When the 91�ȱ� restarted Television after the war, the line standard used 405 lines to make up a picture and this was repeated 50 times a second, giving a field rate of 50Hz. This was to make it similar to the frequency of the mains supply so that any interference was stationary on the screen. Indeed, before the requirements of colour television and 625 lines, the pictures at Television Centre were ‘locked’ to the mains.

When the USA started their service, they added more lines to make 525 and ran at 60Hz to match their electricity supply. The rest of Europe also added lines to make 625, but ran at 50Hz – the same as the UK. (The French had 819 lines – they would wouldn’t they – but it didn’t last long or extend much beyond France.) So, with the inevitable rule of three systems, the question was how to mix and match pictures?

Traditionally one could point a camera on the output system at a suitable display screen, an optical system. Not too good for quality, and an electronic fudge was necessary to overcome the 10Hz flicker between 50 and 60Hz systems.

NTSC, SECAM and PAL

Then came the colour systems. The Americans used NTSC, the French used SECAM and most of the rest of Europe including the UK used PAL. Optical systems would be pretty poor here.

The 91�ȱ�, with the advantage of its world-class Research and Designs Departments, set about getting an all-electronic solution. Designs Department was charged with inventing a simpler system to work quickly, which they did and it worked well. The disadvantage was that in one direction the pictures were cropped, and in the other they were shrunk with a border.

Research Department was charged with making the ultimate solution. The difficulty lay in delaying the signals to interpolate between fields. Trivially easy in a digital world, but these were analogue days. The implausible solution was to send the signal around a faceted quartz block as a vibration – sound if you like. So instead of travelling at the speed of light, it travelled at the speed of sound – more or less.

Unbelievably it worked, provided that the quartz was kept in a very accurately temperature-controlled oven.

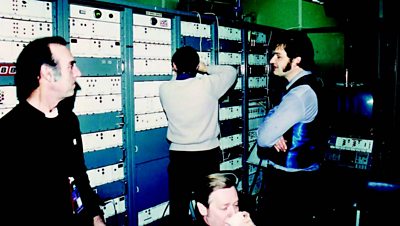

So there you have it – a behemoth monster occupying eight equipment bays. The first machine called RD1 would convert American to European, the second, RD2 (commissioned just in time for the investiture of Prince Charles), would export pictures to the USA.

Along came Pye, a British equipment manufacturer who had experience of making the line standard convertors to feed the 405 transmitters from the new 91�ȱ�1 625-line service. They made a convertor clone, which was reversible and could convert in both directions. We called that FS3 (Field Store) and changed RD1 & 2 to FS1 & 2 – all installed on the 5th floor at Television Centre.

Winter Olympics launch colour TV

The next year, 1976, the Winter Olympics were in Innsbrück, and it was a big launch of colour TV.

The European broadcasters were stretched to provide a pool of colour cameras; bear in mind, in those days, the cost of a colour camera was about the same as a modest house. There would not be enough cameras to cover the downhill ski run without losing sight of the skiers.

The American broadcaster ABC had the American Olympic rights, and they were exceptionally keen on the downhill run in which they expected to do well. Along came Roone Arledge, president of ABC Sports, with a solution.

They would ship over some US OB trucks (or scanners as we in the 91�ȱ� called them) to fill the gaps in coverage. Snag was, they only worked on the US standard.

So, he negotiated a hire of FS3 with Norman Taylor, Head of Television Network. It would work in both directions to feed their pictures into the European coverage, and to take European pictures to feed back to the States.

No pressure then; us engineers had to make it work. Ralph Barrett was put in charge of the admin and logistics, and local staff led by myself and Bryan Jones would do the difficult stuff. One problem was that a specialist computer removal firm was employed to ship it, but the convertor could only be loaded one bay at a time. Bryan undertook the task of splitting the bays and re-joining all the video cables using dozens of connectors and BNC panels. I had to reorganise the mains distribution and control cables. However, it stayed working when we put it back together each day.

Over the Alps

So, the day came when FS3 was carefully loaded, one bay at a time, into the truck and disappeared to set off over the Alps.

A day or so later Bryan and I flew to Austria (via Munich in those days, as Innsbrück airport was considered too dangerous in the winter!). The International Broadcasting Centre (IBC) for the Olympics had been created in a brand-new tram depot that had not yet been commissioned. We could see rails under the temporary floor.

Our truck arrived and the bays were unloaded and put into place. Then, horror of horrors, the bays were suddenly swimming in condensation. The four-day trek across the Alps had left them several degrees below. Nothing for it; walk away and drink some more gluhwein in the Alpen Motel.

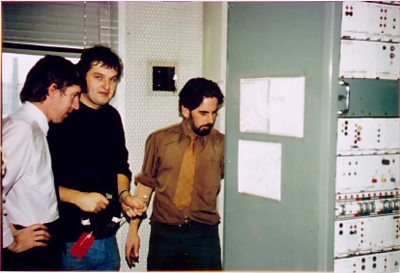

The next day, after a night in the warm, things looked better. We reconnected everything and very cautiously powered it up and waited for the ovens to reach operating temperature for the quartz delays.

Put a test signal in and… nothing.

Some frantic fault finding revealed a faulty modulator – incredibly, the only unit for which no spare existed. Close examination revealed an inductor, which had broken away from the circuit board in transit, but worse still the wire had snapped off inside the windings. The only workbench available was a music/caption stand we had brought to put the manuals on if necessary. I set myself up with a bright light and soldering iron and tweezers, and just managed to tease a turn of wire out to re-make a connection. Fraction of a turn out with the core to make up for the lost turn and fingers crossed. Pictures! Phew, there was a lot riding on this.

Lost in translation

It was a new experience for us working with an American Master Control. We tried to avoid the ‘all video go bud’ culture and use very British terminology; they would insist on calling it a scan convertor. I had a little Union Jack badge on my bright turquoise ABC jacket.

They had organised on-air cues, which we connected to the red on-air transmission light (‘tally light’ to them).

Next, more of our team arrived: Pete Nash and Dave Lawton. They were followed a little later by Andy Davies and Arthur Crews.

During our stay we had explored a bit, using the narrow-gauge railways leading up the ski slopes and the bobsleigh run. So we took the new recruits on a short sightseeing trip in the evening. Unfortunately, getting off the train, Andy slipped on the ice and had obviously broken something. Sadly he had to fly back the next day to be by replaced Chris Cooper.

One night, which because of the time difference was the busy time for transferring material to the States, the ABC videotape reported the convertor output unrecordable. Fortunately, Dave Lawton was able to locate and adjust out the offending waveform spike. After that, things went fairly smoothly; the high-key alpine pictures looked great even after conversion and ABC were very pleased with the operation. It’s the only time in 42 years at the 91�ȱ�, with eight years as freelance to make the round 50, that I have ever had my name on a roller caption.

At the end we dismantled it all and it was shipped back to its home at Television Centre. No condensation on this trip, and it carried on working for some years, only to be replaced by units occupying less than a quarter of a bay, and later with the advent of digital television, modules less than the size of a large bar of chocolate.

Since 1976 I have been seconded to the EBU and worked on every Winter and Summer Olympic Games from 1996 to 2012, but as they say, you always remember your first.