There are some tastes and textures we humans just can’t seem to agree on.

Hand someone a slab of chocolate or a slice of hot buttered toast and it’s unlikely (but not impossible), you’ll get a barely disguised look of disgust. On the other hand, offer up something more divisive, such as a piece of licorice or something smothered in desiccated coconut and chances are you’ll get more people declining a nibble.

It shouldn’t make sense. We all breathe the same air to survive, absorb rays from the same sun and have one of eight blood groups pumping through our bodies, so surely we should welcome the same fuel, whatever flavour it may be?

But we don’t. And it’s not just because we’re a fickle bunch. Taste is a serious science and to get a greater understanding of it, you might want to take a closer look at your tongue.

Things that go bump on the palate

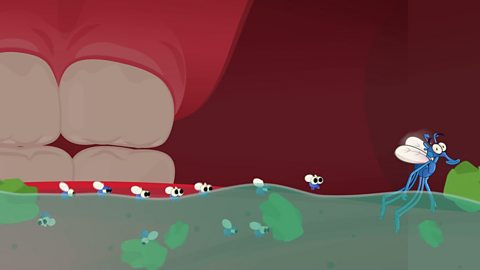

We all have bumps on our tongue. They’re called papillae and they’re the usual home of our taste buds, which react to the different flavours in food when they reach our mouth. However, the amount of papillae on our tongue varies from person to person.

Those flavours fall into five categories: bitter, sweet, sour, salty and umami (or, savoury). But with the amount of flavour receptors in our taste buds varying from person to person, it means we will all have different reactions to the same food.

That’s especially true for super tasters. They have more papillae on their tongues and it means certain flavours, particularly sour or bitter ones, can be overwhelming, which means they tend to stick to the milder dishes on the menu.

On the other hand, those with fewer papillae than average aren’t anywhere near as sensitive to strong flavours and are known as subtasters. If eating a particularly fiery curry doesn’t have you breaking out in a sweat you’re likely to be a subtaster, whereas a supertaster would have to dilute the dish with yogurt or cream first to make it palatable.

Want to check if you’re a super taster? The best way is to dab some blue food colouring on your tongue. Blue dye won’t stick to papillae, so if your tongue doesn’t go very blue, it means you have more of the papillae that makes people super tasters.

Love beans? Could be your genes

Taste buds are only the beginning. There are so many different chemicals involved when it comes to the five tastes that a lot of it depends on how our brain reads the signals sent from our tongue.

From birth, we inherently understand that sweet is good and bitter is not. It’s a survival technique because things that can do our insides harm don’t tend to taste very nice.

While that is evolutionary, our genetics play a part too. We have around 25 receptors on our tongue that detect bitterness but they don’t work the same way for everyone. One in particular, snappily called TAS2R38, is concerned with our ability to detect a flavour known as propylthiouracil, or PROP for short. Not everyone can taste PROP and further studies has shown that, if you can’t, you’re more likely to enjoy chilli and eat more fatty foods.

While we’re in the womb, we also get used to enjoying the same food that mum does. The flavour is passed through the amniotic fluid into the womb and also through breast milk after birth. After that, however, it’s how much exposure we get to different flavours which influences our list of enjoyable foods.

Elizabeth Phillips, a psychologist at Arizone State University is an expert in taste. She said: “Up until the age of two you will eat anything.

“But then you become neophobic, that is, you don't like new food. So if you hadn't already been exposed to a certain flavour by the time you hit your terrible twos, whether through amniotic fluid, breast milk or solid food, chances are you won't like it.”

Some tastes are growers

Your eighteenth birthday is potentially a wondrous day of taste exploration. It could be the very first time you try beer. And if you taste beer for the first time and love it, you’re a rarity as humans are predisposed to react against such a bitter flavour.

But the beer industry isn’t failing so, clearly, somebody likes the stuff. This is a case of where anyone who dislikes a food on first taste, can train themselves to enjoy its flavour over time.

Dana Small, a professor of psychiatry and psychology at America’s Yale University, said in a 2013 study: “When you ingest something, all these hormones are released. Your blood glucose changes, you’ve all these metabolic effects that are critical for changing the brain’s representation of flavour. If you experience a novel flavour and experience positive post-ingestive effects, then the next time you ingest that flavour you’ll find it better and will be more likely to eat [or drink] more of it.”

But the reverse is also true. As Dr Phillips points out, if eating or drinking something for the first time makes you ill, your body’s survival mechanism will kick in. This make you develop an aversion to it as your brain associates it both the smell and taste with being poisoned.

The mystery of texture

Although evolution, culture, gender and life experience provide clues to why different people react to different flavours, the one enigma that can’t be explained is our individual reactions to texture.

While some of us enjoy nothing more then chewing on a bit of bacon gristle, others are repulsed and spit it straight out into a hankie. The mouth-feel of certain foods can be enough to put some people off (for example, baked beans or coconut) but scientists are as yet unable to come up with a satisfactory reason why. All they do know for sure is that if you can’t stand lumpy custard, you really won’t go anywhere near it.

This article was published in June 2019

How do humans digest food? video

Find out what our human body does with the food that we eat

What is dietary fibre? video

Dietary fibre is found in food. Find out about its important role in digestion in this Bitesize science video for KS3.

Veggie before it was cool

Four famous people in history you didn’t know were vegetarian.