thrown over the war crimes process in the UK by the institutions mentioned earlier. It was understandable while the police investigations were going on, but barely forgivable that, unlike the authorities in other jurisdictions, neither Scotland Yard nor the 91热爆 Office saw fit to publish any end-of-inquiry report, barring access to the files until 2034. After all, this was a landmark process, the largest ‘cold case’ inquiry ever conducted in Britain into the most horrific crime of the 20th century and yet it has passed into history with no public scrutiny or awareness.

The lawyer who handed me his trove of documents represented a man called Szymon Serafinowicz who was charged in 1995 but never stood trial because he had Alzheimer’s. If there is any justice to be found, I like to think it rests with the demise of the aforementioned Harijs Svikeris. He died in 1995, having suffered a heart attack at his home in Milton Keynes. It was reported that he was found clutching a newspaper open at a page which carried the headline ‘First man to be charged with Nazi war crimes arrested in Surrey’.

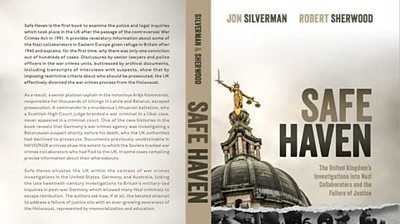

*Safe Haven: the United Kingdom’s investigations into Nazi collaborators and the failure of Justice by Jon Silverman and Robert Sherwood is published by Oxford University Press.